Truman’s ‘Campaign of Truth’ at Voice of America Part I: Countering Soviet Propaganda Abroad and at Home

In a new multipart series presenting many primary sources, the Cold War Radio Museum is looking at President Harry S. Truman’s “Campaign of Truth” (1950-1952) against Soviet propaganda and at problems with its implementation at the U.S. government-run Voice of America (VOA) between April 1950 and the end 1952. The difficulties the Truman Administration encountered in the early phases of the Cold War are not dissimilar to those facing U.S. taxpayer-funded international media today in responding to the Russian government’s anti-American and anti-democratic propaganda. In the “Campaign of Truth” series, we analyze causes of successes and failures of early Cold War U.S. information programs abroad as well as Truman Administration officials’ attempts to influence U.S. public opinion and VOA officials’ “claims of broadcasting success which are supported by impressive but sometimes misleading statistics,” as the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Foreign Relations concluded in 1953 in a bipartisan report.[ref]83rd Congress, U.S. Senate, Committee on Foreign Relations, Report No. 406, Overseas Information Programs of the United States, June 15, 1953. Page 30. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.35112102288521?urlappend=%3Bseq=1574[/ref]

Introduction

By Ted Lipien for Cold War Radio Museum

Wilson M. Compton, former Washington State College President with a PhD in Economics from Princeton and later a Republican lobbyist in Washington D.C. for the lumber industry, was in 1952 President Truman’s choice to run the newly reorganized International Information Administration (IIA) within the Department of State, which included the Voice of America (VOA), the U.S. government’s tax-funded official international broadcaster. Soon after taking up his job, Dr. Compton published with the help of State Department speechwriters an article titled “Waging the Campaign of Truth,” describing the planned expansion of the U.S. Information and Educational Exchange Program, as he put it, “to safeguard American security.”[ref]Wilson M. Compton, Administrator, International Information Administration, the Department of State, Field Reporter, July-August 1952, p. 10. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.d0004680286?urlappend=%3Bseq=4.[/ref] He was the senior State Department official in charge of not only the Voice of America but also all of the Department’s other information and cultural and educational outreach and exchange programs. Compton had no background in either media operations or foreign relations and only a limited experience in federal government service, but he was a Republican who could help blunt his own party’s growing criticism of the Democratic Truman Administration’s response to the Soviet propaganda offensive and communist military aggression in Korea.[ref]David F. Krugler, The Voice of America and the Domestic propaganda Battles (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2000), pp. 172-173.[/ref]

At the State Department, Truman put Compton in charge of implementing the “Campaign of Truth”–a multi-faceted U.S. government’s international information policy unveiled in a foreign policy speech on April, 20, 1950 to members of the American Society of Newspaper Editors as the answer to harsh Soviet propaganda attacks on the United States and its allies.[ref]Harry S. Truman, “Address on Foreign Policy at a Luncheon of the American Society of Newspaper Editors,” April 20, 1950. National Archives, Harry S. Truman Library and Museum. https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/library/public-papers/92/address-foreign-policy-luncheon-american-society-newspaper-editors.[/ref] Truman’s “Campaign of Truth” address was designed to inspire journalists, including Voice of America’s federal employees of the Department of State broadcasting at the time to the world in multiple languages from VOA studios in New York, to offer a stronger and more effective resistance to Soviet propaganda and to communist influence. “Everywhere that the propaganda of the Communist totalitarianism is spread, we must meet it and overcome it with honest information about freedom and democracy,” Truman said. He also alluded to the media’s criticism of his foreign policy and indirectly to criticism of the Voice of America. “Foreign policy is not a matter for partisan presentation,” Truman said as he outlined his administration’s plan to resist communism and its propaganda with the “Campaign of Truth.”

President Truman’s ‘Campaign of Truth’ Address, April 20, 1950

In a democracy, foreign policy is based on the decisions of the people.

One vital function of a free press is to present the facts on which the citizens of a democracy can base their decisions. You are a link between the American people and world affairs. If you inform the people well and completely, their decisions will be good. If you misinform them, their decisions will be bad; our country will suffer and the world will suffer.

You cannot make up people’s minds for them. What you can do is to give them the facts they need to make up their own minds. Now that is a tremendous responsibility.

