VOA Guide For Writers and Editors Circa 1972

By Ted Lipien

Shortly after I had joined the Voice America (VOA) Polish Service 46 years ago in December 1973, the management provided me with a copy of the VOA Guide For Writers And Editors. There were not enough of these Guides, so I had to share it with one other broadcaster in the Polish Service. The Guide was prepared primarily for use by writers and editors in the VOA Central English Newsroom. Most of the time we were translators, not news writers. VOA language services were not allowed to originate their own news reports except in very rare circumstances and always under close supervision of managers in the European Division, the VOA Newsroom or the VOA Current Affairs Division. But the Guide provided us with useful information on the requirements of the VOA Charter in making VOA news “accurate, objective and comprehensive.” It also helped foreign language broadcasters to learn how the VOA Newsroom operated. I remember being particularly impressed by VOA’s two-source rule to assure accuracy of VOA news:

If you have a first-hand source that is all you need. If you do not you must have two sources, such as reports from two wire services. Even two sources require careful evaluation.

In 1973, I already knew that the Voice of America was a government radio and was part of the United States Information Agency (USIA), a public diplomacy arm of the U.S. State Department, but the Guide explained to new employees how policy guidance was to be observed by VOA writers and editors. This was again of interest mainly to the VOA Newsroom and the VOA Current Affairs Division staff. In the foreign language services in the European Division, most of our work consisted of translating centrally-prepared English news, news analyses and press roundups. A foreign language broadcaster might have been allowed to produce one original program per week but not a news program that would require discussing U.S. foreign policy. VOA service chiefs might have had access to policy memoranda, but these policy guidance documents had no impact on our daily work and I don’t remember seeing any in the 1970s. From time to time, the service chief would tell us what was the official U.S. administration position on a particular foreign policy issue.

Twice daily we receive brief memoranda from the VOA policy office. This is the only channel for policy guidance to VOA. Under no circumstances should you take any action concerning policy matters on the basis of suggestions or advice from other sources. Since VOA is government radio and U.S. government actions and policies are major news, policy guidance is useful and necessary. You are reminded, however, that the policy mechanism is not authorized to suppress or alter news items by invoking policy considerations. If you spot problems in this area, call them to the attention of your editor at once.

The policy office was not at that time as important or as sinister as someone outside of the U.S. government might suspect. I eventually discovered that while policy guidance memoranda caused a few major incidents of censorship at the Voice of America, on a daily basis in the 1970s most of the censorship and limitations on legitimate news coverage, especially by VOA foreign language services, were self-imposed by upper-level, mid-level and lower-level managers, as well as by some of the VOA journalists themselves. Broadcasters in the foreign language services knew from their service chiefs what kind of reporting would be tolerated and what was being discouraged. In broader terms, the allocation of resources by the management greatly favoring the central English-language services made it impossible for foreign language journalists to initiate original news coverage on their own. The system was designed to maintain central control by the VOA Newsroom and the Current Affairs Division and to employ a large number of English-language writers, editors, reporters and foreign correspondents.

