Voice of America Doctor Who Brought AIDS Information to USSR and Saved Lives

By Ted Lipien for Cold War Radio Museum

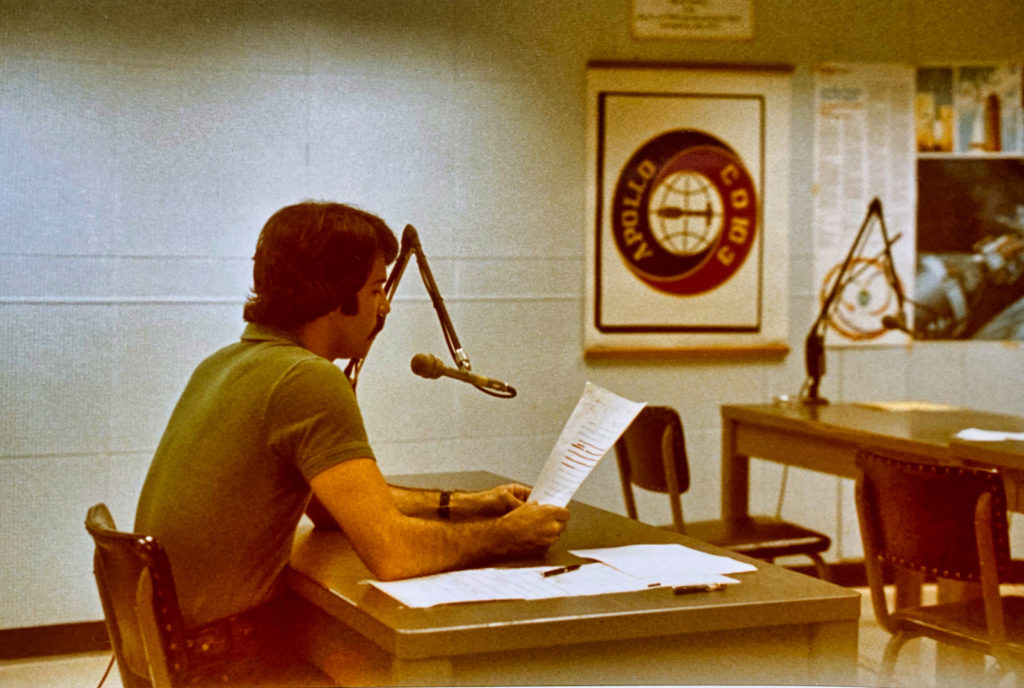

At one time during the Cold War, the taxpayer-funded, U.S. government-run broadcaster, the Voice of America (VOA), helped to save the Soviet Union from the danger of ignoring the AIDS epidemic. VOA brought AIDS for the first time to the attention of ordinary Russians during Ronald Reagan’s presidency before glasnost and perestroika were introduced in the USSR. Mikhail Gorbachev was only beginning his term as the General Secretary of the Communist Party and Russia’s current leader Vladimir Putin worked as a KGB officer in East Germany.

Dr. Irene Kelner, a Soviet-born physician turned journalist who was working for the Voice of America in Washington, DC, realized in the mid-1980s that the Kremlin’s information blackout about AIDS was having a deadly effect on the population in the Soviet Union. In an effort to save lives, she started to publicize in her Russian-language broadcasts accurate scientific data about the disease’s rapid spread and offered advice on prevention of infections from HIV, the virus which causes AIDS. The Voice of America got the attention not only of ordinary Soviet citizens listening on shortwave but also through its radio programs alerted Soviet doctors and eventually some Soviet government officials to the need of changing their own information policy on AIDS. This remarkable but little known accomplishment was largely due to early and persistent efforts of Dr. Irene Kelner who at the time was the author and host of the “Medicine and Health” program broadcast weekly to the Soviet Union by VOA’s Russian Service.

