Voice of America Polish Writer Listed As His Job Reference Stalin’s KGB Agent of Influence Who Duped President Roosevelt

By Ted Lipien for Cold War Radio Museum

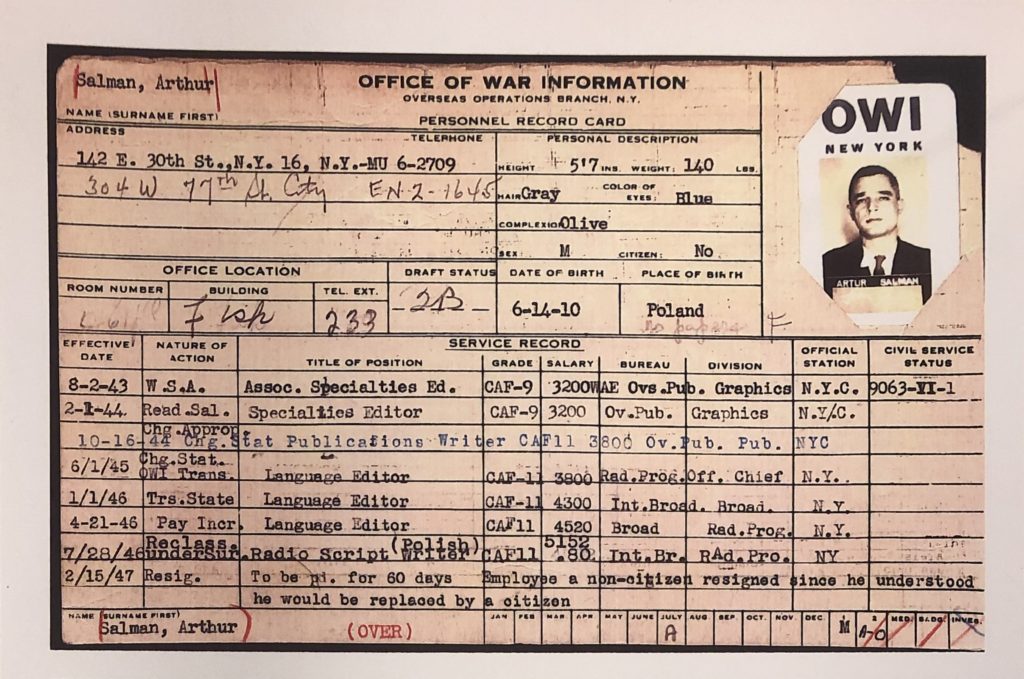

One of many pro-Soviet journalists working during World War II and, in some cases for a few years after the war, at the U.S. government-run Voice of America (VOA) was Artur Salman, better known under his pen name Stefan Arski. Before and during his employment at the Office of War Information (OWI), starting from August 1943, and later at the U.S. State Department until February 1947, Salman-Arski was in contact with a Marxist economist Oskar R. Lange who was one of Stalin’s most important KGB-supervised agents of influence in the United States tasked by Moscow with getting President Roosevelt to agree to Soviet control over Poland after World War II.

Salman-Arski’s name does not appear in any of the most read books about Voice of America’s history[ref]Alan L. Heil, Jr., Voice of America: A History (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003).[/ref] or in promotional materials produced by VOA’s public relations department in the U.S. Agency for Global Media (USAGM),[ref]VOA Public Relations, “VOA Through the Years,” April 3, 2017, https://www.insidevoa.com/a/3794247.html.[/ref] the current federal parent agency for VOA. These books and agency promotional materials also do not mention another famous former Voice of America communist, VOA’s first chief news writer and editor Howard Fast, who was the 1953 Stalin International Peace Prize winner.

Today’s Voice of America journalists, as well as other Americans, have been protected for years from learning about Salman-Arski and discovering his link to a World War II KGB influence operation targeting, among others, senior U.S. government officials. They also do not know about Arski’s later career as an anti-American communist propagandist. The KGB-overseen attempt to dupe President Roosevelt and many other Americans that Stalin was not a mass murderer similar to Adolf Hitler was initially phenomenally successful. Stefan Arski contributed to it, first in OWI propaganda pamphlets and VOA broadcasts, and later as a journalist and propaganda writer serving the communist regime in Poland.