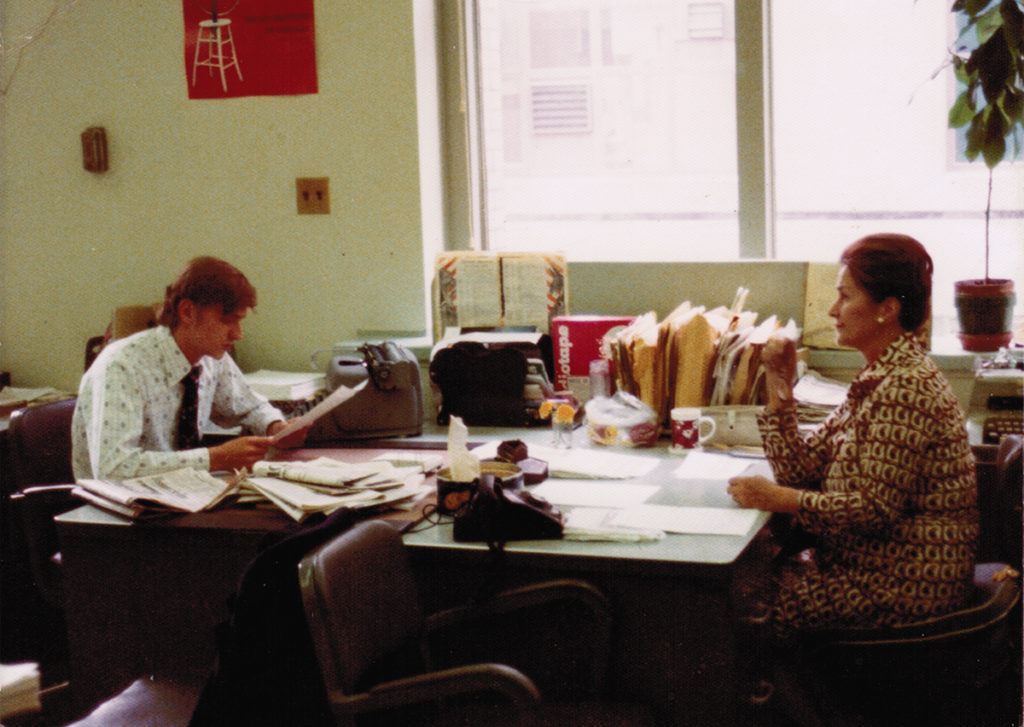

The Guide which I received was prepared primarily by Herb Little, former Deputy Chief of the VOA News Division who at the time of its publication in the early 1970s had already retired. The booklet was updated by Duncan Scott, the then Deputy Chief of the VOA Newsroom. It was approved for publication by Charles L. Eberhardt, the then Chief of the VOA News Division. I don’t recall knowing any of them. During my early years at VOA, I had very little contact with the central management or the Newsroom. The situation at the Voice of America changed dramatically when officials appointed by the Reagan administration ushered in management reforms in the 1980s and gave more resources to VOA’s foreign language services to originate their own news coverage of events related to their target countries. When the independent Solidarity trade union began its struggle for democracy and I became the chief of the Polish Service, I was finally able to file reports in English for VOA News and put to use some of the tips in the VOA news writers’ Guide.

The VOA Guide For Writers And Editors, which I still have, was probably given to me in the early 1970s by the then chief of the VOA Polish Service Marian Woźnicki, his deputy Zdzislaw Dziekoński or perhaps the service’s secretary, archivist and part-time radio producer Ewa Jaxa-Dębicka. I don’t remember who among them actually handed me the Guide and told me to study it in my spare time. I also don’t remember how soon I got it after joining the Polish Service. It could have been in 1974.

I also was not able to determine precisely when the edition of the Guide which I received was written and printed. Judging from some of its content, it could have been written in 1972 or perhaps somewhat later.

Although the booklet was not designed specifically for the VOA language services, I found the Guide to be a useful reference for my own training in radio journalism. For many years neither I nor any of my colleagues in the Polish Service were able to put much of the knowledge in the Guide to any practical use while working on preparing VOA Polish broadcasts. I soon discovered that journalists in VOA’s foreign language services were mostly required to translate centrally-prepared news items and news reports written in English. In the 1970s, they were rarely given any opportunities to write original radio scripts or do any original reporting on their own in their own languages or in English.

Although some of the Guide’s language may appear now slightly patronizing toward foreign-born journalists, I don’t remember that it bothered me at the time. What bothered me was the fact that we were prevented by VOA’s middle and upper management from analyzing such historical topics as the Soviet executions in 1940 of more than 20,000 Polish military officers and intellectual leaders, collectively known as the Katyn massacre. During World War II, the Voice of America spread Soviet propaganda lies about Katyń and for several years after the war avoided reporting news about Katyń and other Soviet atrocities, limiting any such reporting to at best short news items. Then under considerable bipartisan pressure from the U.S. Congress, VOA started to report extensively on Katyń and other similar topics, but the silent treatment returned after a few years and continued during the 1970s.

Only much later I learned that the original staff of the Voice of America Polish Service during World War II included mostly socialists and communists who broadcast Soviet propaganda and supported the establishment of a pro-Soviet regime in Poland. Two of them, Stefan Arski, aka Artur Salman, and Mira Złotowska, later known as Mira Michałowska, worked after the war as propagandists and journalists for the communist media in Poland.[ref]Ted Lipien, “Mira Złotowska – Michałowska — Soviet influence at WWII Voice of America,” Cold War Radio Museum, December 2, 2019, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/communist-mata-hari-at-wwii-voice-of-america/.[/ref] I also learned much later that the Voice of America’s first chief news writer in 1943 was Howard Fast, American communist and future winner of the Stalin Peace Prize.[ref]Cold War Radio Museum, “Created 70 years ago, Stalin Peace Prize went in 1953 to former Voice of America chief news writer Howard Fast,” December 21, 2019, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/created-70-years-ago-today-stalin-peace-prize-went-in-1953-to-former-voice-of-america-chief-news-writer-howard-fast/[/ref]

Initially, I accepted the myth perpetuated by the Voice of America management that from its very beginning in 1942, the Voice of America broadcast only truthful news. Only a few years later, I realized that some of the key old-time program managers knew about the Soviet influence at the Voice of America during World War II but for ideological, partisan and public relations reasons covered up the truth. Some of them later strongly resisted management reforms during President Ronald Reagan’s administration.

Several years before joining VOA while still living in Poland, I had made my decision to become a journalist when I had discovered that the communist media and most of my school teachers were lying about recent history of Soviet atrocities. My dream was to be a Radio Free Europe broadcaster, but because I came to the United States at the age of 16 to live with my father after the divorce of my parents, I ended up working at the Voice of America in Washington, D.C. I got the VOA job after responding to a Chicago Sun-Times newspaper ad for a broadcasting position in the VOA Polish Service. I passed the mandatory VOA translation, writing and voice tests apparently with flying colors because I was hired despite my young age and lack of any prior journalistic or broadcasting experience. However, I had listened regularly to Western radio broadcasts since a very early age, especially to Radio Free Europe and the BBC. While I was still living in Poland in the late 1960s, I found many of the VOA Polish programs to be rather official sounding, politically overly cautious and often boring, but there were a few VOA programs which were quite good.