Most of you are meeting that responsibility well–but I am sorry to say a few are meeting it very badly. Foreign policy is not a matter for partisan presentation. The facts about Europe or Asia should not be twisted to conform to one side or the other of a political dispute. Twisting the facts might change the course of an election here at home, but it would certainly damage our country’s program abroad.[ref]Harry S. Truman, “Address on Foreign Policy at a Luncheon of the American Society of Newspaper Editors,” April 20, 1950. National Archives, Harry S. Truman Library and Museum. https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/library/public-papers/92/address-foreign-policy-luncheon-american-society-newspaper-editors.[/ref]

‘The Ship with a Cargo of Truth’

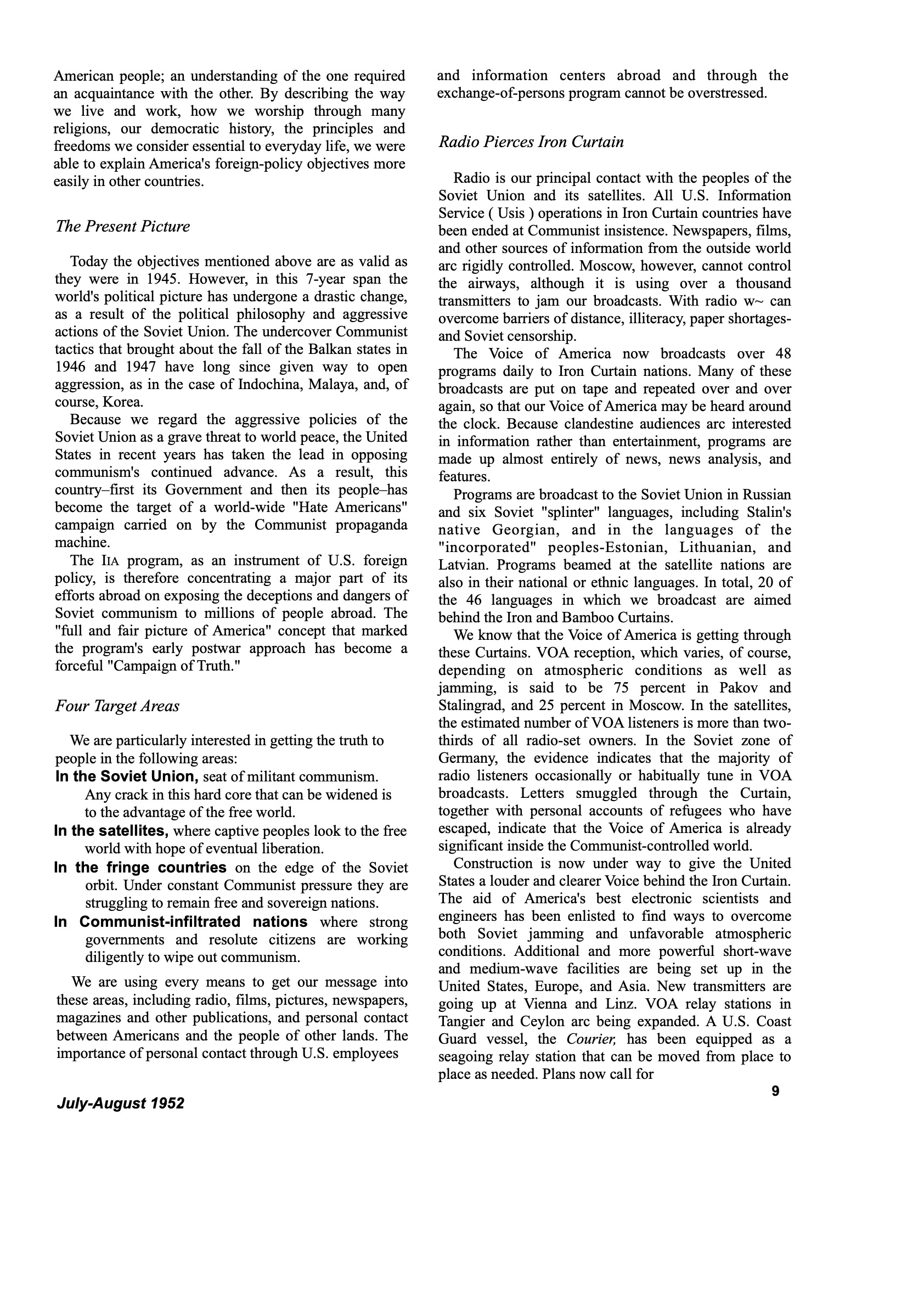

Compton’s 1952 article had a section titled “Radio Pierces Iron Curtain,” but offered no special insights into what kind of programs listeners behind the Iron Curtain expected from the Voice of America. He and his speechwriters would be unlikely to consult low-ranking VOA foreign-language broadcasters who recently fled from communism, while at Radio Free Europe (RFE), which started broadcasting in 1950 under the then secret umbrella of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), such refugee journalists played key roles in charge of planning programs together with the American management. Most of Compton’s presentation was devoted to traditional State Department-run information, cultural and educational exchange programs conducted outside the communist block. Communist regimes had already prevented U.S. embassies in their countries from carrying out most of their normal public diplomacy activities, leaving radio, as Compton noted, as “principal contact with the peoples of the Soviet Union and its satellites,” but there was no particularly strong focus in his article on greatly expanding Voice of America broadcasts to East-Central Europe, the Soviet Union or communist-ruled China. He had to know but could not say publicly that Radio Free Europe would fill the gap, at least in Eastern Europe. State Department employees were probably quite happy that they could use extra money obtained for the “Campaign of Truth” on their non-broadcasting public diplomacy activities outside the communist block.