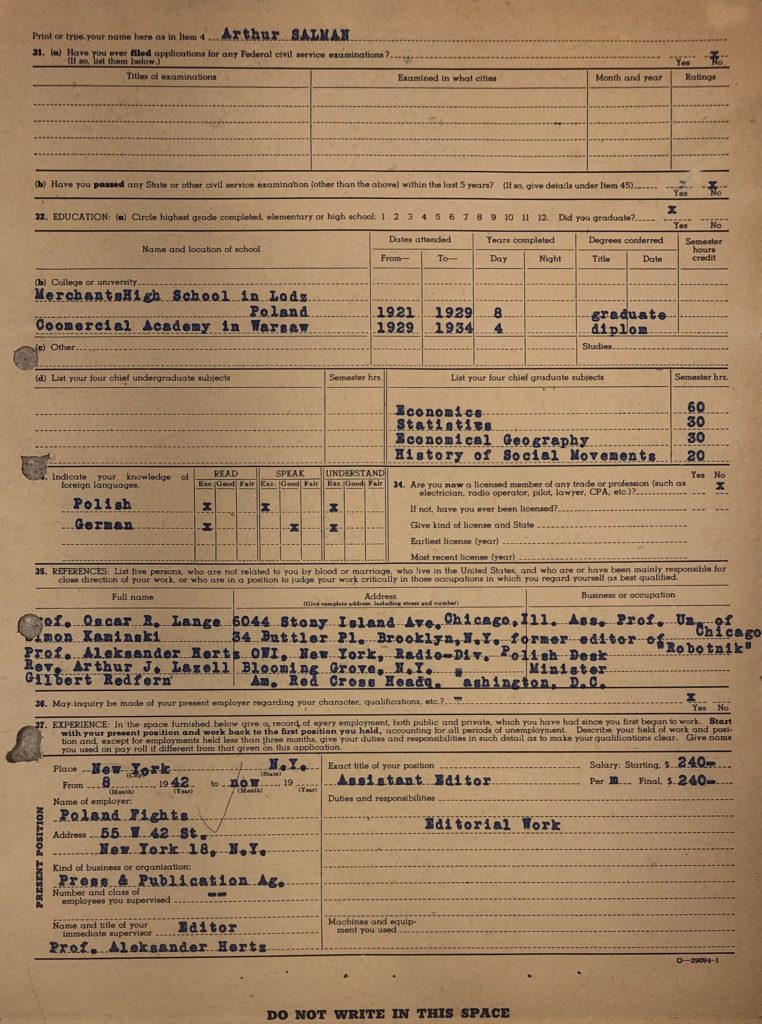

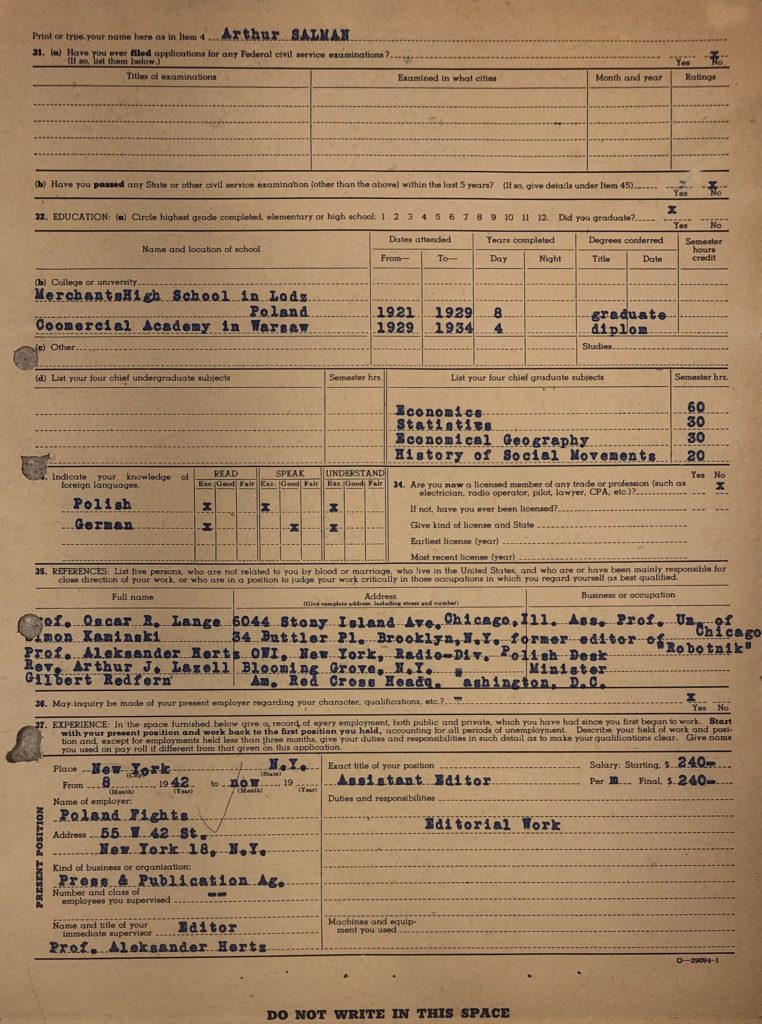

Artur Salman (Stefan Arski) and Oskar Lange met in Chicago in 1941[ref]Krzysztof Groniowski, “‘Poland Fights’ : 1941-1946,” Kwartalnik Historii Polskiej, XXIX 2, 1990.[/ref], they exchanged letters and both had meetings with a known KGB communist agent in the United States Bolesław (Bill) Gerbert. Salman-Arski listed Lange as a number one reference on his 1943 application for a federal government job at the Office of War Information (OWI) which ran Voice of America radio broadcasting during World War II. Initially hired to produce anti-Nazi propaganda, Artur Salman also wrote socialist pamphlets for Americans with the approval of his U.S. government supervisors, in which he and other OWI journalists called for a Marxist economy in post-war Poland and a government friendly to Moscow. He later worked for the U.S. State Department as a writer and editor of Voice of America radio broadcasts until his resignation in early February 1947 and his eventual return to Poland to become a propagandist for the Soviet-imposed communist regime.

Before the war, Salman-Arski and Oskar Lange were both supporters of Marxist socialism, but not yet in favor of how it was being implemented by Stalin in the Soviet Union. Both men were born and educated in Poland. Lange emigrated to the United States before the Second World War and worked as an assistant professor at the University of Chicago. In 1943, Lange became a naturalized U.S. citizen and at about the same time decided to support Stalin and his plans for Eastern Europe. He was a key figure in a KGB influence operation designed to convince Americans that Stalin was not a dictator, but a progressive leader who appreciated the value of religious freedom and democracy. The disinformation campaign in which Lange participated was described in a 1944 Washington Post op-ed as “a political burlesque, staged and directed by capable Soviet agents” for propaganda purposes. Officials in the Office of War Information and Voice of America journalists, however, saw Soviet propaganda exactly as the KGB wanted to present it to Americans and world public opinion. To these left-leaning U.S. government officials and journalists, it was a sign of Stalin’s goodwill, and they were eager to highlight it as such in their own pro-Soviet propaganda. They heavily promoted such misleading and false information since the first VOA broadcast to Europe in 1942 while censoring out negative information about Stalin and the Soviet Union in VOA newscasts.

The KGB operation also targeted the Polish-American community, which was overwhelmingly religiously Catholic, anti-Soviet and anti-communist. With advice from Bolesław Gebert, the KGB wanted to divide Polish-Americans and perhaps get some to change their attitude toward Stalin’s plans for Poland. At the invitation of the Soviet government and with support from the Roosevelt White House, Professor Lange, a recently naturalized U.S. citizen, and Rev. Stanislaus Orlemanski, a radical Polish-American Catholic priest from Springfield, Massachusetts who was born in the United States, traveled to Moscow in April and May 1944 for an unusual meeting with Joseph Stalin bound to attract media attention. The KGB planned the trip to convince President Roosevelt, U.S. media, Polish-Americans, and Americans in general that the Soviet dictator was a supporter of religious freedom and democracy. Bolesław Gebert, a paid KGB agent in the United States who was in contact with both Lange and Salman-Arski, suggested that Lange would be suitable for such a trip and could play a role in a pro-Soviet government in post-war Poland. Stalin agreed and proposed the idea for the trip to the U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union Averell Harriman, who passed it on to Washington. Years later, Gebert wrote in his official memoirs published in Poland, Z Tykocina za ocean (“From Tykocin to Beyond the Ocean”) that he and Lange “were of the same opinion that in the interest of Polish democracy, there must be a widespread activity in the United States, not only among Polish-Americans but within the American society in general. We were both in agreement that the fate of the Polish nation is linked to the USSR.” His reference to “Polish democracy” was particularly ironic considering how many Poles were murdered by the Stalinist regime in Poland. It also showed his knowledge of using propaganda and its language, which the KGB did with great success in America during the war with the help of naive politicians and journalists.

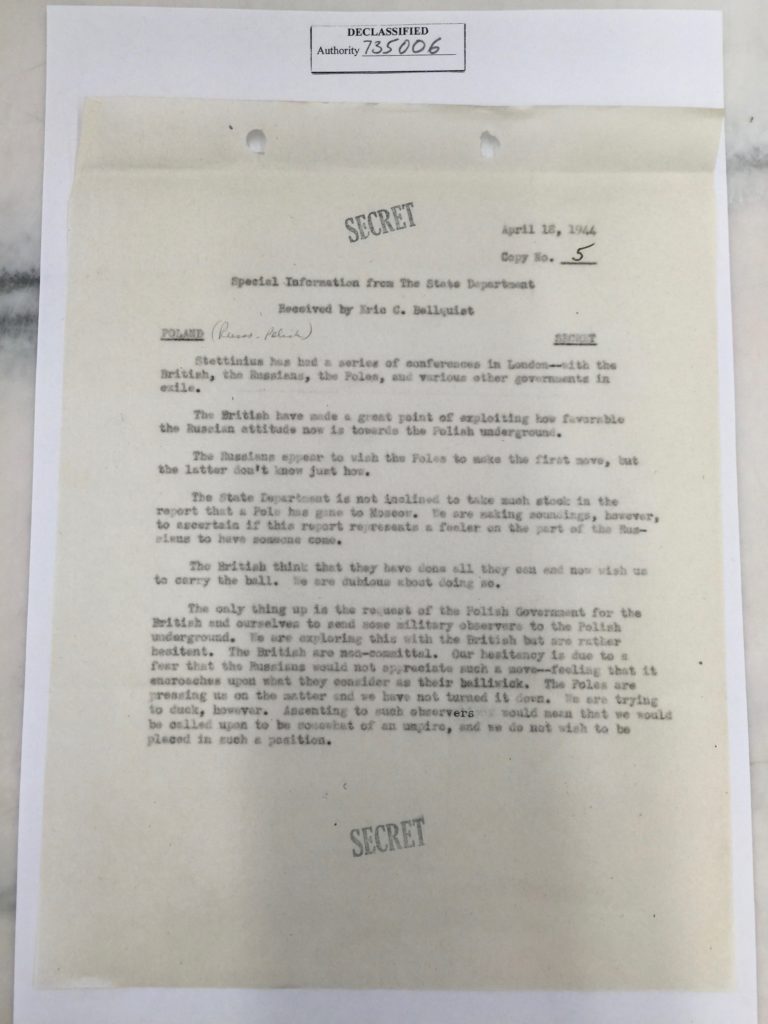

While the U.S. State Department was generally opposed to sending pro-Soviet Polish-Americans to Russia, the trip won the approval of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Lange and Orlemanski received U.S. passports, and the Pentagon facilitated their flight to Moscow. The strongly pro-Moscow Voice of America broadcasters immediately wanted to exploit the trip for propaganda purposes, to show how reasonable the Soviet leader was on the question of the future of Poland and religious freedom. But when the Catholic Church hierarchy in the United States, Polish-American leaders, and various members of the U.S. Congress, many of them Democrats, condemned the mission as a propaganda stunt designed to deceive American public opinion, President Roosevelt, apparently concerned about losing the Polish-American vote for himself and the Democratic Party, withdrew his public support for the trip, although he continued to express his approval for it in private White House meetings. In public meetings, including those with leaders of the Polish-American community, he continued to deny that he had already agreed to Stalin’s demands about Poland and used propaganda to mislead Polish-American voters. Just before the 1944 presidential election, he met at the White House with a group of Polish-American leaders. The meeting was held in front of a big map showing Poland’s pre-war frontiers, even though a year earlier he had promised Stalin Poland’s eastern territories and effectively assigned Poland and other nations in Central and Eastern Europe to become part of the Soviet empire. Polish-American newspapers published photographs from the White House meeting. Over 90% of all Polish-Americans voted for FDR in 1944.

