Quote: “We must sell the ‘religion of democracy’”– First Unofficial Voice of America Mission Statement By Nelson Poynter, Office Of The Coordinator of Information

[mks_pullquote align=”left” width=”600″ size=”24″ bg_color=”#dd9933″ txt_color=”#ffffff”]There is a crying need to invent a new technique in international propaganda broadcasting. The ordinary American commercial program is not the answer. We are fighting a religious fanatical crusade. In turn, we must sell the “religion of democracy”. It is a different, tougher assignment than to sell a cereal or a toothpaste. Houseman has been recommended as the man who has the professional craftsmanship, the imagination, and the personality to do this.[/mks_pullquote]

— Nelson Poynter, U.S. Office of the Coordinator of Information, January 11, 1942

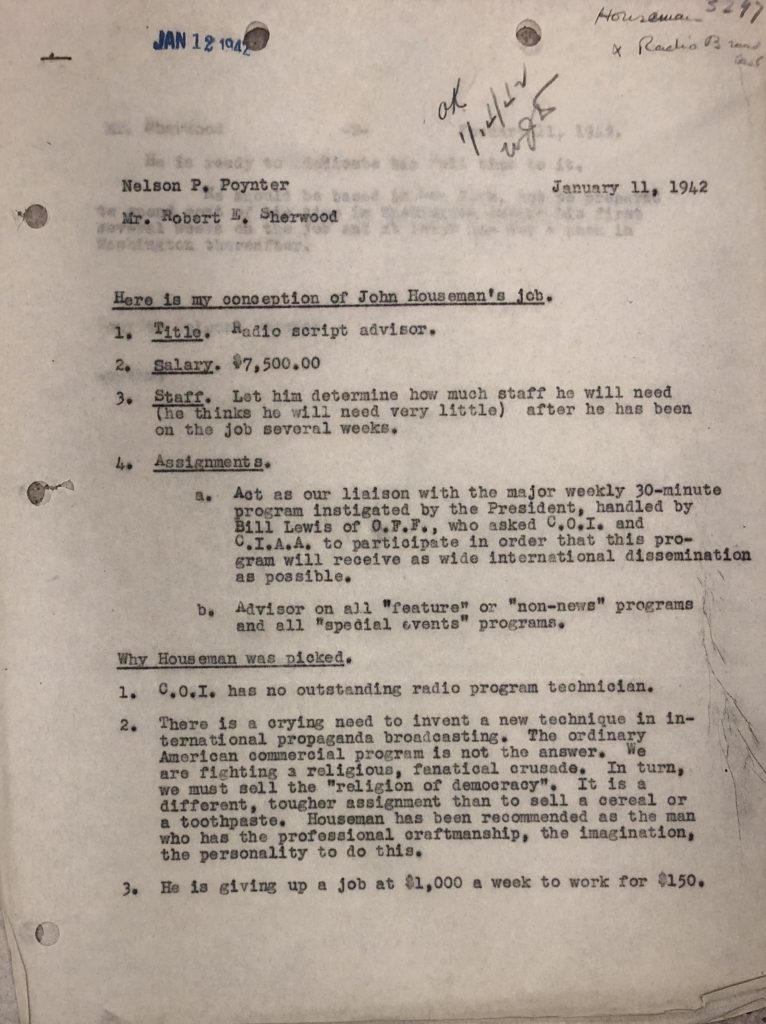

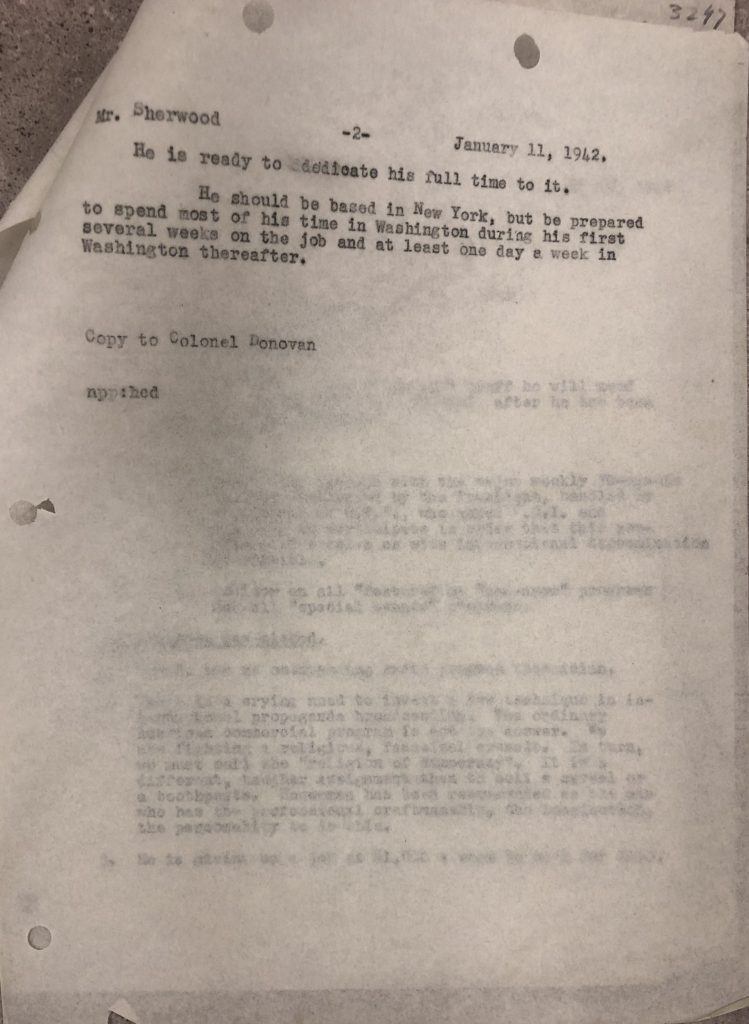

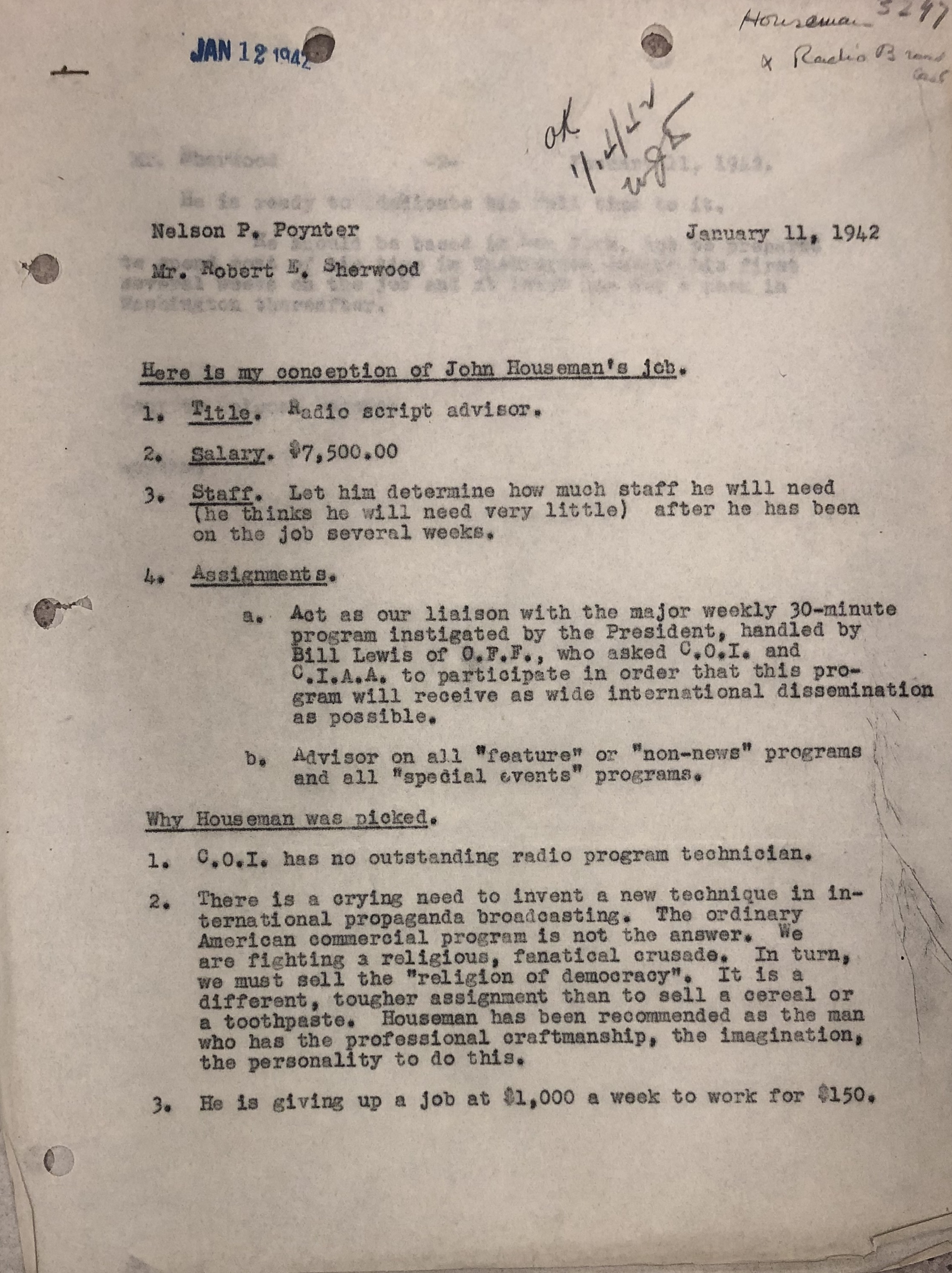

“To sell the religion of democracy” is believed to be the first written though unofficial mission statement describing the purpose of the Voice of America (VOA) radio broadcasts for overseas audiences as they were being planned during World War II in the U.S. government Office of the Coordinator of Information (COI). These words were written on January 11, 1942 not by a conservative anti-communist, but by a progressive American media publisher, Nelson Poynter. In a government memorandum, he was justifying the hiring of John Houseman to become VOA’s first director, although the Voice of America name would not be officially adopted for several years, and Houseman was the chief radio producer rather than the program director. Robert E. Sherwood and Joseph F. Barnes were responsible for the content of the new U.S. government’s shortwave radio broadcasts. Houseman was hired from his job in Hollywood, and the first Voice of America German broadcast aired in February 1942.