The first obstacle Dr. Kelner had to overcome were not Soviet censors but her own management. She had to convince managers in charge of VOA’s Russian Service that programs on AIDS were desperately needed and could save people’s lives. She told me in March 2020 that in 1985 the senior management of VOA’s Russian Service had to be persuaded that more attention should be paid in broadcasts to the growing AIDS epidemic. Most patients who suffered from AIDS in the United States at that time were homosexual men. Homosexuality was outlawed in the USSR, carried a strong social stigma, and some VOA managers might have been afraid that the Russian Service’s reputation could suffer among its audience if its programs focused on gay men. After assuring a senior supervisor that she would use only scientific terms about homosexuality, Dr. Kelner was given permission in the summer of 1985 to produce her first report on AIDS. She stressed, however, that Russian Service chiefs, Natasha Clarkson and later Marina Oeltjen, were each highly capable managers and strong supporters of her work as the author and host of medical and other programs. I asked Marina Oeltjen, who is now retired, about Dr. Kelner and she told me that she did an outstanding job, especially through her reporting about AIDS. Dr. Kelner also found a supporter in former VOA Russian Service chief Victor Franzusoff who by the time she came to VOA was a senior writer and commentator in the USSR Division. Irene Kelner told me that she was listening to Victor Franzusoff’s programs when she was still in the Soviet Union.

I contacted Enver Safir, former VOA Russian Service broadcaster and later regional marketing director for VOA and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL) programs in Eurasia and the Middle East, also now retired, who remembered voicing radio scripts for Dr. Kelner’s medical program. Jack Murphy one of several American-born linguists and journalists who learned Russian at American universities and were employed by VOA to work in the Russian Branch, did not participate in Dr. Kelner’s programs but knew about her medical show. He left his VOA job in 1985 and later returned to a number of managerial positions before his retirement. He mentioned that the VOA Russian Branch was quite cliquish in those days, but from what I could learn, Dr. Kelner was well-liked by the management, and got along well with both older and newer Russian immigrants, and with U.S.-born VOA broadcasters. She did not get involved in office politics as she was always busy working on her programs. Rewarded with a number of promotions, she retired from the Voice of America in 2008 from her last job as the managing editor and the head of VOA Russian radio broadcasting after a very successful career. She and her husband live now in Northern Virginia.

When I asked her about the current coverage of the coronavirus pandemic by the Kremlin-controlled media in Russia, she responded without any hesitation that it is “untruthful.” In answering my questions, she told me that the VOA Russian Service has not tried to contact her after her retirement. She said she hopes that they already focus on the heroic work of doctors treating coronavirus-infected patients (her daughter-in-law is a physician). She also mentioned the important work of nurses, virologists who developed the diagnostic tests, volunteers, and efforts of officials at federal state and local levels who try to contain the spread of the COVID-19 virus. From the beginning of the current medical crisis, she has been active on Facebook posting information about the coronavirus hotspots in Italy, Seattle and New York.

The challenges faced by media consumers today are different than during the Cold War, but propaganda and disinformation still make it difficult to distinguish between true and false information and true and false statistics, especially in news reporting and in social media posts about medical and other scientific issues. Dr. Kelner knows this better than most people as one of many former Voice of America broadcasters who earlier helped to break the monopoly on information held by officials in the Soviet Union and in other countries ruled by communist regimes. During the Cold War, media censorship and propaganda prevented millions of ordinary Soviet citizens, medical professionals and government officials from accessing true and accurate information not only on AIDS but also on almost all topics that had any chance of reflecting poorly on the Communist Party. By providing the latest medical news from the United States over many years, Dr. Kelner made a significant contribution toward AIDS education in the USSR. Her worked continued even after the information ban was weakened during glasnost and perestroika and in the period following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

As Irene Kelner stressed to me in our telephone interview, during her early years with VOA, AIDS in the USSR was still a taboo topic. Soviet media mentioned HIV/AIDS for the first time in 1987 when the first case was diagnosed in the country.

As AIDS was discovered and infections multiplied around the world, Soviet propagandists placed limits on media reporting about AIDS in the USSR itself while also spreading false claims that the HIV virus which causes AIDS was developed by the U.S. military. Soviet doctors were under pressure from the authorities to report cases of HIV and AIDS as other illnesses, and officials failed to warn the public about the exact nature of the disease and methods of its prevention. Dr. Kelner became concerned that the lack of scientific information in Russia and disinformation would have a devastating effect on the health of people living in the Soviet Union unless official and societal attitudes toward the illness were quickly changed.