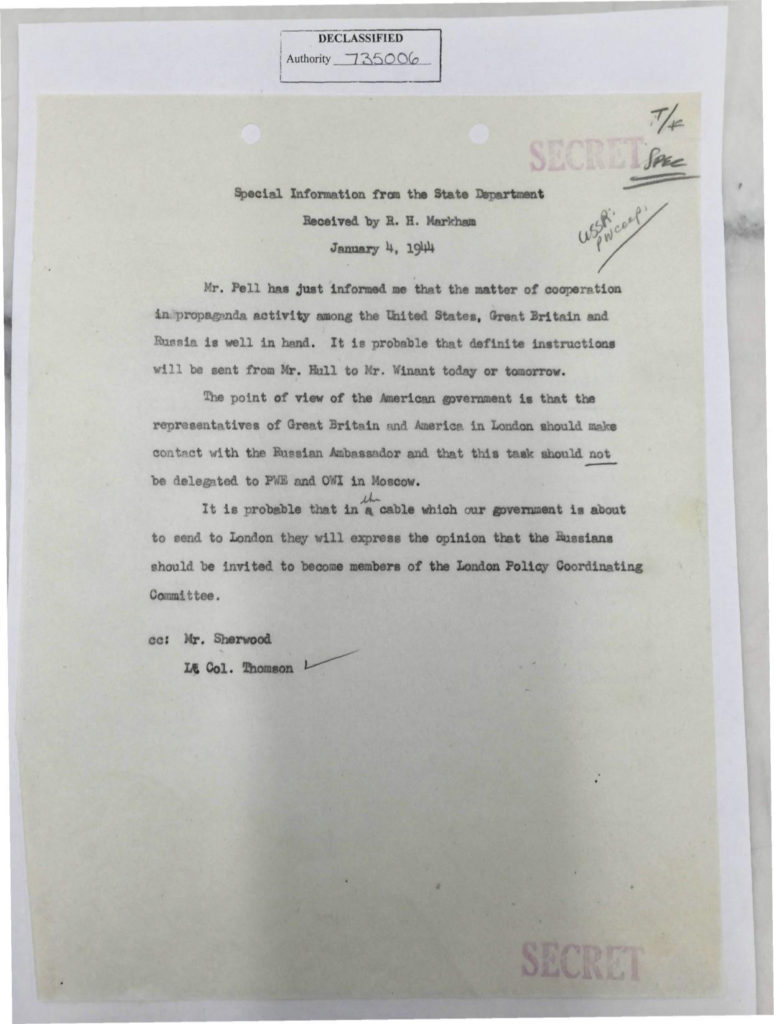

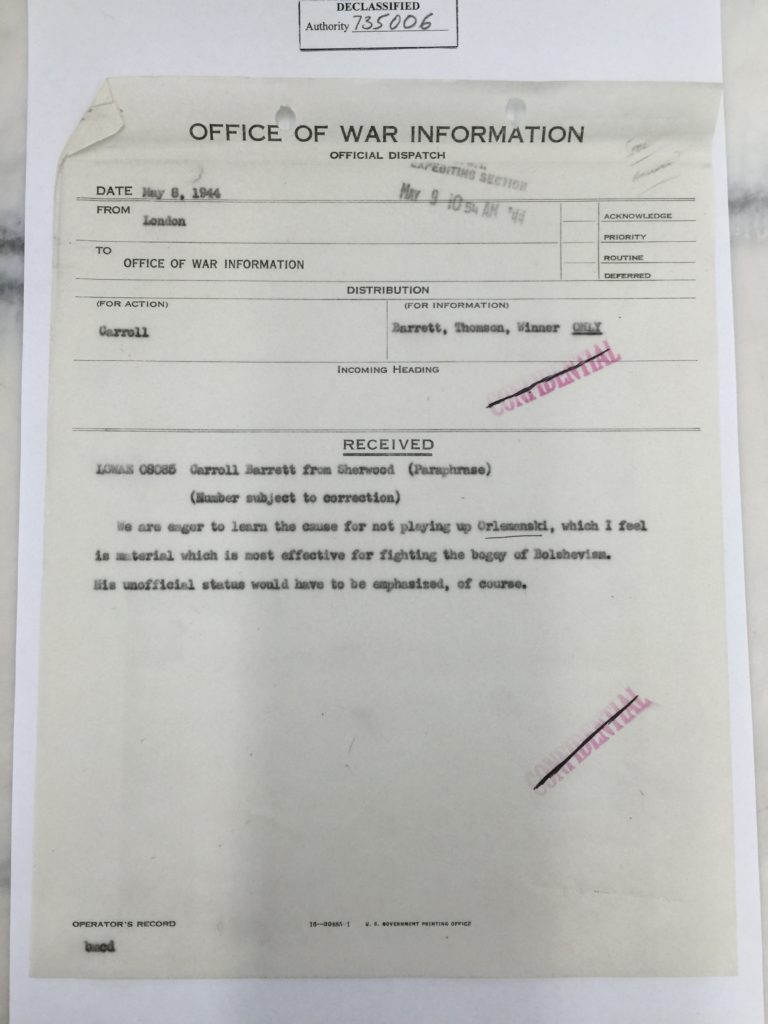

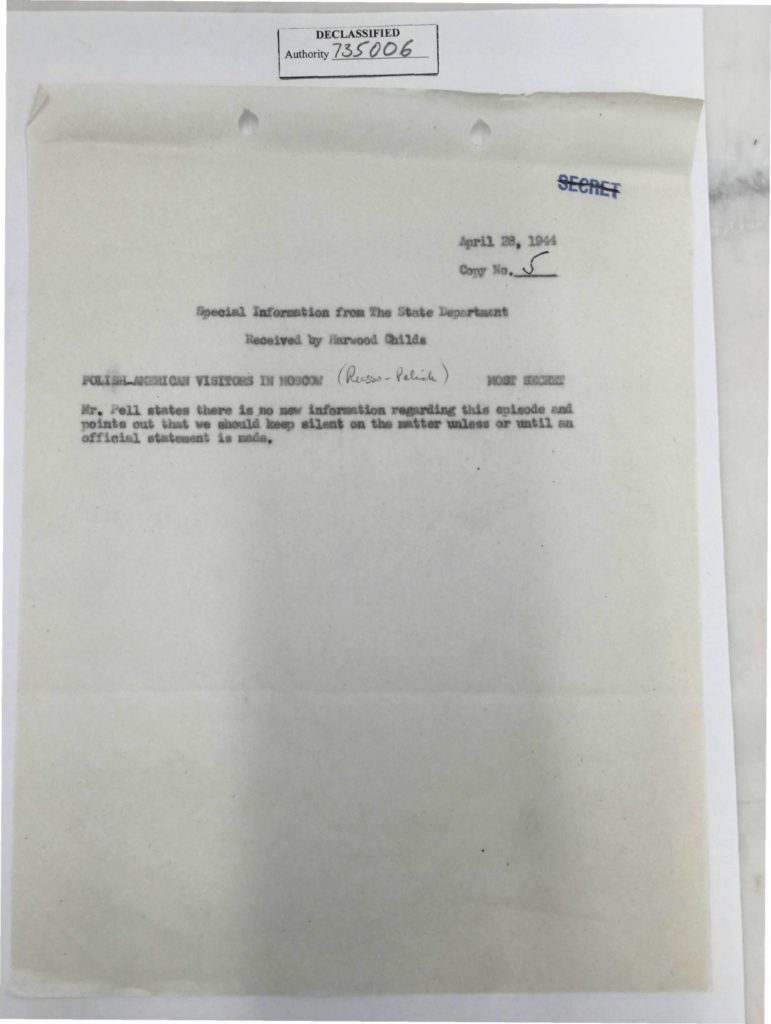

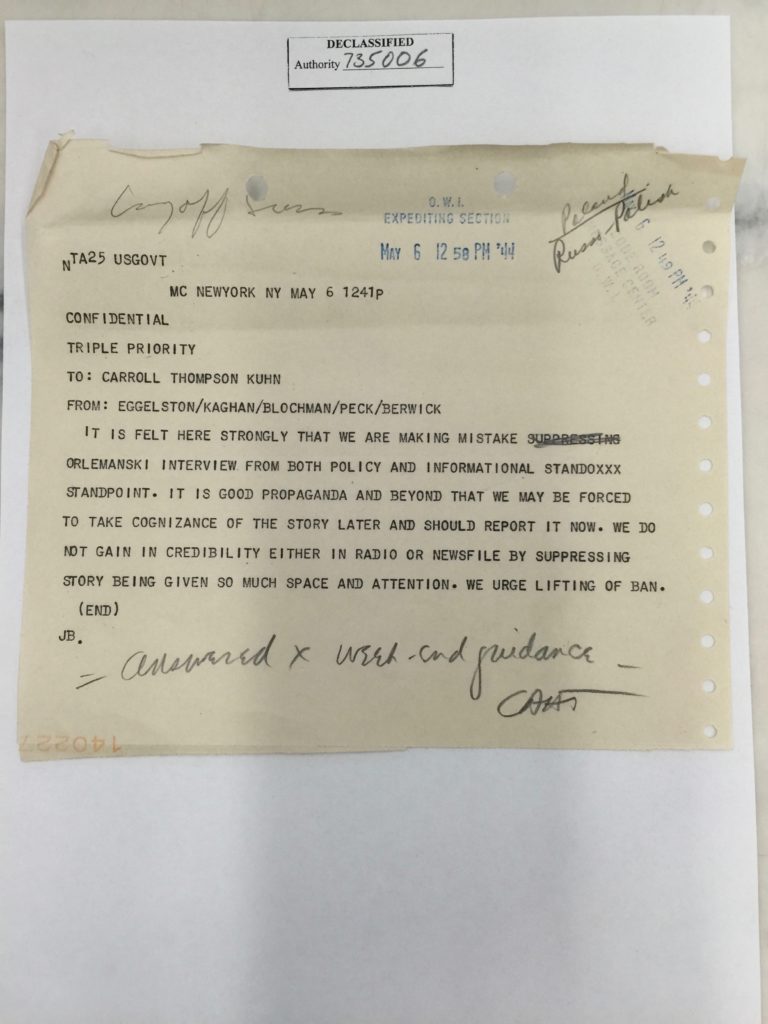

Even though President Roosevelt was privately satisfied with the results of the Lange-Orlemanski trip to Moscow, the State Department told the Office of War Information in late April 1944 to play down the story in Voice of America broadcasts. This upset pro-Soviet OWI officials and VOA journalists, who saw it as a great opportunity to highlight Stalin’s alleged goodwill toward Poland and to dispel the fear of Soviet communism. Even though a Washington Post opinion column called the Lange-Orlemanski’s trip “the phoniest propaganda that the usually clever-idea men in Russia have palmed off on the United States,” VOA journalists did not see it this way.

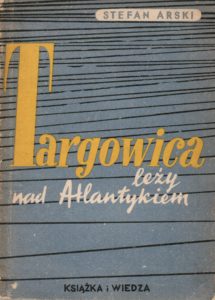

After the war, both Oskar Lange and Salman-Arski returned to Poland, joined the Communist Party, known as the Polish United Workers‘ Party, and for many years served the Moscow-dominated communist regime in Warsaw: Arski as an anti-American journalist writing anti-U.S. propaganda, and Lange as a diplomat and a high-ranking communist state official. Seweryn Bialer, himself an ex-Communist who after his defection to the West became later a respected scholar and professor of Soviet studies at Columbia University, helped to identify Salman-Arski in 1956 as an anti-American propaganda expert for the communist regime in Warsaw. Speaking through his interpreter, Georgetown University professor Jan Karski, Seweryn Bialer told a U.S. Senate subcommittee studying Soviet propaganda influence in the United States about Arski’s career in communist-ruled Poland.[ref]Jan Karski was a World War II anti-Nazi fighter who had briefed President Roosevelt on the Nazi Holocaust of Polish Jews. In 2012, President Barak Obama posthumously awarded Karski, who died in 2000 in Washington, D.C., with the country’s highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, for his World War II efforts to save Jews from the Nazi-German Holocaust. 1982, Israel’s Yad Vashem recognized Jan Karski as Righteous Among the Nations.[/ref]

Mr. Stefan Arski is presently in Poland. He is a journalist, and one of the most violently anti-western and anti-American journalists. He specializes in American affairs, and he contributes mostly to the People’s Tribune, an official organ of the Communist Party in Poland. He wrote several books which we used as a kind of basis for our anti-American propaganda.[ref]Scope of Soviet activity in the United States. Hearing before the Subcommittee to Investigate the Administration of the Internal Security Act and Other Internal Security Laws of the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, Eighty-fourth Congress, second session (Eighty-fifth Congress, first session), https://ia802205.us.archive.org/30/items/scopeofsovietact2730unit/scopeofsovietact2730unit.pdf. [/ref]

