Maciej Wierzyński at Voice of America – ‘the Most Frustrating Period’ in the Life of a Refugee Journalist

Maciej Wierzyński at Voice of America

One of the most successful and popular Polish-American refugee journalists, Maciej Wierzyński, described his tenure at the Voice of America in the 1990s as the “most frustrating period of his life.”

By Ted Lipien

My successor as the Voice of America (VOA) Polish Service chief from 1994 until 2000 was a very talented former Polish Television and Radio Free Europe (RFE) journalist, Maciej Wierzyński. Toward the end of the Cold War, Wierzyński had worked for a popular Polish Television cultural and political program, “Studio 2.” Because of his liberal views and his support for the independent trade union Solidarity, communist authorities dismissed him from his Polish State TV job following the imposition of martial law in Poland on December 13, 1981.

Following his dismissal, Wierzyński worked as a taxi driver in Warsaw and as an assistant to a Washington Post correspondent. In 1984, he emigrated to the United States, where he also worked for a while as a taxi driver. Later, he published articles in Polish-American newspapers, worked in Chicago for the oldest Polish-American daily in the United States, Dziennik Związkowy, and started a Polish-American cable TV channel.

After the fall of communism in Poland, in 1990 Wierzyński became the first head of the Radio Free Europe bureau in Warsaw. He was hired by Piotr Mroczyk, the then director of the RFE Polish Service. Mroczyk had worked earlier in the VOA Polish Service in Washington when I was the service chief and Marek Walicki was my deputy.

Before the presidential elections in Poland in 1990, Wierzyński moderated the televised debate between Solidarity leader Lech Wałęsa and a maverick candidate, Stanisław Tymiński, a person with a somewhat mysterious background, connections and financial backing. Wałesa easily won the debate and the presidential election.

Wierzyński later worked for the RFE bureau in Washington. When the RFE Polish Service was abolished in 1994, he was hired by VOA as my replacement in Washington.

I left my position in the Voice of America Polish Service in 1993 to become the regional Eurasia marketing director in Munich and Prague for the Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG). I worked for what was then the parent federal agency for both VOA and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL).

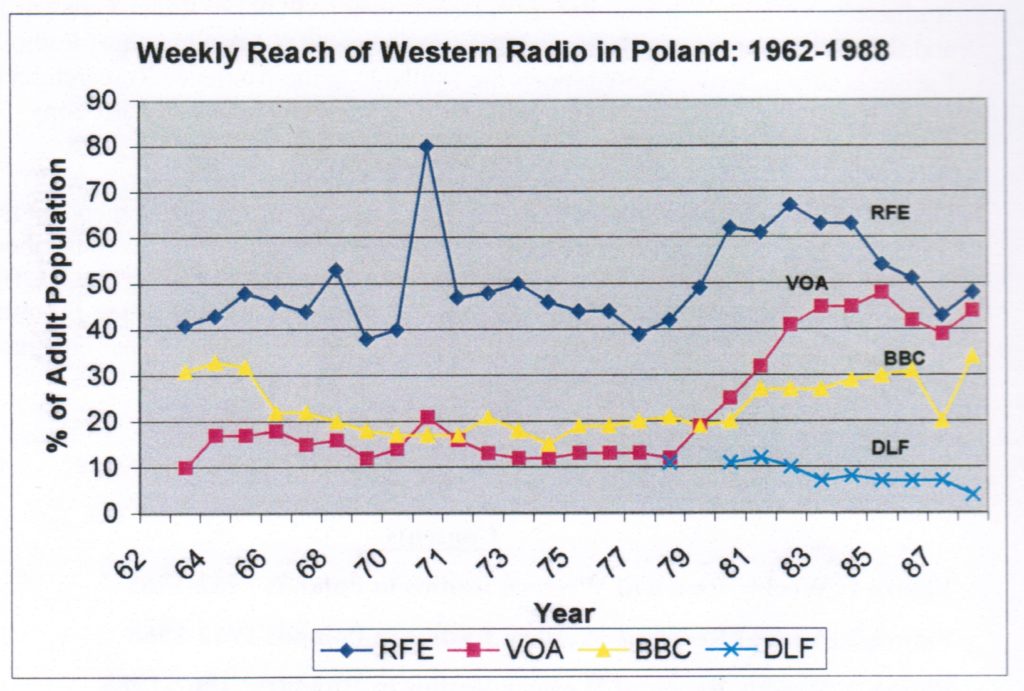

When Wierzyński took over, the fortunes of the Voice of America were already declining. The VOA Polish Service had its best period during the Reagan Administration, when our team of journalists managed to increase VOA’s audience in Poland from about 10 to nearly 50% of the adult population. Toward the end of the 1980s, our programs became almost as popular as the always superior RFE Polish broadcasts.