In her first VOA Russian Service report about the AIDS epidemic, Dr. Kelner called it “Syndrome of Loss of Immune Functions,” in Russian “Синдром утраты иммунологических функций.” At that point, no one yet knew how the disease would be officially called by the Soviet medical authorities. Later, the Russian term for AIDS became СПИД, which was the exact translation of the English abbreviation for “Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome.” Since that time, every future VOA Russian Service program of “Medicine and Health” which she authored had short, 2-3-minute reports about AIDS. It eventually became a regular program segment called “All about AIDS” which was also included in her “Medicine and Health” radio show. Dr. Kelner told me in March 2020 that in her VOA Russian programs she covered many aspects of AIDS, both medical and social.

I described the disease itself and how it came to the U.S. from Africa through Haiti, who the first patient was, and what categories of people were most vulnerable (not only gays but also individuals who had blood transfusions, immigrants from Haiti, etc). I reported on the discovery of the HIV virus in 1985, AIDS diagnostic tests, ways of transmissions, changing of blood donations procedures, treatments, the work of AIDS activist groups, and many other aspects of the disease.

One of the scientists Dr. Kelner interviewed for her VOA radio programs on AIDS was Dr. Anthony Fauci, the current director of of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases who is now a leading member of the White House Coronavirus Task Force working on stopping the coronavirus pandemic in the United States. At the time when she worked for the Voice of America, he was one of the dozens of AIDS experts, and not yet the most famous one, who participated in her programs. She also interviewed Dr. Robert Gallo and Luc Montagnier who discovered the HIV virus, WHO expert Dr. Jonathan Mann, and Dr. Matilder Krim who helped to increase public awareness of AIDS and to combat prejudice against AIDS patients. Dr. Kelner recorded and broadcast many other interviews while covering at least ten international AIDS conferences between 1989 and 2002.

Her programs provided not only the latest scientific and medical news. They also contributed to easing some of the strong social intolerance toward AIDS patients, drug abusers and other groups who were marginalized in the Soviet Union. Homosexual acts between men were finally legalized in Russia in a law signed by President Yeltsin in 1993. However, discrimination against LGBT individuals intensified again later under President Putin with the passage of a federal law in 2013 banning the distribution of “propaganda of non-traditional sexual relationships” to minors.

In addition to her programs on AIDS, Dr. Kelner also discussed many other non-AIDS-related medical topics and promoted cooperative medical and other scientific exchanges between the United States and the Soviet Union, and later with the Russian Federation and other post-Soviet independent states.

In 1989 she had another major achievement. Dr. Kelner was mentioned in a New York Times article as the Voice of America medical program host who helped to arrange a lifesaving operation in the United States for a one-year-old Russian boy suffering from a brain tumor. Thanks to her efforts of reaching out to an American charitable foundation and putting American and Soviet doctors in touch with each other, the successful surgery was performed at the Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx. She told me that her involvement originated with a letter she received from the boy’s grandmother in Moscow.

One letter I received at the end of 1988 contained a piercingly written plea for help. A grandmother wrote about a fatal illness of her one and a half year old grandson. He had a brain tumor. In the USSR, such small children were not operated on since the doctors did not know the methods of giving general anesthesia at such a young age. In the meantime, this benign tumor had grown and squeezed on other very important parts of the brain. Shortly before receiving this letter, I interviewed Marcy Rogers, founder and president of the International Craniofacial Foundations in Dallas which arranged for free maxillofacial operations for children from other countries (they mainly brought young children and teenagers from South America). I thought that her foundation could help a seriously ill boy from Moscow, and they did.