Oskar Lange

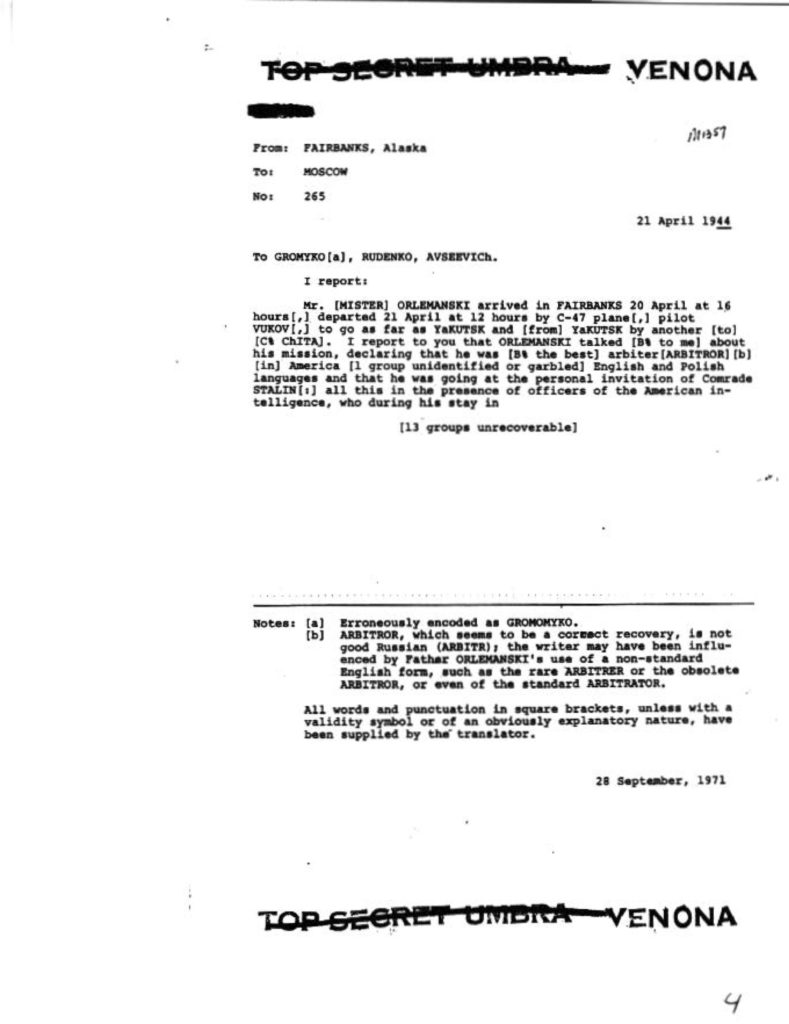

Born in pre-independent Poland in 1904, Oskar Lange emigrated to the United States and in 1938 became an assistant professor of economics at the University of Chicago, where he promoted the idea that nationalization of major industries and economic planning could be combined with market pricing tools in a socialist economy. He was naturalized as a U.S. citizen in 1943. After Lange was identified by the KGB as being sympathetic to the Soviet Union, Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin suggested to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s ambassador in Moscow Averell Harriman that Lange and two other Polish-Americans be allowed to travel to Russia to meet with him at the Kremlin. After President Roosevelt gave his approval, Lange met with Stalin in Moscow in May 1944 and later assisted in establishing the pro-Moscow communist regime in Poland and represented it in the United States as the first post-war ambassador and later as a delegate to the United Nations Security Council. Lange’s KGB connections in the United States are documented in Soviet intelligence messages decrypted by the U.S. Venona counterintelligence project. In post-war Poland, Lange was also a member of the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers’ Party (Communist Party) and deputy chairman of the Polish Council of State from 1961 to 1965 (a head of state function).

Artur Salman – Stefan Arski

Artur Salman, who in addition to Stefan Arski also used other pseudonyms and pen names: Jan Wiljan, Leliwa, Roman Warecki, S. Kalinowski, and Star, was born in 1910 in Łódź, in pre-independent Poland. Arski was initially an activist in the Polish Socialist Party, which in the interwar period of Poland’s independence participated in various coalition governments in Warsaw. Socialists were also represented in the wartime Polish government-in-exile in London. Salman-Arski came to the United States as a war refugee, traveling by ship from Japan to San Francisco.

In his job application for a position in the Office of War Information, dated July 16, 1943, Artur Salman listed Oskar Lange, Assistant Professor at the University of Chicago, as the first of his five references.