VOA’s main mission was to produce psychological warfare broadcasts against Nazi Germany and Japan. But under Houseman and many communist and pro-Soviet broadcasters he hired after getting his federal job, the U.S. government station soon acquired the reputation as a propaganda arm of Soviet Russia and an apologist for its communist leader Joseph Stalin.

VOA began to counter Nazi propaganda, but Houseman and his team also started to sell the Soviet dictator and mass murderer as a democratic leader. Soviet Russia was then America’s war ally. But besides praising the bravery of Soviet soldiers, the Voice of America fully absorbed Soviet propaganda for the duration of the war. It presented Stalin as a responsible statesman who would secure peace and justice in countries of post-war East-Central Europe.

During World War II, Nelson Poynter worked for the Roosevelt administration as a high-level official in charge of several U.S. government international and domestic propaganda and domestic war censorship programs. In his private career, Poynter was the owner of the Times Publishing Company, and the co-founder of the Congressional Quarterly. In his later private professional career, he established the Modern Media Institute, which was renamed the Poynter Institute after his death in 1978 and functions today as a school of objective journalism.

A Wikipedia article about Nelson Poynter does not mention his wartime U.S. government jobs, which included being the chief of the Motion Picture Industry Liaison Division in the Office of War Information (OWI). He coordinated with Hollywood studios the production of various wartime films, including the most blatant pro-Soviet propaganda film of the