Irene Kelner was born at the end of World War II in Moscow in a Jewish family. Bright and hard-working, she received her medical degree in 1967 from the prestigious First Moscow Medical School and later got a Ph.D. in the field of cancer immunology. Even before finishing her studies, she had written several scientific papers in the field of experimental oncology and won a prize at a major scientific competition. While life was not easy in the Soviet Union, especially for a young Jewish woman, her scientific research and accomplishments helped her get a job at the Laboratory of Leukemia Immunology of the Central Research Institute of Hematology and Blood Transfusion in Moscow. In the USSR, it was much more desirable for a physician to do research, but as a regular listener to the Voice of America broadcasts, she already knew that she did not want to spend the rest of her life and her career under repressive Soviet communism. When the Soviet authorities loosened restrictions on emigration, she left in 1974 to go the United States with her first husband who was a well-known journalist and writer. They settled in Cleveland, Ohio because the Jewish community in that city was their sponsor, and she started working at the Molecular Biology Lab of the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine.

She and her first husband moved to Washington in 1976 when he got a job with the VOA Russian Service. She found work at the National Cancer Institute, part of the National Institutes of Health, in Bethesda Maryland, where she continued her cancer research. She also started to give interviews to VOA from time to time about her scientific work.

In 1981, a VOA woman broadcaster who interviewed her suggested that she apply for a full-time position which opened up in the Russian Service. At first she did not take the suggestion seriously, but later realized that it might be a good change for her while she was raising her young son. Most of the other researchers she worked with at the NIH were unmarried young men in their early 20s from various countries around the world. She was required to be at the lab at least 14 hours a day since her experiments were done around the clock. In July 1981, she took translating, writing and voicing tests at the United States Information Agency (USIA) building on Pennsylvania Avenue NW near the White House. USIA, which no longer exists, was then VOA’s parent federal agency. She told me that it was a very hot day with the temperature outside hovering over 100 degrees. Her only wish was to finish the long exam, especially the part when she had to read her English-to-Russian translation at a sound-proof booth with no AC.

Dr. Kelner told me that she quickly forgot about the test and continued to look for jobs in her professional field, and even had some promising conversations with a couple of scientists but no real job offers. Then suddenly in December 1981, she got a phone call from the VOA HR department with the news that she had passed the tests and could start working after getting a security clearance. She was hired on February 16, 1982, making a transition from a scientist to a radio broadcaster and a journalist.

Dr. Kelner thought initially that her radio job would be a temporary one while she was raising her son who was born in Cleveland, Ohio a month-and-a-half after she came in the U.S. Mark Kelner, now 45, is an artist, married, and lives in Washington DC. He was interviewed in 2019 for an article in the Washington Post about his “Solaris: Shelter for the Next Cold War” art exhibit.

When Dr. Kelner moved from the NIH to VOA in 1982, which meant taking a pay cut in her government salary, she assumed that after her son got a little older she would go back to scientific research. But after starting her regular medical radio programs and realizing their impact in the USSR, radio broadcasting became her permanent career. “I thought that I would work at VOA for a couple of years…, but the work itself was so interesting that it became a second career for me, a career which I loved and in which I advanced,” Dr. Kelner told me. She described to me her job in the Russian Service as enormously fulfilling, and she also credited the Voice of America with changing her life even earlier when she was still very young and living in the Soviet Union.

I first heard the Russian broadcasts of Voice of America in 1956 during the revolution in Hungary. I was 12 years old. Since then I continued to listen to VOA Russian programs for the rest of my stay in the Soviet Union. These programs have shaped my worldview and political ideology, forever making me anti-Soviet. I could never imagine that I might leave the USSR and one day become a VOA Russian Service broadcaster. The years I spent at the Voice of America were perhaps the most interesting period of my professional career, and I often recall this time.

Before I started my VOA job, I was sure that I would write for the Russian Service’s medical program which already existed at the time. It was prepared by a couple of staffers with no background in medicine. But on the first day, I was told that I had to learn how to do news and political reports. The only medical assignments for me were the obituaries which I had to translate into Russian and describe the correct cause of death. After my scientific research job at the NIH, writing news, radio scripts and being on the air felt like a vacation.

My first medical program started a year and a half later after one of the contributors to the medical program suddenly died. Natalie Clarkson who was the head of the Russian Service came to me and said that from now on I will have two days for the preparation of the seven-minute radio segment called “Medicine and Health.” I said that I will do it but only if I would MC the program myself and would be allowed to choose all of its topics.