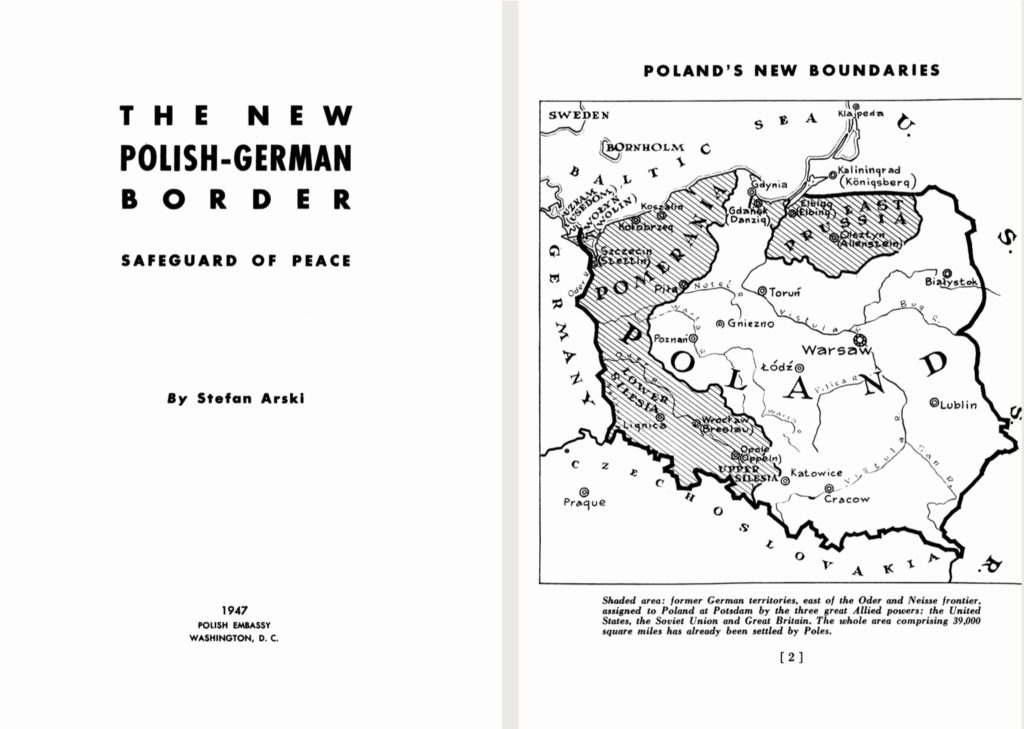

Salman-Arski did not list Lange as one of his references in his March 26, 1946 job re-application for a position in the U.S. State Department where the Voice of America broadcasting operations ended up after the war. President Truman abolished the OWI in his August, 31 1945 Executive Order 9608 which went into effect on September 15, 1945. At the time of Salman-Arski’s 1946 U.S. federal employment re-application for a position in the State Department, Oskar Lange, his former job reference on the 1943 OWI application, was already serving the communist regime as Poland’s ambassador in Washington. This time Salman-Arski probably did not want to attract State Department’s attention to his close links with Lange, but after he resigned from his VOA job in early 1947, the Polish Embassy in Washington published one of Arski’s books written in English in which he advocated for a final American recognition of Poland’s new Western border. The biographical note at the end of Arski’s book identified his former connection to the U.S. Office of War Information, where the Voice of America radio programs originated during World War II, but did not mention that he had worked on VOA broadcasts in the U.S. State Department until February 1947.

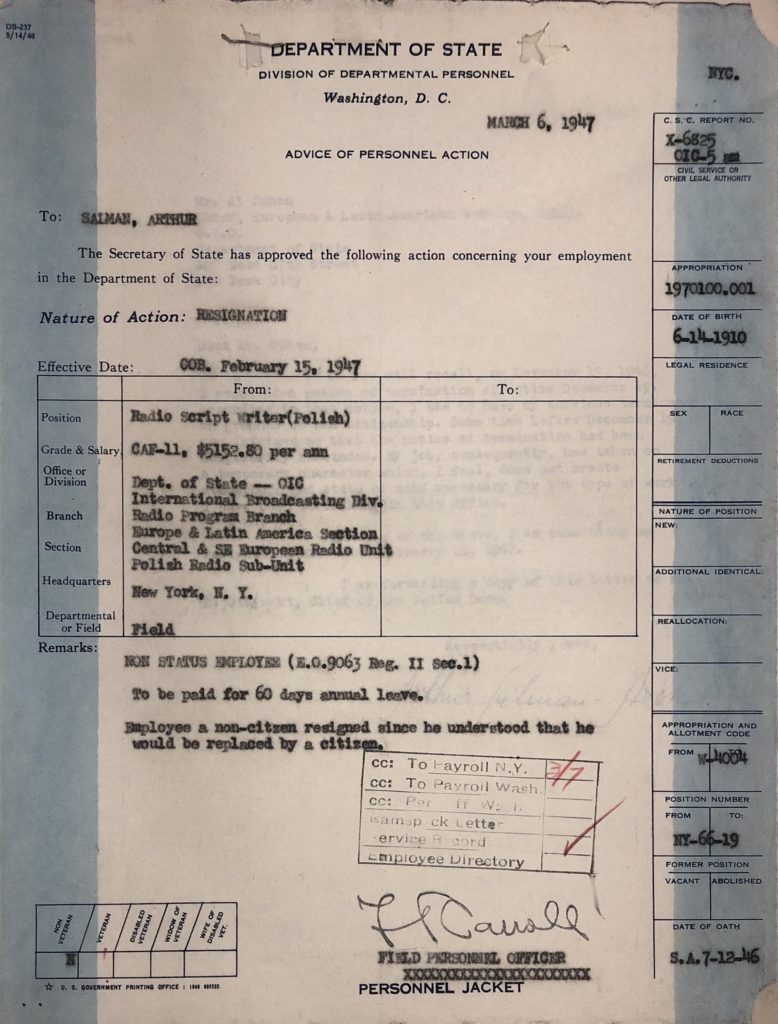

Salman-Arski was hired initially for the OWI’s division in charge of producing propaganda pamphlets, but in March 1946, he described his job duties as including “writing regular radio scripts, commentaries and news shows,” and being “/1945/ Head of the Polish Translation Unit.” His last U.S. government position was “Radio Script Writer (Polish)” in the State Department’s International Broadcasting Division, Polish Radio Sub-Unit. This was the Voice of America, although at that time it was still not widely known under its current official name.