During those turbulent times, managers, who previously had made our work difficult, and some American-born journalists working in the VOA English newsroom, predicted that Reagan and his appointees would destroy VOA’s audiences and credibility. The opposite happened. Our programs surged in popularity–probably the steepest and the fastest program reach expansion in VOA’s history. In less than ten years, communism in East Central Europe collapsed, with Poland leading the way toward freedom and democracy.

When Maciej Wierzyński took charge of the Voice of America Polish Service in 1994, the old VOA bureaucracy–which had been sidelined for a while during the Reagan years, allowing the Polish Service to function more like a journalistic entity in the 1980s–was already back running VOA and occupying some of their former positions.

These WASP managers with a patronizing attitude toward Voice of America’s foreign language services, were not nearly as radical as the first VOA chief writer and news director Howard Fast, but they were almost as naive about communism and the Soviet Union as their predecessors during World War II and immediately after the war before VOA was reformed by the Truman Administration. Fast had worked for VOA during the war. In 1953, he had received the Stalin Peace Prize. As a communist admirer of the New York Times Pulitzer Prize winner Walter Duranty, who in the 1930s repeated Soviet propaganda lies and covered up Stalin’s crimes, Fast and other wartime broadcasters did the same at VOA.

Wierzyński’s, and earlier my bosses at the Voice of America, hid the existence of these early pro-Soviet VOA fellow travelers. They would not tolerate or promote anyone who disagreed with them on U.S. domestic and international politics. As an independently-minded foreign-born journalist without prior experience in dealing with the government bureaucracy in Washington, Wierzyński had no chance to carry out his ambitious programming plans. He would get no support and no money from the VOA bureaucracy, and became increasingly frustrated.

We had experienced a similar treatment and stagnation in VOA’s foreign language services in the 1970s during the administrations of Presidents Nixon, Ford, and Carter. As a broadcaster, reporter, and later editor, I did not have an easier time in the pre-Reagan years, but my strategy was not to share with the radically partisan American-born senior managers my real views, or to inform them of some of our coverage plans, which I knew they would kill. The Reagan Administration finally gave me and the journalists in other VOA East European foreign language services much needed resources and a few years of journalistic freedom. This period ended at the conclusion of the Cold War, shortly after the departure of the Reagan Administration.

When Maciej Wierzyński came to VOA in 1994, he was already out of luck. I tried to help him, but by then not much could be done. He and I visited radio stations in Poland to arrange successfully for local placement of VOA Polish programs. I liked him and enjoyed our conversations. He told me about interesting episodes in his life in the communist-ruled Poland and in the United States, but I could not help him much in dealing with VOA’s Washington bureaucracy. Nobody could.

The then VOA management had returned to protecting their own jobs and those of American-born English-language programs editors, writers, and reporters. As before, they did it at the expense of VOA’s foreign language services and the anti-communist refugee broadcasters. The good and exciting Reagan years were over before Wierzyński came to work for VOA. He was not able to put to much use his considerable television and journalistic talents.

Maciej Wierzyński described his tenure at the Voice of America in the post-Reagan years as the “most frustrating … in his life.” He wrote about it briefly in his essay, “Second Half of My Life,” for the book, Autroportret zbiorowy: wspomnienia dziennikarzy polskich na emigracji z lat 1945-2002 (Collective Self-Portrait: Memoirs of Polish Journalists in Exile from 1945 to 2002). The book, edited by Wiesława Piątkowska-Stepaniak, was published by the Opole University in Poland in 2003. He titled the section of his reminiscences about VOA “Exiled to Washington.”