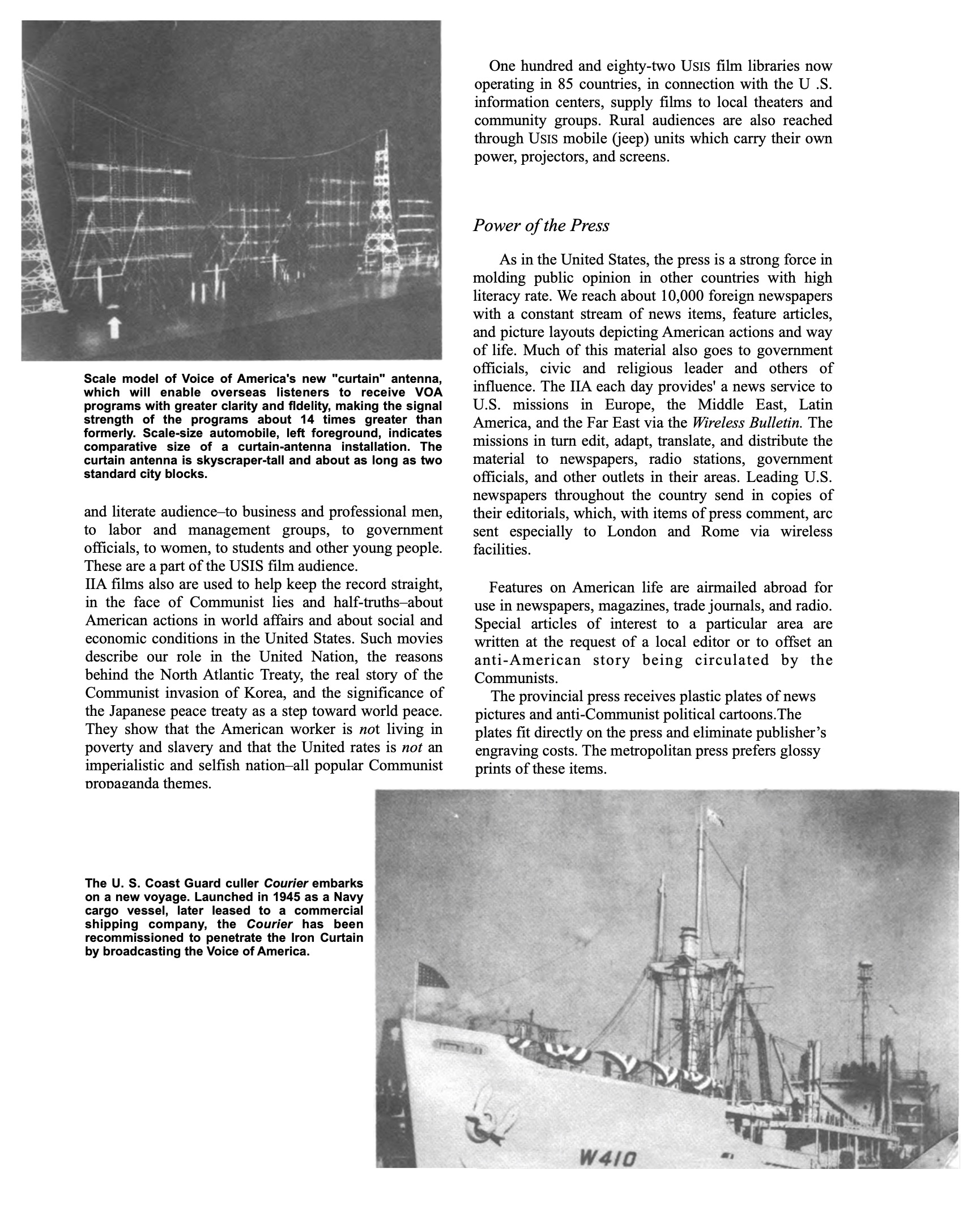

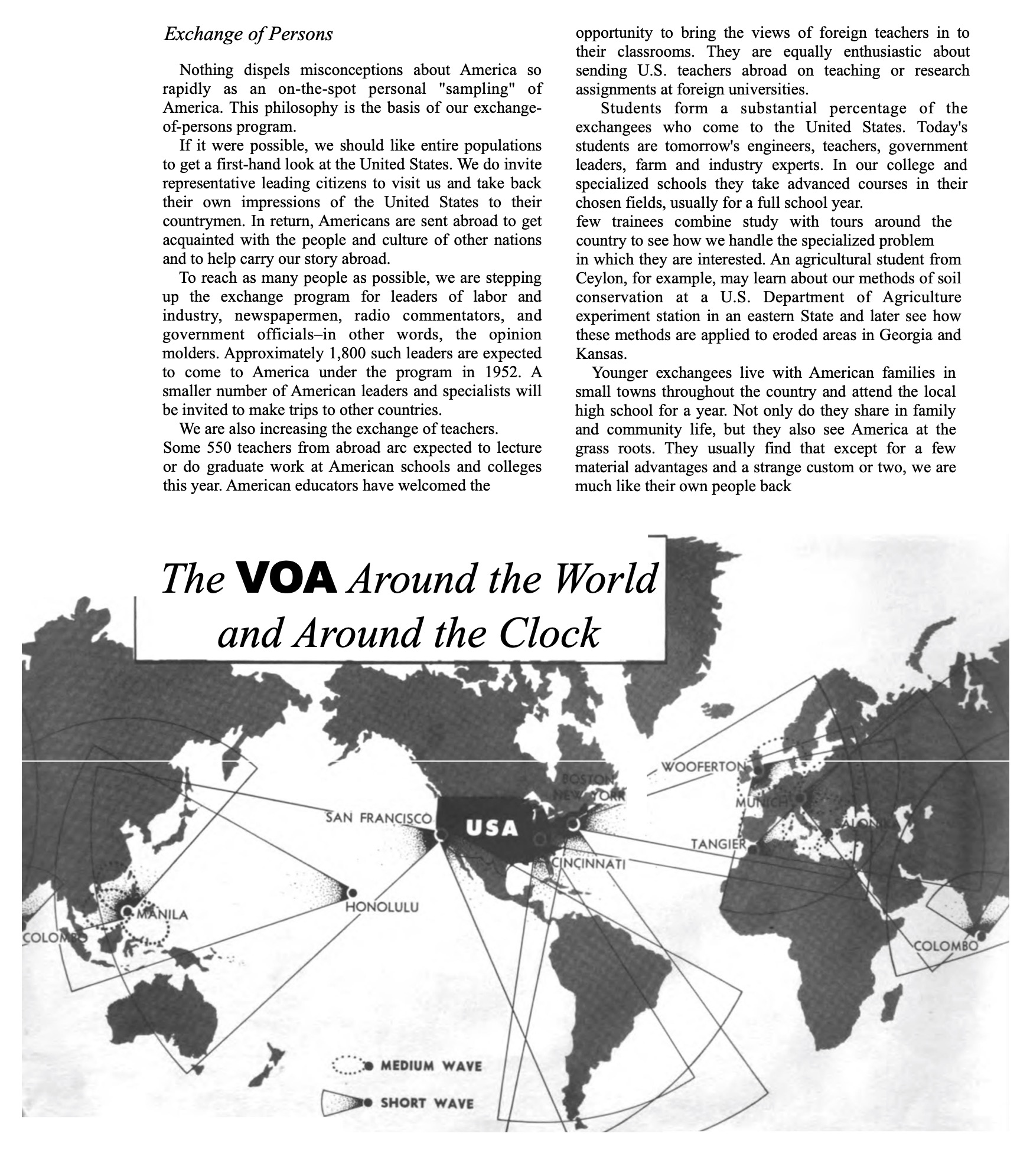

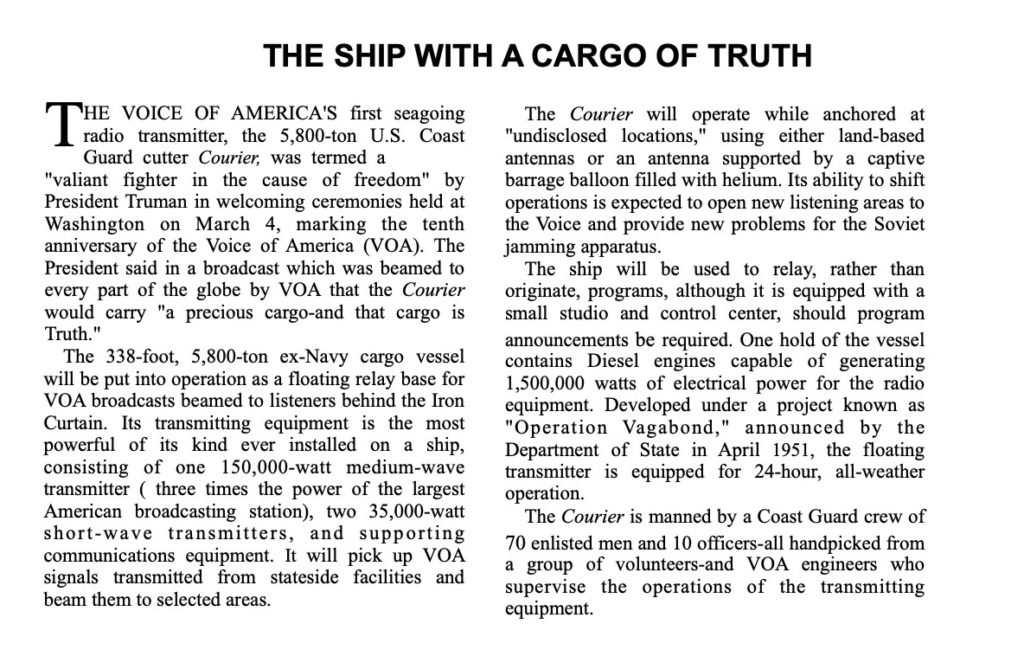

Not too long after Truman’s “Campaign of Truth” address, the Voice of America engineering department and its mixed senior management of State Department diplomats and former American private sector media executives and journalists made an unusual proposal that a Coast Guard ship, renamed the Courier, be used as a mobile radio transmitter. The Truman Administration responded to Soviet propaganda during the early stages of the Cold War by asking Congress for money to increase the power of Voice of America’s shortwave and medium wave radio transmissions. An important part of the plan was the use of the USCGC Courier WAGR/WAT-410 as a “mobile” VOA transmitter to overcome Soviet jamming of Western radio stations. The State Department and President Truman must have been assured by VOA engineers that a Coast Guard ship would be uniquely suitable for this purpose. But perhaps not entirely convinced of VOA’s capabilities, the Truman White House and senior State Department leaders also semi-secretly supported the creation of Radio Free Europe and later Radio Liberty (RL) as alternative U.S. government-funded broadcasters based in West Germany and operating outside of the Washington federal bureaucracy with a much greater independence and flexibility.