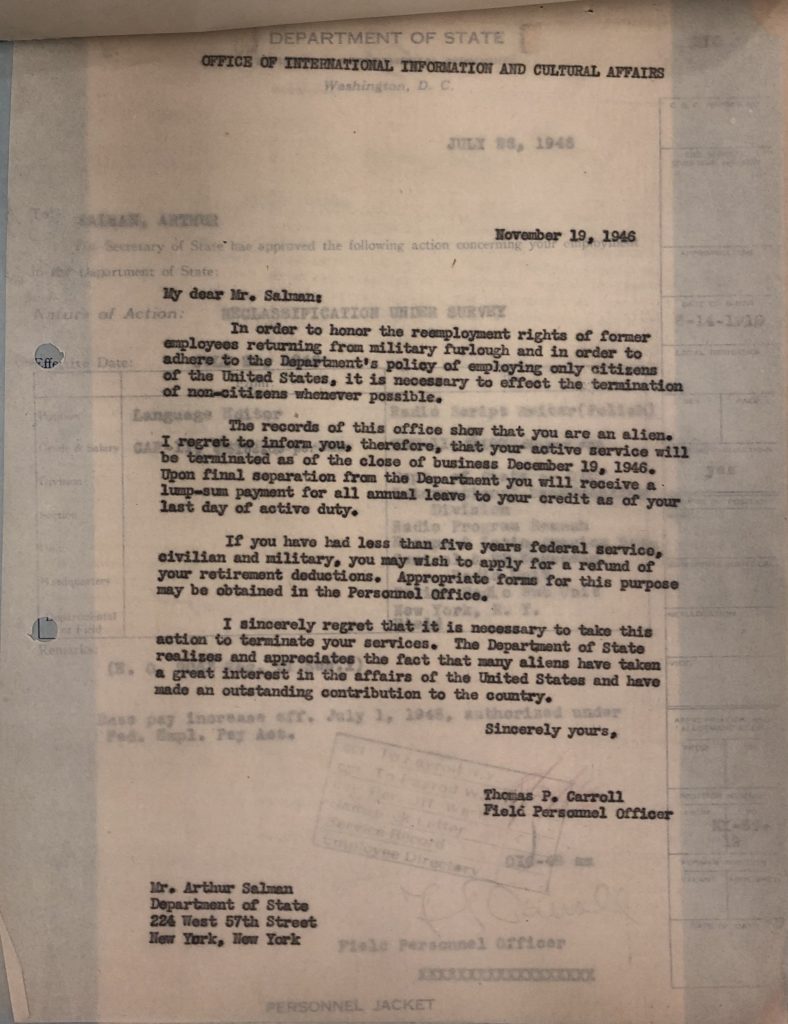

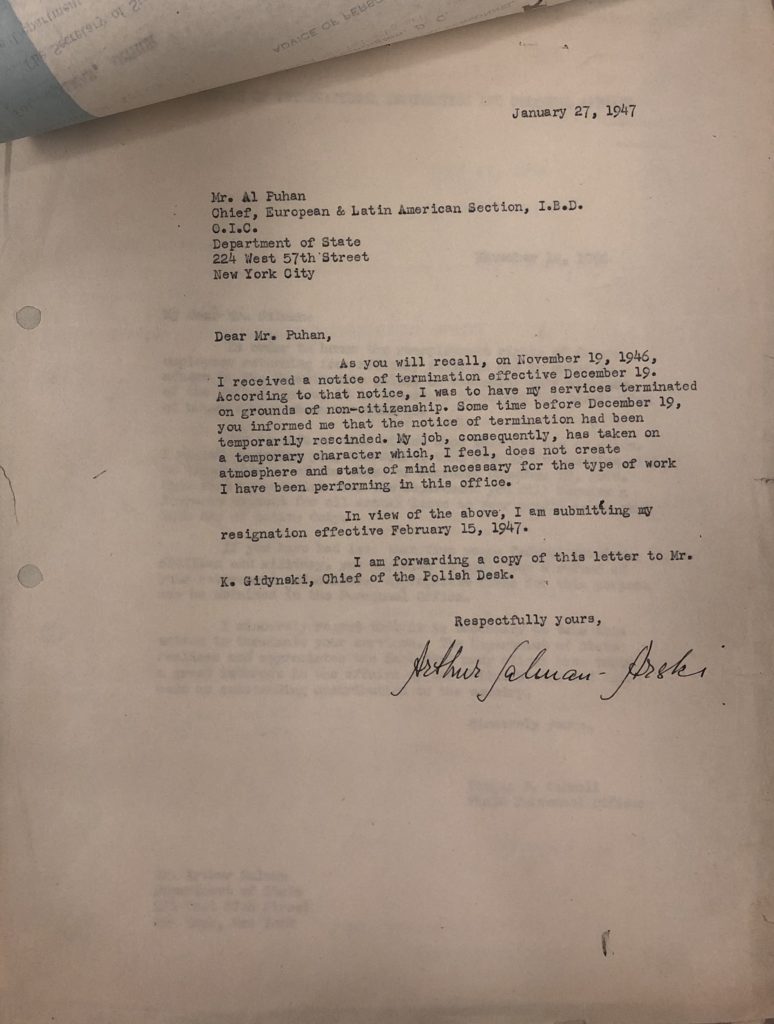

Salman-Arski might have stayed in his VOA job with the U.S. State Department, but he submitted his resignation effective February 15, 1947, after being informed that he would be replaced by a U.S. citizen. He signed his resignation letter, dated January 27, 1947, as Arthur Salman – Arski.

KGB Connection

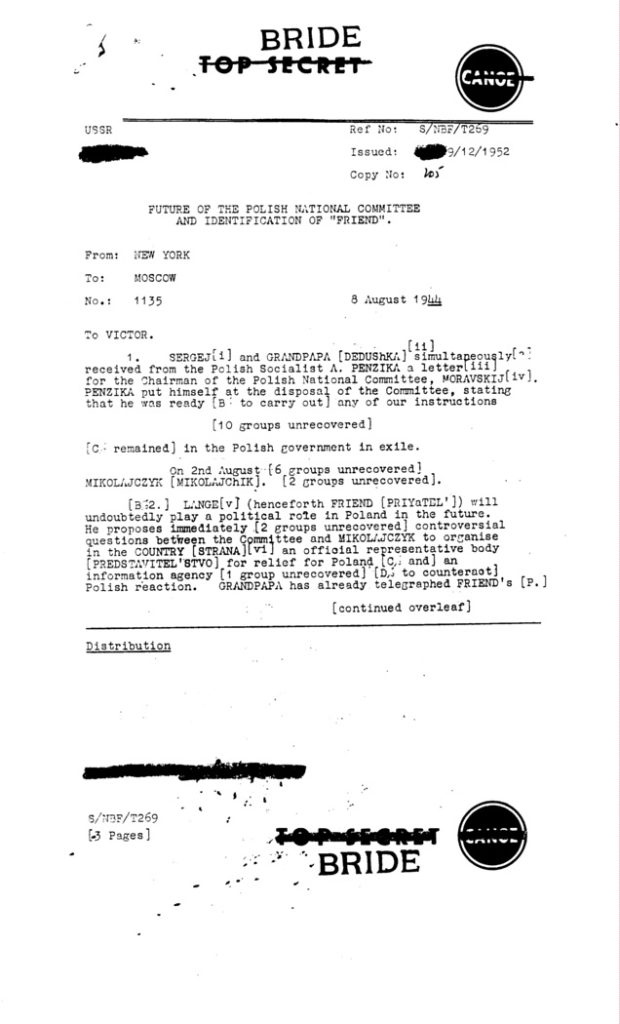

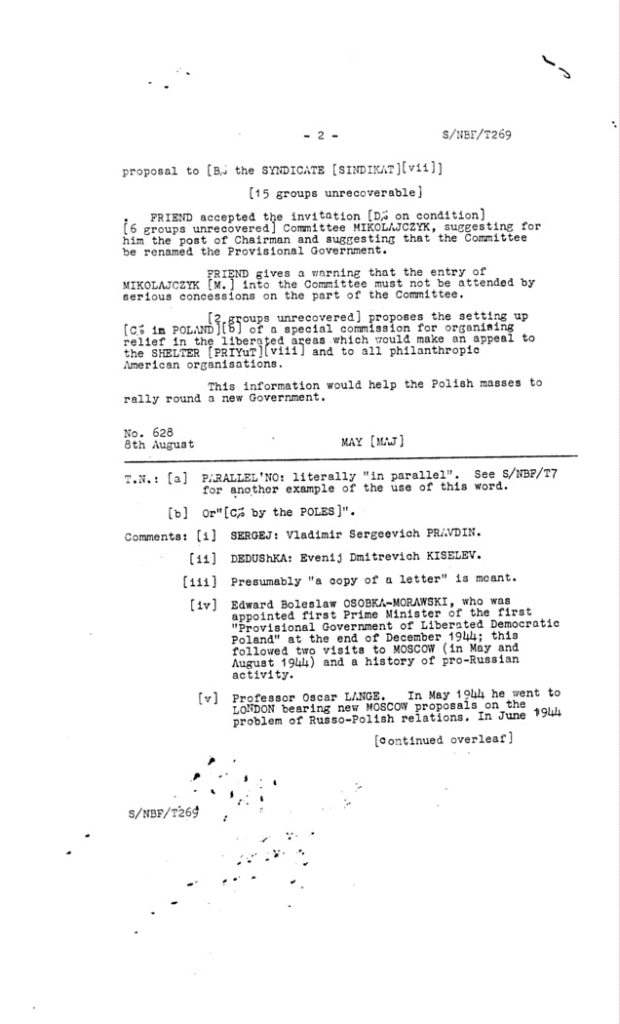

According to John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr, who conducted extensive research of the Venona project‘s Soviet secret intelligence cables, “Oscar Lange had reached a tacit agreement with the Soviets, via the KGB, even before he went to Moscow in 1944.” The two American historians noted that “the KGB also gave Lange a cover name–Friend–and told Moscow that he would ‘undoubtedly play a political role in Poland in the future’.” [ref]John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr, Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), 235.[/ref]In 1945, Oskar Lange did as predicted by Gebert. In 1945, Lange renounced his American citizenship, returned to Poland and became the communist regime’s first ambassador in Washington. Haynes and Klehr also mention Salman-Arski as a OWI employee and one of the “defenders of the Communist takeover of Poland,”[ref]John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr, Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), 197.[/ref] but do not link him directly in their book with Gebert or with Oskar Lange or his 1944 mission to Moscow.