And I started… First, I realized that in two days I could do much more than than a seven-minute broadcast. I started to accumulate a lot of material. I used central VOA English-language scripts and newspaper articles. I interviewed doctors and other medical professionals. I read magazine articles about medical discoveries and wrote my own reports based on what I had read. I also tried to develop my own content for my program and felt like I had found a goldmine of useful knowledge.

After about a month, I went to my boss and showed her all of my research materials, saying that I needed more air time. At first, she misunderstood what I was saying because she thought that I came to ask for more time to prepare my program, but I explained that my request was quite the opposite; I wanted more airtime. She then took me to the office of the VOA USSR Division director and told me to explain my ideas to him (I don’t remember his name). He asked me just one question: “Since you almost never use central VOA English scripts to translate, how do you choose the topics for your program?” I said: “I only use topics that interest me personally, and because of that I can prepare a program which will be of interest to our audience.” He said: “I have never heard something like that!,” and I got 15 minutes for my “Medicine and Health” show.

Meanwhile my private life changed.

In April 1984, after my divorce became final, I married a very good man, Leonid Kelner, a physicist who had left Russia for Israel in 1972, worked there at the Weizmann Institute of Science, and in 1975 while attending a scientific conference in the United States received a job offer from the National Institutes of Health Biomedical branch. He is now retired after working for NASA and in private business. We have been happily married for almost 36 years.

After my remarriage, I was allowed to change my name on the air from Dr. Irina (for Irene in Russian) Suslov to Dr. Irina Kelner. Such a change of radio name was unprecedented at Voice of America, or at least that’s what I was told…

My first out-of-town reporting assignment was in March 1985. I was asked to cover the Special Olympics Games at Park City, Utah. Prior to that I had never heard about Special Olympics. But covering the Special Olympics and interviewing participants and organizers, including Eunice Shriver (JFK’s sister) and Ted Kennedy, I learned how to be a reporter. I was able not only to send daily feeds to VOA but brought back with me a lot of material to make additional programs about the history of the Special Olympics movement, which was largely unknown in the USSR. Since I couldn’t afford Park City’s hotels on the government per diem, I stayed at Salt Lake City. During a break in my reporting work, I went to the University of Utah Medical School because several months earlier the first artificial heart transplant was done at the University of Utah Hospital. I was very lucky to meet Dr. Willem Kolff, a physician and inventor who developed the first functioning artificial kidney.

Dr. Kolff was a pioneer in the field of of hemodialysis and artificial organs. I didn’t make an appointment with him but just came to his lab. I introduced myself as a scientist, medical doctor and a Voice of America journalist. We had a long talk (about an hour-and-a-half since Dr. Kolff was also interested in the Soviet Union). I recorded it (minus our talk about the USSR) for future programs. After that Dr. Kolff took me on a tour of the facility which had calves with artificial hearts, and I recorded the sounds of artificial heart beats. (Later these sounds opened my program segment about medical innovations.) Leaving the University of Utah, I was so truly exited having with me priceless materials which I later used in many of my programs.

After reviewing my reporting from the Special Olympics, the head of the Russian Service sent me on another reporting assignment 10 days later. I went to Atlanta to cover the First Ladies Conference on Drug Abuse. Nancy Reagan was there promoting her “Just say NO” campaign. I prepared many feeds for VOA programs, including an interview with Nancy Reagan. It was very useful material for my audience since officially there was no drug problem in the Soviet Union. This was, of course, not true. The drug problem in the USSR was covered up and pushed underground. After my reporting from the Atlanta First Ladies Summit, my medical show was increased to 43 minutes. It was the maximum airtime I could get because at the beginning of the hour there was a 15-minute newscast and at the bottom of the hour, a two-minute news summary. I had four days a week to prepare and record the program.

In a couple a of months after that, I was promoted to a position of an editor in the Russian Service.

After the collapse of the USSR, I continued to be the author and host of the “Medicine and Health” show. In 1993, I also developed a ten-minute program on parenting difficult children. While visiting Moscow, I realized how challenging it was for mothers and fathers to raise their children after the collapse of their country and dissolution of the familiar world. I made arrangements with two psychologists: Dr. Florence Kaslow, president of the International Family Therapy Association (the VOA Special Events department helped me find her), and Marsha BenDavid, a special education teacher at the New York School for Children with Psychological Problems, whom I knew before.