President Truman repeated many of his “Campaign of Truth” themes in an internationally broadcast address from the U.S. Coast Guard cutter Courier on March 4, 1952, when the ship docked in Washington D.C. “We must use every means to combat the propaganda of slavery,” President Truman said in sending the ship on its mission.[ref]”Cargo of Truth,” address by Harry S. Truman, President of the United States, March 4, 1952, Department of State Publication 4525. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951d03597173k.[/ref]

Wilson Compton’s article, which had a small section about the Courier, did not mention Radio Free Europe or plans for launching Radio Liberty to target audiences in the Soviet Union. RFE eventually did much of the work that most Americans familiar with international broadcasting and many Truman Administration officials expected in the late 1940s to be done by the Voice of America, but VOA lost its chance during the Truman Administration to become the main broadcaster of the United States for countries in East Central Europe and in the Soviet Union.

‘Waging the Campaign of Truth’

At the time of its launching in April 1952, the Courier was called “The Ship With A Cargo of Truth.” It was not the best chosen ship to carry a powerful radio transmitter. The ship’s problematic design, approved by Voice of America engineers, was investigated in 1953 by two Senate subcommittees. Both investigations, however, covered much broader and more serious problems with VOA management and programming. One was led by Senator Bourke B. Hickenlooper (R-IA), a senior Republican member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, and the other by Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-WI) who was eventually censored by the Senate for his reckless accusations of pro-communist disloyalty against innocent Americans. The Courier could not move quickly from place to place, as President Truman suggested, but he observed correctly that “Its significance lies in the fact that it will carry on the fight for freedom in the field where the ultimate victory has to be won–that is, in the minds of men.”

Part of the victory had to be won in the United States and in other democratic nations, where the Courier fulfilled its role as an important public diplomacy initiative and a domestic public relations attempt by those Truman Administration officials who together with the President took the Soviet threat seriously. They were sending a signal not only to supporters of the Soviet Union in the West, but also to Republicans who criticized the President, mostly unjustly, for being soft on communism. Until President Reagan, Truman was perhaps the most anti-communist U.S. president. With the visit to the Courier and his speech he was also sending a signal to some officials in his own administration, including the Voice of America, who were still reluctant in 1950 to condemn communism and the Soviet government. The “Campaign of Truth” and a high-visibility given by the White House to sending the Courier on its mission by the President himself was a wake-up call for the State Department and Voice of America government bureaucracy that they should make VOA programs more hard-hitting against communism.

President Truman Visits the Courier, March 4, 1952

Cargo of Truth Address

VOA eventually did sharpen its program content and tone after much prodding and criticism in the U.S. Congress and media but not without some initial resistance and a considerable delay. The resistance was far from universal. Some at VOA, especially among employees hired during the Roosevelt Administration, did not approve of a harder stance against Russia; others, especially recent refugees from fascism and communism who knew from their own experience that the two totalitarianisms shared much in common in their disdain for freedom and human rights, cheered and lobbied for a change of programming.

‘Sharpened Program Content’

Before the 1952 launch of the transmitter-ship but after President Truman’s “Campaign of Truth” speech, Secretary of State Dean Acheson said in his semiannual report to Congress on the International Information and Educational Exchange Program for the period July 1 to December 31, 1950, that “Operationally, launching of the Campaign of Truth was reflected at the outset more in sharpened program content and specialized radio treatment than in marked increases in broadcast operations.”[ref]Dean Acheson, U.S. Secretary of State, “Launching the Campaign of Truth–First Phase: Sixth Semiannual Report of the Secretary of State to Congress on the International Information and Educational Exchange Program, July 1 to December 31, 1950,” Department of State Publication 3479, December 1951, p. 3. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951d03562370p?urlappend=%3Bseq=8.[/ref] Acheson indirectly agreed with critics that earlier VOA programming to the Soviet Union was not well-planned to meet the Soviet propaganda challenge. Jamming was not the main factor for the need to change VOA’s programming policy. The Stalinist regime was just as murderous in 1947, when the VOA Russian broadcast was finally started, as it was in the second half of 1950, the period covered by Acheson’s report to Congress.

In the broadcasts to Eastern Europe, greater program variety was introduced; more liberal use was made of anti-Communist political satires and exposés, and of the documentary and dramatized technique.