The KGB officer working under diplomatic cover in the United States who managed Gebert, Lange and possibly also directly or indirectly Salman-Arski was Vasily Mikhailovich Zarubin whose cover name was Vasily Zubilin. While in the Soviet Union in 1939-1940, Zubilin was interrogating Polish military officers who were later murdered by the Soviets in the mass execution in the Katyn forest.[ref]John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr, Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), 45.[/ref]

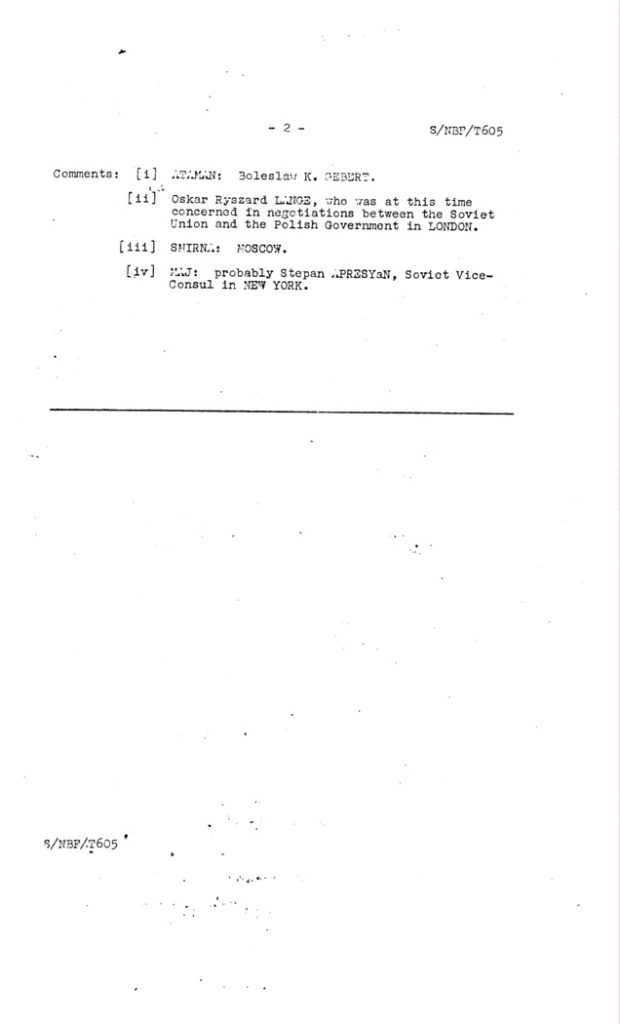

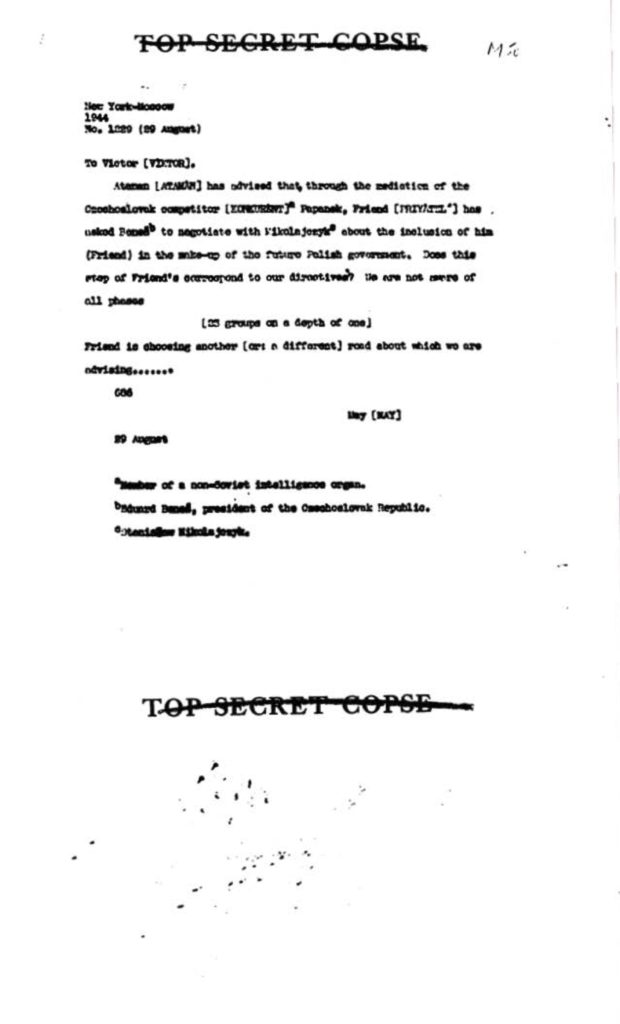

Haynes and Klehr showed that during World War II Lange was in touch with KGB agent Bolesław (Bill) Gerbert, a longtime Communist Party USA organizer who later also had a political career in communist-ruled Poland, including being the regime’s ambassador to Turkey. “ATAMAN” was Gebert’s KGB code-name. “SMYRNA” was the KGB code-name for Moscow. According to the analysis of the Venona cables by Haynes and Klehr, on the day Lange met with Stalin in Moscow, “the KGB in New York sent a cable with information that Bill Gebert felt was essential for Lange to have during his Moscow visit about internal émigré politics in the United States.”

Haynes and Klehr do not have information in their book on how Stanislaus Orlemanski, a well-meaning but extremely naive priest, was recruited for the mission, but his name appears in Venona cables. The KGB-organized propaganda publicity stunt was designed to convince President Roosevelt and American public opinion that Stalin supported freedom of religion in Poland and in the Soviet Union.

FDR Deceived By Soviet Propaganda

The U.S. State Department was not thrilled with the trip but went along with it apparently due to strong support from President Roosevelt. Later, however, the FDR White House became concerned after almost the entire Polish-American community, and therefore its voters, expressed firm opposition to the trip.

The KGB-conceived propaganda mission to Moscow also came under strong criticism from prominent American Catholics and parts of U.S. media not corrupted by Soviet influence operations. Rev. Msgr. Michael J. Ready, general secretary of the National Catholic Welfare Conference, wrote in the Washington Post that “the visit of an American priest of Polish descent to Russia is ‘a political burlesque, staged and directed by capable Soviet agents,’ for propaganda purposes.” “It is the ‘phoniest’ propaganda that the usually clever-idea men in Russia have palmed off on the United States,” Rev. Ready observed.

While distancing himself in public from Lange and Orlemanski and presenting their trip as a purely private initiative despite considerable logistical support for it from the U.S. government, President Roosevelt continued to promote to Stanisław Mikołajczyk, the Prime Minister of the Polish government-in-exile in London, what he thought were encouraging results of Lange’s and Orlemanski’s conversations with Stalin. According to Jan Ciechanowski, the ambassador to the United States of the Polish government-in-exile, during a White House meeting on June 12, 1944, President Roosevelt told Mikołajczyk that he had heard that Orlemanski was “pure and decent, possibly too naive, but with good intentions.”[ref]Jan Ciechanowski, Defeat in Victory (Garden City: Doubleday & Company, 1947), 308.[/ref]

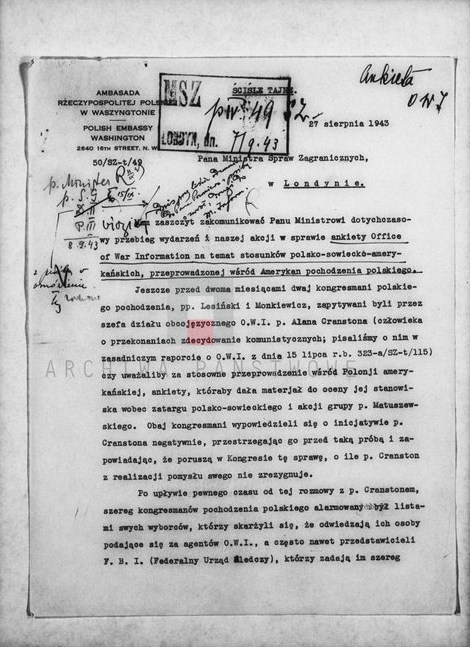

Ambassador Jan Ciechanowski made a significant contribution to protecting Americans from Soviet propaganda and disinformation being copied by U.S. government’s own pro-Kremlin propagandists and re-distributed in the United States. He worked hard behind the scenes in 1943 to convince many members of Congress of both parties to eliminate funding for most of the Office of War Information domestic propaganda activities which also extended to illegal censorship of American ethnic newspapers and radio stations.[ref]Cold War Radio Museum, “Polish Diplomat Who Exposed Pro-Stalin U.S. Propagandists,” December 16, 2018, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/the-polish-diplomat-who-fought-wwii-voice-of-america-pro-stalin-propaganda/.[/ref]

A secret cable sent by Ambassador Ciechanowski to the Polish government in exile in London, dated July 13, 1943, described the extent of Soviet propaganda influence in the Office of War Information and over its Voice of America radio broadcasts.

The situation worsened from the moment when the C.O.I. and O.F.F. offices were combined under the leadership of Elmer Davis, a journalist little familiar with European issues, crude, completely committed to the idea of using commercial advertising methods — in the American style — in political propaganda. Davis, aware of his ignorance, left political affairs in the hands of its assistants, such individuals as: Robert E. Sherwood, James Cowles, James P. Warburg, Joseph Barnes — all, without exception, pronounced sympathizers of Russia and communism, and — in the case of Cowles and Barnes — Willkie’s traveling companions on his trip to Russia and top promoters of the policy of “appeasement” toward Stalin.