The book also includes an excellent essay by my very able former deputy in the VOA Polish Service, refugee journalist Marek Walicki, who previously had worked for RFE in Munich and in New York. Walicki and I shared Wierzyński’s negative assessment of VOA’s central bureaucracy, which Wierzyński described with some bitterness in the book.

For the next six years, I had worked for the Voice of America, and I consider this period the most frustrating in my life. The Voice of America was a [government] office (urząd), where one worked from 9 to 5. We had not very intelligent bosses, whose main concern was to keep their jobs, in the period when American international broadcasting was getting less and less money and Voice of America language services were being liquidated one after another. The bosses neither appreciated nor understood our work.[ref]Maciej Wierzyński, “Druga połowa życia,” in Wiesława Piątkowska-Stepaniak, ed., Autroportret zbiorowy – wspomnienia dziennikarzy polskich na emigracji z lat 1945-2002 (Opole: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Opolskiego, 2003), p. 178.[/ref]

Wierzyński wrote about the so-called annual “program reviews” at VOA as an “idiotic ritual,” in which “some journalistic rejects, incapable of working in foreign language services, evaluated programs in a foreign language, none of them knew.” At one of the program reviews, one such individual asked Wierzyński in a “reproving tone” why the Polish Service “broadcast dozens of interviews with some man named Karski?”

Jan Karski was, of course, one of the most famous Polish-Americans living at the time in Washington, D.C. A pre-WWII young Polish diplomat and a member of the anti-Nazi underground army in German-occupied Poland, Karski was an eyewitness of the Holocaust. He was once arrested and escaped from a Gestapo prison. During World War II, the anti-Nazi Polish resistance movement sent Karski to London and to Washington to warn British government leaders and U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt about the German extermination of Polish and other European Jews. President Roosevelt, whom Karski met at the White House on July 28, 1943, and most American and British journalists, with whom he had talked, ignored his appeals for taking drastic measures to save Jews.

These conversations with Karski, recorded when Wierzyński was in charge of the Polish Service, were extremely popular with listeners in Poland. They were later rebroadcast by Polish Radio.

But, as noted by Wierzyński, “at the Voice of America, a government broadcaster, what mattered was the title” [of the person being interviewed]. “They liked interviews with a [government] minister or a prime minister–but this Karski?” Jan Karski was for many years a professor of international relations at Georgetown University.

What Wierzynski’s American-born bosses also did not know was that in the 1950s, Karski helped a political refugee from Poland Seweryn Bialer, a future Columbia University professor, to expose during congressional hearings Stefan Arski (aka Artur Salman) as one of the most active anti-U.S. communist propagandists in Poland. From 1942 until 1947, Arski was employed by the Office of War Information (OWI) and the Voice of America before going back to Poland and joining the Communist Party. Arski was one of Howard Fast’s friends at the Voice of America and was in touch during the war with known Soviet intelligence agents.

In the conclusion of the section about VOA, Wierzyński wrote:

In 2000, I said farewell to the Voice with no regrets when the Polish Service as a separate entity was liquidated, and I was told to retire. While I do not regret [the loss of] the Voice [of America], I regret [the loss of Radio] Free Europe.

First Lady Hillary Clinton chatted briefly with Maciej Wierzyński during her visit to the Voice of America building in Washington, DC in June 1996. A photograph from his archive, which appears in the book published in Poland, shows them shaking hands. In 2013, when Clinton was the Secretary of State, she called the Voice of America’s parent federal agency “practically defunct”–a view shared by many of the former VOA broadcasters who had escaped from communism.

The new name of the Broadcasting Board of Governors is the U.S. Agency for Global Media (USAGM). This government agency is now even more dysfunctional and scandal-ridden than it was during Wierzyński’s tenure at the Voice of America. Some of VOA programs in recent years glorified Fidel Castro, Che Guevara, and Angela Davis. They have been almost reminiscent of the time when fellow travelers, Howard Fast and Stefan Arski, hired by the first VOA director John Houseman, broadcast pro-Soviet propaganda and called for the establishment of Soviet-friendly regimes in East-Central Europe.

Maciej Wierzyński wrote in the conclusion of his essay that also important for journalists is “being ready to critically assess not just other people, but also their own profession, and to reflect on the state of the media and their role in the country’s political and social life.”