time, Mission to Moscow (1943). The film presented the Soviet dictator as “an omniscient world statesman.” The infamous Great Purge of the 1930s, in which hundreds of thousands of innocent people were executed, was dismissed as “necessary measures to root out a fifth column.”[ref]Clayton R. Koppes, “Regulating the Screen: The Office of War Information and the Production Code Administration,” ENCYCLOPEDIA.com. Accessed January 16, 2020. https://www.encyclopedia.com/arts/culture-magazines/regulating-screen-office-war-information-and-production-code-administration.[/ref] Aware of public opinion surveys showing a strong distrust of Russia among ordinary Americans even after the Soviets became America’s war allies against Germany, Nelson Poynter of the OWI’s Bureau of Motion Pictures advised Hollywood filmmakers “to silence doubters.” He was pleased that a draft screenplay for Mission to Moscow demonstrated how “Russians are an honest people trying to do an honest job with about the same total objectives as the people of the United States.”[ref]M. Todd Bennett, One World, Big Screen: Hollywood, the Allies, and World War II (University of North Carolina Press, 2012), 176.[/ref]

While these films were OWI-coordinated domestic propaganda aimed at Americans, foreign audiences were equally deceived by Voice of America broadcasts produced by pro-Soviet journalists and broadcasters under Houseman’s watch. Some were members of various communist parties, but most were leftist idealists, activist journalists, and naïve fellow travelers. As a result of massive complaints about the Office of War Information and Voice of America broadcasts, the U.S. Congress voted in 1943 to eliminate almost the entire OWI’s domestic propaganda budget and nearly defunded Voice of American overseas radio operations.