My first impression in late December 1973 after a few walks through the Voice of America building at 330 Independence Ave., S.W. was of being in a slightly better-kept communist government complex somewhere in socialist Poland. Much of the VOA furniture and studio equipment dated back to World War II. The overall atmosphere was generally depressing. It was immediately obvious to someone coming from a socialist country that the government bureaucracy was firmly in charge of the broadcasting organization although nothing could compare to life under communist rule. I also realized rather quickly that while VOA was broadcasting some news being censored behind the Iron Curtain and its programs were in general against communism and Soviet-rule over Eastern Europe, reporting in depth in English or in any other language on certain sensitive topics dealing with communist atrocities in Soviet Russia and in other Soviet Block countries was discouraged by the VOA management in the new era of détente between Washington and Moscow initiated by Richard Nixon, Henry Kissinger and Leonid Brezhnev.

I soon resumed listening regularly to Radio Free Europe Polish programs to learn what was happening in Poland. RFE shortwave radio programs were heavily jammed by the communist regime, but shortwave reception in Washington of RFE broadcasts was more than adequate. The weekly reach of VOA Polish Service programs during the 1970s was only about 10 percent in Poland. RFE broadcasts were during the same time reaching weekly between 40 and 50 percent of adults in Poland even with much heavier jamming. RFE had, however, some advantage by being on the air with its Polish broadcasts for many more hours daily than VOA.[ref]R. Eugene Parta, Audience and Public Opinion Research Department (APOR) of Radio Free Europe and the East European Audience and Opinion Research (EEAOR) unit of Radio Free Europe/ Radio Liberty, “Listening Rates to Western Radio Stations in Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania and Bulgaria: 1962-1988” (Stanford: Conference on Cold War Broadcasting Impact, 2004).[/ref] The Voice of America had an impact by being associated much more closely than RFE with the U.S. government, but the amount of useful information provided by VOA about political developments in Poland and in the rest of the Soviet Block countries was rather minimal. VOA was also often late in reporting on East European news.

Despite all the discouraging circumstances beyond the control of the Polish Service, I was still enormously excited in the early 1970s about my new job as a VOA foreign language broadcaster trainee. I was also very eager to learn the VOA style of news reporting even if I couldn’t use it for my work at VOA. Only 20 years old and not yet a college graduate, I was really lucky that someone in Washington, most likely Mr. Woźnicki, had decided that the service could use a young person who had lived in communist-ruled Poland and knew the realities of life there better than some of the other Polish Service editors, writers and announcers who had come to the United States either before, during or immediately after World War II. I estimated the average age of the staff in the VOA Polish Service to be about 65 when I arrived there in 1973. By hiring me, VOA might have lowered the average age to perhaps 60.

Many of my older colleagues were, however, outstanding journalists, published authors and radio announcers in pre-World War II Poland. I realized quickly that they also felt stifled and disillusioned in the stagnating and bureaucratic environment of the 1970s’ Voice of America while the upper management, which killed their creativity, proclaimed in public that VOA was doing a terrific job broadcasting accurate news and commentary behind the Iron Curtain. In reality, it was much less of what the Polish Service journalists were capable of doing if they had been given a chance to use fully their knowledge and talent.

One of my much older colleagues in the VOA Polish Service at that time was Jerzy Tepa, a well-known Polish author of internationally-preformed plays: Ivar Kreuger, Jeanne de la Motte and Fraulein Doktor. Marek Swięcicki was a World War II Polish soldier, war correspondent, and author of With the Red Devils at Arnhem. His book about the famous World War II battle in which he participated as a war correspondent, originally written in Polish, was translated into several foreign languages. I also worked in the VOA Polish Service in the 1970s alongside Henryk Grynberg. Still writing and living in the United States, he is another outstanding Polish author of more than 20 books of prose and poetry (including two dramas) mostly on the Holocaust experience and post-Holocaust trauma.

When I joined the Polish Service, all of my colleagues were extremely welcoming and helpful. If I’m not mistaken, I spent the first Christmas in the home of Tomasz Dobrowolski who as I recall was a former prisoner in the Soviet Gulag. The famous former anti-Nazi Polish underground fighter Zofia Korbońska and her husband, Stefan Korboński, who was the last civilian head of the Polish underground state in German-occupied Poland, took me under their care. They had escaped from Poland in 1947 fearing imminent arrest by the Soviet and Polish secret police. Ewa Jaxa-Dębicka, who was married to a pre-war Polish diplomat but was separated from her husband, invited me to lunch at the Old Europe restaurant in Georgetown, where I had my first American shrimp cocktail. She also introduced me to Georgetown University professor Jan Karski, the World War II witness of the Holocaust who had provided a first-hand report to President Roosevelt on the German genocide of Polish Jews. They were a remarkable group of Polish refugees from Nazism and communism.