The systematic jamming of VOA’s Russian broadcasts greatly influenced both their content and format. Music and dramatizations were eliminated, and the salient portions of the programs were repeated around the clock. Later in the period, when a partial neutralization of the Soviet jamming effort was achieved, some of the dramatized material was restored. An increasing number of Soviet DP’s came to the microphones of VOA to tell their story.[ref]Dean Acheson, U.S. Secretary of State, “Launching the Campaign of Truth–First Phase: Sixth Semiannual Report of the Secretary of State to Congress on the International Information and Educational Exchange Program, July 1 to December 31, 1950,” Department of State Publication 3479, December 1951, p. 4. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951d03562370p?urlappend=%3Bseq=11.[/ref]

Sixth Semiannual Report to Congress

At least, Secretary Acheson admitted that VOA’s program content was previously not sufficiently sharp, but progress to resolve the problem was not quick within the government bureaucracy. Whistleblowers and members of Congress continued to report questionable programming at VOA for at least two more years. The Voice of America improved its radio broadcasts to the Soviet Block later in the 1950s but did not expand them substantially, except for Russian-language programs. Even adding extra time to VOA Russian broadcasts took several years since their inception in 1947.

The State Department personnel took advantage of its own Courier-related public relations campaign in the United States focused on fighting communism with radio broadcasting to also generate support for their other public diplomacy activities, most of them in Western countries and in the Third World. Millions of dollars went toward building new radio transmitters, but there were no spectacular new VOA programming initiatives targeting the Soviet Block. Secretary Acheson was able, however, to report to Congress in 1952 on new “program originations within the shadow of the Iron Curtain from the new Munich programming center with a daily Polish-language broadcast.”[ref]Dean Acheson, U.S. Secretary of State, “Launching the Campaign of Truth–First Phase: Eight Semiannual Report of the Secretary of State to Congress on the International Information and Educational Exchange Program, July 1 to December 31, 1951,” Department of State Publication 4575, December 1951, p. 1. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951d03562372l?urlappend=%3Bseq=6.[/ref] These were modest additions although with substantially improved reporting on human rights violations behind the Iron Curtain. It was far less than what was needed and what audiences wanted from VOA. The new VOA program to Poland was only 15 minutes long.

The Voice of America center in Munich opened in late 1951 and eventually included VOA broadcasters from several countries who initiated short programs based partly on interviews with refugees from behind the Iron Curtain in an apparent attempt to compete with Radio Free Europe, which had much more airtime and more relevant news. One of VOA’s broadcasters in Munich, Zbigniew Brydak (aka Stefan Michalski), turned out to be a Polish communist spy. RFE refused to hire him, but he briefly worked for VOA as a commentator and announcer. He did not have any editorial or managerial functions at the Voice of America in Munich, but before coming to West Germany he was, according to former RFE/RL journalist and former VOA Polish Service deputy chief Marek Walicki who knew him, an agent-provocateur for the communist regime who denounced a number of Poles to the communist secret police who were then tortured and executed. He later returned to Poland and joined former wartime Voice of America editor Stefan Arski (aka Artur Salman) in writing articles and producing anti-U.S. propaganda broadcasts.[ref]See in Polish Marek Walicki’s Z Polski Ludowej do Wolnej Europy (Warszawa: Bellona, 2018), pp. 170-182. RFE had several more communist agents working for them, also usually in minor positions without any significant editorial influence. Communist regimes perceived the two stations as much more dangerous to them than VOA and concentrated their spying activities on them.[/ref] Arski was one of many pro-communist wartime VOA journalists, including VOA’s first chief English-language news writer and editor Howard Fast, a best-selling American author who in 1953 received the Stalin Peace Prize.[ref]Cold War Radio Museum, “Created 70 years ago, Stalin Peace Prize went in 1953 to former Voice of America chief news writer Howard Fast,” December 21, 2019. https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/created-70-years-ago-today-stalin-peace-prize-went-in-1953-to-former-voice-of-america-chief-news-writer-howard-fast/.[/ref] Arski, whose legal name at the Voice of America was Artur Salman, remained in his VOA job being employed by the State Department until 1947. Unlike Brydak at the VOA Munich Center, Arski had some managerial and editorial role in New York during and after the war in shaping VOA programs to Poland.[ref]Ted Lipien, “Voice of America Polish Writer Listed As His Job Reference Stalin’s KGB Agent of Influence Who Duped President Roosevelt, Cold War Radio Museum, February 12, 2020. https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/voice-of-america-polish-editor-listed-stalins-kgb-agent-of-influence-as-job-reference/.[/ref] The VOA Munich center was closed after operating for eight years.