When Nelson Poynter wrote his memo on January 11, 1942 to Robert E. Sherwood, another Coordinator of Information government executive and speechwriter for President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Voice of America broadcasts had not yet started, and the Voice of America name was not to be officially used for quite some time to describe them. According to Poynter, their creation and hiring of John Houseman were critically necessary because the United States was already engaged in “fighting a religious, fanatical crusade [sic].” Houseman may have been seen as the best candidate for the job not because of any journalistic skills, which he lacked, but because of the powerful propaganda impact of the 1938 fake news The War of the Worlds radio program, which he co-produced with Orson Welles.

”There is a crying need to invent a new technique in international propaganda broadcasting. The ordinary American commercial program is not the answer. We are fighting a religious fanatical crusade. In turn, we must sell the “religion of democracy”. It is a different, tougher assignment than to sell a cereal or a toothpaste. Houseman has been recommended as the man who has the professional craftsmanship, the imagination, and the personality to do this.”

Nelson Poynter, U.S. Office of the Coordinator of Information, January 11, 1942

There is a crying need to invent a new technique in international propaganda broadcasting. The ordinary American commercial program is not the answer. We are fighting a religious fanatical crusade. In turn, we must sell the “religion of democracy”. It is a different, tougher assignment than to sell a cereal or a toothpaste. Houseman has been recommended as the man who has the professional craftsmanship, the imagination, and the personality to do this.

Nelson Poynter addressed his memorandum to Robert E. Sherwood, a noted Hollywood playwright, COI co-director, and speechwriter for President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Poynter later worked in the COI’s successor agency, the Office of War Information, where Houseman produced VOA radio broadcasts until his forced resignation in mid-1943. At OWI, Poynter continued to coordinate with Hollywood studios the production of pro-Soviet and other war propaganda films, and later returned to his private newspaper publishing career.

“Psychological warfare could not furnish me with the theater’s climaxes…; there was no applause for the Voice of America…”

John Houseman, Unfinished Business (New York: Applause, 1989), 247.

Born Jack Davies Houssemann, John Houseman has been presented for decades as the first director of the Voice of America. He was hired on April 1, 1942, as Chief of Radio Production for the United States Coordinator of Information. His title changed later to Chief of Radio Program Bureau in the Overseas Operations Branch of the newly created Office of War Information. In his 1902-1988 memoirs Unfinished Business, Houseman confirmed that even after covert operations were moved to the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the Office of War Information continued its psychological warfare operations under his boss and President Roosevelt’s speechwriter Robert E. Sherwood.[ref]John Houseman, Unfinished Business — Memoirs: 1902-1988 (New York: Applause Theatre Book Publishers, 1989), 248.[/ref]

He added, however, that Sherwood believed that “truth … is by far … most effective form of propaganda.”[ref]John Houseman, Unfinished Business — Memoirs: 1902-1988 (New York: Applause Theatre Book Publishers, 1989), 245.[/ref]

The Voice of America has continuously presented only this part of Houseman’s biography as part of VOA’s official history. The VOA management has consistently obscured one fact. John Houseman and scores of early Voice of America journalists including communists and other apologists for Stalin were duped by Soviet propaganda and promoted it in VOA radio broadcasts during World War II and even to a smaller degree for a few years after the war.