These experienced specialists agreed to participate in pro bono phone interviews with me twice a month. In selecting topics for the interviews, I used some of my own experiences as a parent raising my own child after a divorce and starting a new marriage. I thought it would be useful to share some of my own private life with my audience in addition to interviewing specialists. I prepared more than 130 programs called “Parenting School” which were broadcast for more than two and a half years and offered advice on raising children at the time when a new way of life was beginning in the CIS countries.

During that time, I continued to travel to Moscow on professional and personal business. Once I had to spend a day at a newly-established private Russian company. I watched how the work of this company was organized, and I did not like what I saw. After returning to Washington, I convinced my husband’s business partner, who had been a successful businessman for many years, to do a pro bonoweekly telephone interview on various aspects of managing private enterprises. I started to prepare a seven-minute weekly program called “Principals of Management” and produced and hosted over 120 segments.

VOA radio broadcasts in Russian were no longer jammed and our audience wanted to know more about what was happening in the former Soviet Union. I always took this into account when preparing my broadcasts. For example, in 1997, I was sent to the Russian city of Novgorod to cover a conference of international specialists on infectious diseases. The topic of that conference was the diphtheria epidemic that broke out in the Russia in 1995, from which thousands of people died.

Then I went to Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan to collect material for the programs on the causes of a significant increase in children mortality in the newly formed states of Central Asia. Numerous interviews with doctors, nurses, hospital managers and ministers of health, as well as visits to children’s hospitals and maternity wards in these newly independent countries gave me the opportunity to conduct a comprehensive analysis of the causes of this terrible phenomenon. I prepared a series of programs about the events taking place in the field of healthcare in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.

Then, due to the reduction in 1999 in the duration of shortwave radio broadcasts, the “Medicine and Health” program was reduced to daily 8-10 minute reports on new medical discoveries, and I started to work as an editor of radio and television programs, and also as a radio and TV reporter.

In the period following the 9/11 attacks, I prepared programs for two months about doctors who saved and treated the 9/11 victims in New York and in Washington, and about the efforts to restore normal life. I also started doing live talk shows on medical topics, inviting Russian speaking specialists from various fields of medicine to VOA studios where they answered questions from listeners. I also conducted radio bridges with Russian-speaking American doctors and Russian doctors who shared with each other information about their work and answered questions from VOA radio listeners.

At the end of 2002, I was promoted to be a team leader and senior editor. I became the managing editor of the daily one hour show called “American Panorama” about life in the United States. I edited and hosted the show. In 2004, my responsibilities were expanded and I became the managing editor and host of the political show called “Events and Opinions,” which had been the main political program of the VOA Russian Service. By that time, Marina Oltjen, with whom I worked in a friendly tandem, became the head of the Russian Service. She helped me a lot, guiding me in my coverage of political events in the CIS countries.

It was not an easy job for me, since previously I had never directly dealt with political reporting. However, short-wave radio broadcasting was reduced to three hours and most the experienced staff had retired. No new journalists were hired to replace them. The morale of the remaining employees was poor. The lion’s share of my time was now devoted to television, preparing a daily 30-minute TV program. After Marina Oeltjen retired, my job became even more complicated by the lack of experienced writers and broadcasters. I often had to completely rewrite programs submitted by poorly-trained new contractors.

My responsibilities also included scheduling weekend programs, because on weekends only a few people wanted to work in the Russian Service. Those few who were assigned to work only prepared newscasts and read them on the air. Other programs were prerecorded and all of them were already broadcast during the previous week. The Russian-language radio from Washington was gradually dying.

I retired from VOA at the end of June 2008 after 26-and-a-half years of working in the Russian Service. I started as a news writer and finished my career as a senior managing editor and radio programs head. I was 64 and became very tired. As I later discovered, I was suffering from an illness. By that time, some of the most capable people had already retired and I was extremely frustrated. It was the right time for me to retire. A week after I left, Russian-language shortwave radio broadcasts were discontinued. Everything was on the Internet. Needless to say that in 2008 many of our former radio listeners in the Soviet Union did not have access to the Internet.