Fortunately for the United States and for radio listeners behind the Iron Curtain, Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty did much of the heavy lifting in countering communist propaganda from their studios in Munich and did it well, but the Truman Administration and later the Eisenhower Administration could not take publicly full credit for the success of such surrogate broadcasting secretly managed and funded by the U.S. government through the Central Intelligence Agency. The State Department and the Voice of America were prohibited by the 1948 Smith-Mundt Act (Public Law 80-402)—a compromise bipartisan legislation signed by President Truman on January 27, 1948, to provide authority and funding largely for the expansion of State Department’s non-broadcasting information, cultural and educational exchange activities abroad—from using any of their taxpayer-funded programs to target Americans with domestic propaganda. This provision was a result of considerable concern on Capitol Hill that the Roosevelt Administration had misused its wartime information programs for domestic partisan propaganda and also allowed the Voice of America to fall under the influence of Soviet sympathizers, which gave an advantage to Soviet Russia in deceiving Americans and world opinion during and for a few years after the war.

Origins of the 1948 Smith-Mundt Act

The 1948 Smith-Mundt Act

The 1948 Smith-Mundt Act, known under its full name as the “United States Information and Educational Exchange Act of 1948,” only gave legislative authority for the information program of the State Department “To promote a better understanding of the United States in other countries and to increase mutual understanding between the people of the United States and other countries.” Under the new Public Law 402, the Truman Administration could no longer distribute Voice of America news and other program materials in the United States but together with the State Department could use public events, such as the commissioning of the Courier, to announce its policy goals and to brag about its successes to the American public. Even with a weak programming to the communist world, VOA was still an important source of information for listeners who had few other options to get uncensored news. Voice of America journalists who were not afraid to criticize Stalin had good reasons to be proud of their work, but leaders in charge of VOA often tried to mislead Congress with exaggerated claims of successes to cover up their failure to reform and expand radio programming as quickly and as fully as the challenge from communism and Soviet propaganda required.

Radio Free Europe had more reasons to be proud of its work for listeners in Eastern Europe but conducted its own somewhat deceptive public relations campaign in the United States through the so-called “Crusade for Freedom,” which implied that RFE was supported entirely by private donations. “Crusade for Freedom” magazine ads and public service radio commercials appealed to Americans to give money to RFE by making them believe that they were the only source of support for the broadcaster. In reality, almost all of the station’s money came from the U.S. government through the CIA. Congress ended the secrecy and the CIA’s involvement with the station in 1971.

RFE Crusade for Freedom

Some of the secrecy, especially in connection with CIA officers assigned in the early years to manage RFE, was believed to be necessary to preserve journalistic credibility and U.S. government’s deniability to allow RFE and later RL journalists to engage in harsh criticism of communist regimes and their leaders, but former RFE officials later admitted that it would have been better to be open about the real source of the station’s funding. In contrast, many Voice of America officials and some of its former journalists went into great lengths to make sure that VOA programming, personnel and managerial mistakes during the Cold War would be forgotten and never discussed.

On Balance

On balance, however, Voice of America’s contributions to winning the Cold War vastly outweighed any failures of its leadership and some journalists, but only because it became a frequent target of congressional and other public scrutiny already during World War II. The Courier did not perform as well against Soviet jamming as VOA engineers who had mishandled the project in its design stage claimed that it would, but it performed a useful publicity role in alerting Americans to the need to respond to Soviet propaganda. Over the years, its Coast Guard crews and VOA technicians helped to deliver radio programs to several communist-ruled countries and some Third World countries in the Middle East and Asia that could have come under Moscow’s influence. The ship helped to win the Cold War, even though some U.S. government officials misled the American public with exaggerated promises of its radio broadcasting capabilities. By becoming a source of a minor public controversy, the Courier also helped to focus the attention of the Truman Administration and members of Congress of both parties on more serious problems at the Voice of America that needed to be addressed and solved early in the Cold War to meet the growing threat of communism.