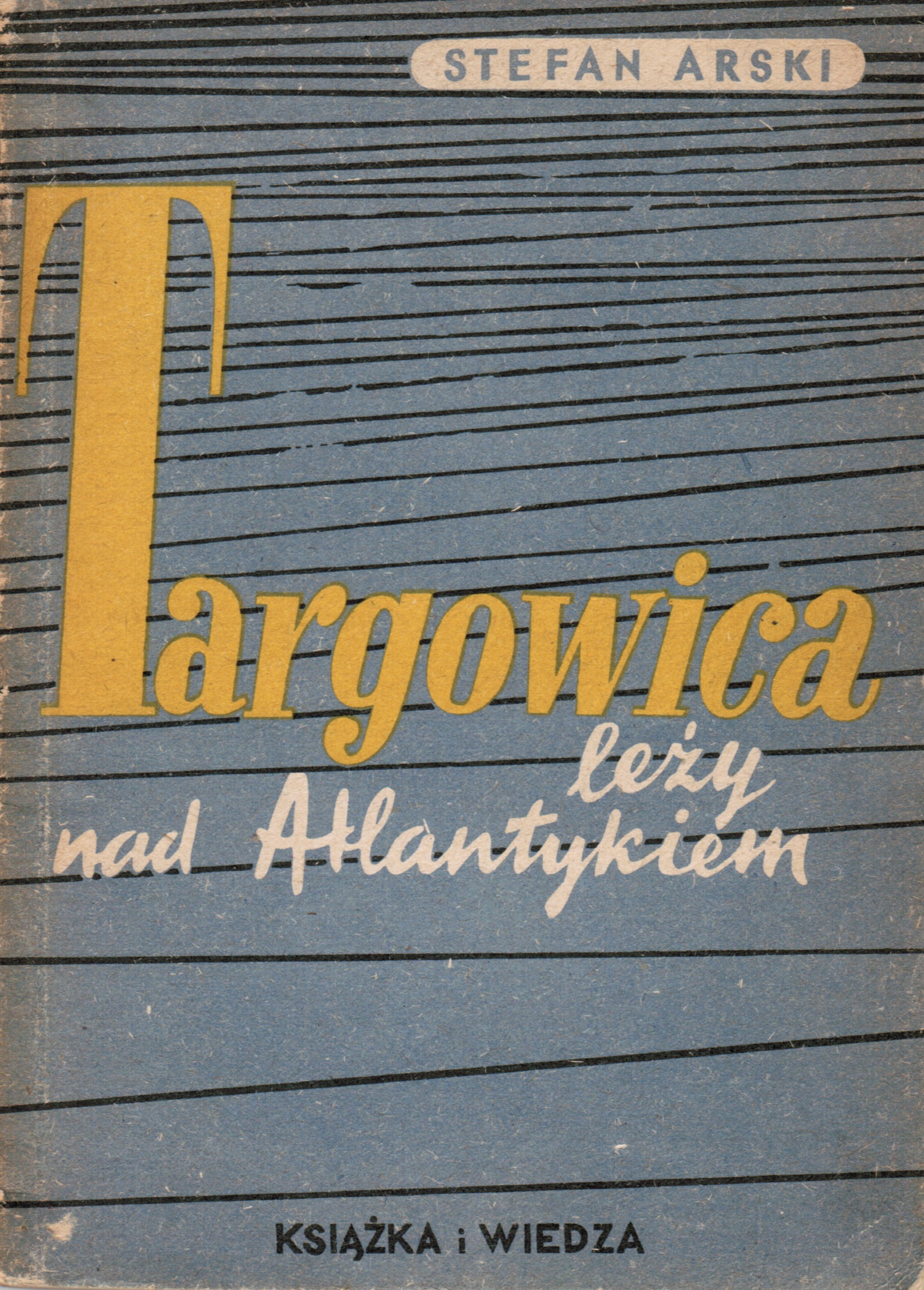

During World War II, the “Voice of America” name was then not yet officially used for shortwave radio broadcasts produced under Houseman’s supervision. Still, some of VOA’s pro-Russian socialist and communist propagandists referred to their radio broadcasts in printed materials as “Voice of America” already in 1943. Some of them, including Stefan Arski, aka Artur Salman, worked later as propagandists for pro-Soviet communist regimes in East-Central Europe. Arski returned to Poland and joined the Communist Party. The chief of the wartime Voice of America Czech Service Adolf Hoffmeister returned to Czechoslovakia and became the regime’s ambassador to France.[ref]Unconquered Poland. (New York: Poland Fights: “Polish Labor Group,” 1943).[/ref]

“And the United States? This promised land of many miracles described to radio listeners in Voice of America programs. If one could eat words, one would die from overeating. Meanwhile, [Polish immigrants in the U.S.] are dying from hunger, just as they are dying in Canada.”

Stefan Arski, aka Artur Salman, a former wartime Voice of America (VOA) socialist writer and editor (until 1947) wrote such anti-U.S. propaganda in his book published in 1952 by the communist regime in Poland. Targowica leży and Atlantykiem (“Transatlantic Traitors”), (Warsaw: Książka i Wiedza, 1952), 102.

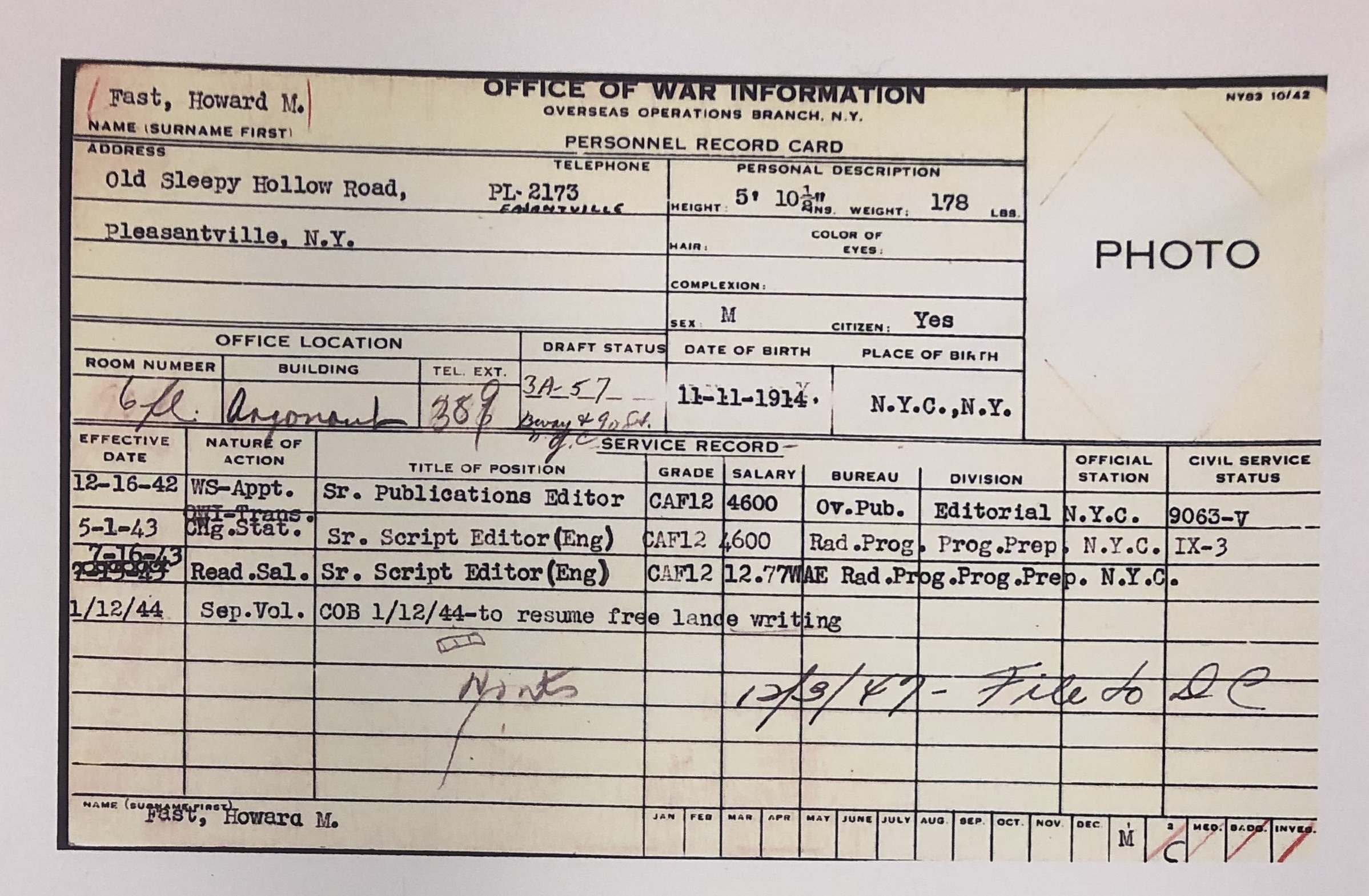

In early 1943, Houseman recruited Howard Fast, a future Communist Party USA member, and the 1953 Stalin International Peace Prize winner, to be the chief writer and editor of Voice of America radio news.[ref]Ted Lipien, “Howard Fast – Voice of America’s Only Stalin Peace Prize Recipient,” Cold War Radio Museum, March 12, 2019, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/stalin-prize-winning-former-chief-writer-of-voice-of-america-news/.[/ref]Fast bragged in his 1990 autobiography Being Red that he “established contact at the Soviet embassy with people who spoke English and were willing to feed me important bits and pieces from their side of the wire.[ref]Howard Fast, Being Red (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1990), 18-19.[/ref] He also admitted that “As for myself, during all my tenure there [VOA] I refused to go into anti-Soviet or anti-Communist propaganda.”[ref]Howard Fast, Being Red (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1990), 23.[/ref] It meant in practice that wartime VOA would not broadcast any news critical of Stalin or the Soviet Union and would cover up his crimes to the greatest extent possible. Howard Fast formally joined the Communist party sometime in 1943, remained with the Voice of America until January 1944, and later worked as a reporter and editor for the party newspaper the Daily Worker.

I established contact at the Soviet embassy with people who spoke English and were willing to feed me important bits and pieces from their side of the wire. I had long ago, somewhat facetiously, suggested “Yankee Doodle” as our musical signal, and now that silly little jingle was a power cue, a note of hope everywhere on earth…

Howard Fast, Being Red (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1990), 18-19.

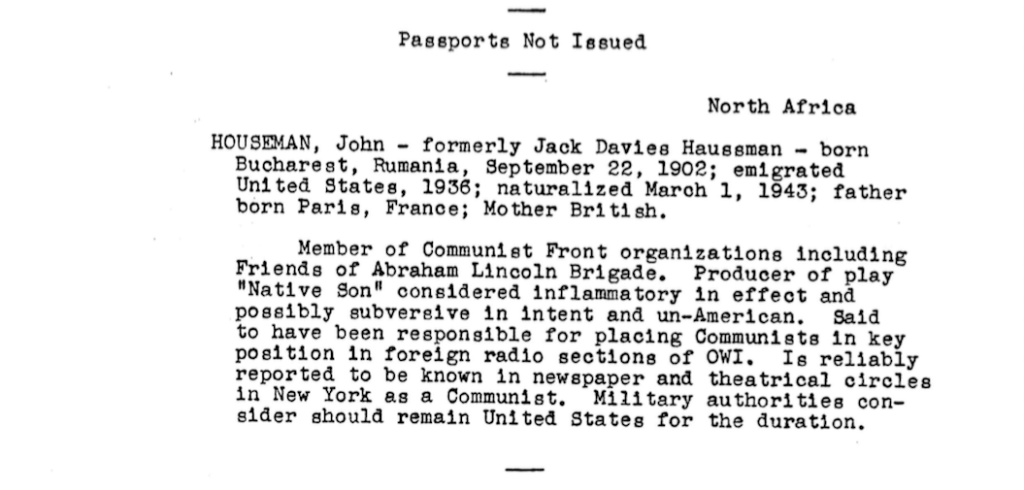

In the official version of VOA’s history, John Houseman resigned from his U.S. government job voluntarily, but he left the Office of War Information under strong pressure from the State Department. In April 1943, Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles, a key member of the Roosevelt administration foreign policy team and a close friend of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, in an attachment to a then-secret memo to the FDR White House, accused Houseman of hiring communists to work on U.S. government radio broadcasts for overseas audiences.[ref]Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles April 6, 1943 memorandum to Marvin H. McIntyre, Secretary to the President with enclosures, Franklin D. Roosevelt Library and Museum Website, Box 77, State – Welles, Sumner, 1943-1944, http://www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/_resources/images/psf/psfb000259.pdf. The Welles memorandum is also accessible at: State – Welles, Sumner, 1943-1944, From Collection: FDR-FDRPSF Departmental Correspondence, Series: Departmental Correspondence, 1933 – 1945 Collection: President’s Secretary’s File (Franklin D. Roosevelt Administration), 1933 – 1945, National Archives Identifier: 16619284, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/16619284. Also see: Ted Lipien, “First VOA Director was a pro-Soviet Communist sympathizer, State Dept. warned FDR White House,” Cold War Radio Museum, May 4, 2018, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/state-department-warned-fdr-white-house-first-voice-of-america-director-was-hiring-communists/. [/ref]

None of the accusations against Houseman were made public. The only false conclusion in the State Department’s notification to the White House was that Native Son was a subversive and un-American novel. Its African-American author, Richard Wright, was at one time a Communist Party member, but he eventually broke his links with the party and exposed its intolerance in later books. Because of his refusal to submit to party discipline, other communists called Richard Wright a “traitor.” In 1936, they beat him up when he tried to join marchers in the 1936 Communist Party May Day demonstration in Chicago:

…my hands were smarting and bleeding. I had suffered a public, physical assault by two white Communists with black Communists looking on.[ref]Richard Wright’s essay in Richard Crossman, ed., The God That Failed (New York: Bantam Books, 1959), pp. 143-145.[/ref]

The State Department note also described Houseman as a “Communist,” but there is no record that he had formally joined the Communist Party.

What doomed Houseman’s federal career was the State Department’s decision to deny his request for a U.S. passport for his planned official U.S. government travel abroad. The addendum to the Welles memorandum stated that military authorities, most likely the U.S. Army Intelligence (G-2), concurred with the State Department’s conclusion that Houseman should not travel outside the United States for the duration of the war.

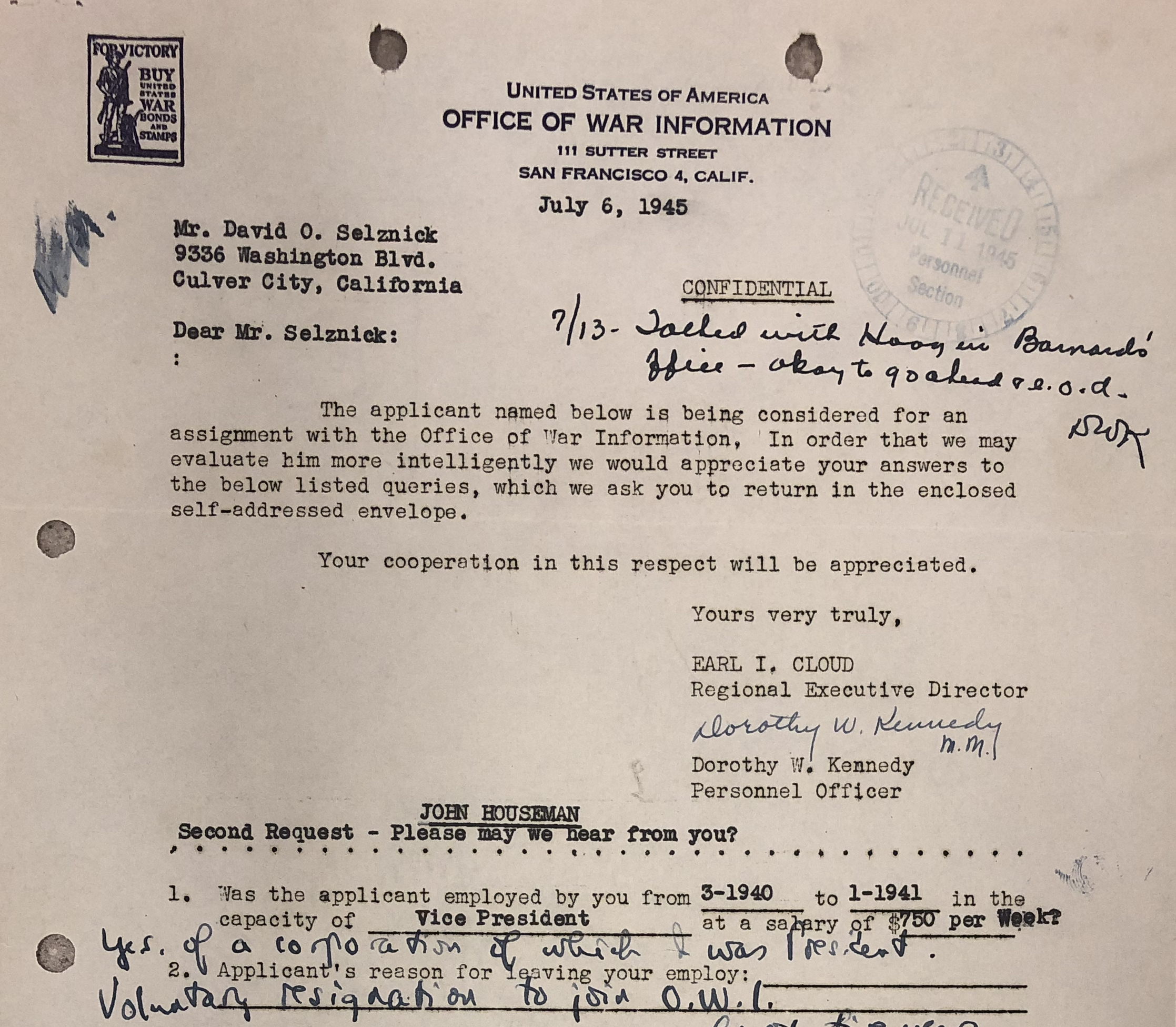

After Houseman resigned his director’s position in mid-1943, he continued to work for the agency for a few more months as a consultant. When shortly after the war, the OWI wanted to rehire Houseman in 1945 for another high-level position based in Germany, the State Department once again refused to give him a U.S. passport. Houseman’s former boss in Hollywood, studio executive David O. Selznick, wrote in 1945 on a confidential U.S. government background investigation form that “Only worry would be allegedly extreme leftist views, which possibly misunderstood and exaggerated [sic] in gossip.”[ref]John Houseman OWI Personnel Records.[/ref]

“Only worry would be allegedly extreme leftist views, which possibly misunderstood and exaggerated in gossip.”

David O. Selznick about John Houseman, 1945.

“But our main instrument of propaganda remained The Voice of America…”

John Houseman, Unfinished Business (New York: Applause, 1989), 249.