Davis’ ignorance and advertising methods scared away from O.W.I. many of some of the most serious journalists who had been recruited before by Colonel Donovan and MacLeish, for example Henry F. Pringle, a well-known writer for the “Saturday Evening Post”; Ph. Hamburger, a commentator for the famous “New Yorker” and the author of our booklet “Tale of a City; Edgar A. Mowrer, I. Visson and fifteen others who had left the O.W.I. under some scandal. The chief of the O.W.I. press section, outstanding former editor of the “San Francisco Chronicle,” Paul Clifford Smith, our sincere friend, also resigned.

The O.W.I. started to attract mediocre journalists completely subservient to Davis’ politicized assistants mentioned above. Polish affairs were placed in the hands of a group of Polish citizens manifesting their pro-Soviet stand, such as T.N. Hudes, Al. Hertz, Art. Salman, M. Zlotowska and politically disoriented because of her long-term absence from Poland Mrs. Irena Balinska. She reports to Joseph Barnes, a declared communist, preparing flyers and propaganda publications designed for distribution in Poland.

As soon as this situation developed, I personally called Mr. Davis’ attention during a special visit to the inappropriate selection of Polish personnel. Despite his promises, my intervention produced no results. Similar interventions by Ambassadors from Greece, Holland and Yugoslavia– countries whose O.W.I. desks are staffed by communists and army and navy deserters, etc.–also met the same fate.

As our relations with Russia worsened, O.W.I. attitude toward us started to worsen more and more. For example, we were refused help in organizing this year’s 3rd of May radio program to be broadcast in the United States nationwide despite willingness by Congressional Majority and Minority leaders, McCormack and Martin, to record speeches. This, however, did not prevent us from moving forward with the program. Thanks to our personal contacts, the Columbia Broadcasting System gave us airtime needed on all stations on its network within two days. As the Minister knows from my report on the 3rd of May observances (No. 337a/SZ-114 from June 10, [19]43) the program was excellent. Similarly, our relations with the press were not damaged by O.W.I.’s hostile attitude. On the contrary — adjusting efforts by directly contacting the media while avoiding the O.W.I. produced better results than going through an intermediary. But in spite of this, the O.W.I. made our life difficult, especially during the period of the “Katyn Affair,” by withholding through censorship all of our major statements while letting the Soviet ones go through.

I have been exerting pressure on the O.W.I and will continue to exert it through several avenues. First of all, I inform the State Department about each confirmed O.W.I.’s biased report. However, the State Department is powerless. Secondly, I maintain very friendly relations with Mr. George Creel, currently the editor of the “Collier’s” weekly, the chief of American propaganda during the previous war and President Wilson’s close associate. Thanks to his position and his previous activity, Creel who is a very courageous man and, unlike Davis, very informed, in his direct talks with Davis points out mistakes and is not shy with sharp criticism. Additionally, Creel has access to leading members of the Senate, such senators as Bridges, Tydings, Byrd, and presents them with all of our complaints against the O.W.I. without revealing their source.

Thirdly, and finally — I am conducting my action through members of Congress who are of Polish descent. The Minister can be informed in detail by reading the attached “Congressional Record” (from June 17, 1943).

In the conversation with Mikołajczyk, Roosevelt mentioned news reports that Stalin had told Orlemanski that he had nothing against religious freedom, but would prefer to unify religions in the Soviet Union. Roosevelt interpreted this as an indication that Stalin would favor a union between the Russian Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches. Presented with such a ludicrous concept and Roosevelt’s suggestion that perhaps it would be useful to help Father Orlemanski to go to the Vatican to present this idea to Pope, Mikołajczyk responded diplomatically that “he would be ready to believe in the sincerity of Stalin’s declarations concerning freedom of religion only after Stalin freed the many Catholic priests whom he still held in Soviet prisons.”[ref]Jan Ciechanowski, Defeat in Victory (Garden City: Doubleday & Company, 1947), 309.[/ref]

President Roosevelt wanted to believe in Stalin’s promises. As Eleanor Roosevelt recalled in her 1949 memoir This I Remember, President Roosevelt believed that “the world was going to be considerably more socialistic after the war.”[ref]Eleanor Roosevelt, This I Remember (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1949), 253.[/ref] Eleanor Roosevelt also wrote with disarming honesty that her husband trusted Stalin when the Soviet leader had told him that the Russians will find themselves “growing nearer to some of your concepts and you may be finding yourselves accepting some of ours”[ref]Eleanor Roosevelt, This I Remember (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1949), 253.[/ref] and that he “had a real liking for Marshal Stalin.” In the same book, Eleanor Roosevelt noted that her late husband “enjoyed his first contact with Stalin” at the “Big Three” Teheran conference in late 1943 and thought that Stalin’s “control over the people of his country was unquestionably due to their trust in him and their confidence that he had their good at heart.”[ref]Eleanor Roosevelt, This I Remember (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1949), 316.[/ref] She also wrote that President Roosevelt “felt that by keeping our word we could build the confidence of this leader [Stalin] whose people, though fighting on our side, still did not trust us completely.”

Eleanor Roosevelt kept in touch with key officials in the Office of War Information, and her descriptions of Stalin were similar to how many OWI propagandists viewed the Soviet Union and its leader.

I have often thought that these three men, Stalin, Churchill and Roosevelt, in their very different ways, were extraordinarily good people to have been thrown together to achieve success in this war. All of them, without any question, led their people and gave so unstintingly of their own strength that they inspired confidence and respect.[ref]Eleanor Roosevelt, This I Remember (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1949), 316.[/ref]

Since Eleanor Roosevelt wrote this in her book published in 1949, it is obvious that neither she nor her husband viewed Stalin as the mass murderer and a completely untrustworthy adversary that he was.

After FDR’s conversation with Mikołajczyk at the White House, U.S. State Department diplomats later pressured the Polish prime minister to meet with Lange. Mikołajczyk, who regarded Lange as a “pro-Soviet propagandist,” reluctantly agreed to avoid any negative media publicity in the United States.[ref]Jan Ciechanowski, Defeat in Victory (Garden City: Doubleday & Company, 1947), 310.[/ref] In an ultimate show of desperate hope and good will, Mikołajczyk later agreed to join the communist-dominated government in Warsaw, but in 1947 he had to flee from Poland, fearing for his life after the communists with Soviet help started to arrest and execute members of his Peasant Party. Mikołajczyk understood the risks, but felt that he had no other choice. Pro-Soviet propagandists working for the Roosevelt administration showed, however, that they had full faith in Stalin and his promises of democracy and religious freedom in Poland. Mikołajczyk’s post-war (1948) assessment of Voice of America Polish wartime broadcasts as being the voice of Moscow is significant because, for a while, he was willing to cooperate with Stalin and the Communists in Poland.

We finally protested to the United States State Department about the tone of OWI broadcasts to Poland. Such broadcasts, which we carefully monitored in London, might well have emanated from Moscow itself. The Polish underground wanted to hear what was going on in the United States, to whom it turned responsive ears and hopeful eyes. It was not interested in hearing pro-Soviet propaganda from the United States, since that duplicated the broadcasts sent from Moscow.[ref]Stanislaw Mikolajczyk, The Rape of Poland: Pattern of Soviet Aggression (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1948).[/ref]

Soviet Influence Operation Exposed

Not everybody in the United States was fooled by Soviet propaganda. Members of the U.S. Congress of both parties had serious reservations about the Lange-Orlemanski mission to Moscow. One of the most frequent critics in Congress of the Office of War Information and its Voice of America broadcasts was Congressman John Lesinski Sr. (D-MI). He addressed the House of Representatives on May 2, 1944, telling the House that Professor Lange was “attempting to sell Communist Russia to Poland so that Poland would then become a republic— but within the boundaries of Russia,” and pointing out that “Reverend Orlemanski, a Catholic priest. American-born, of Polish parentage, has made this trip with Professor Lange without his bishop’s consent.“

The Polish Situation

REMARKS of

HON. JOHN LESINSKI

OF MICHIGAN

IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

Tuesday, May 2, 1944

Mr. LESINSKI. Mr. Speaker, according to press reports, Prof. Oscar Lange and Rev. Stanislaus Orlemanski have been received by Premier Stalin at Moscow as American representatives to discuss the Polish situation.

Oscar Lange was a professor in the Chicago University and became a citizen of the United States only about a year ago. He is a self-appointed, one-man representative of the Americans of Polish extraction, and is attempting to sell Communist Russia to Poland so that Poland would then become a republic— but within the boundaries of Russia. It seems that he is in favor of giving away a greater portion of present Poland as a gift. I say that only a rat or a Quisling would sell his own mother country to the hated Communist.

Reverend Orlemanski, a Catholic priest. American-born, of Polish parentage, has made this trip with Professor Lange without his bishop’s consent. Remembering Judas Iscariot who betrayed his Lord for 30 pieces of silver, I cannot help wondering what price this priest is asking to betray the land of his forefathers, his church, and the loyal Americans of Polish descent.

I am also wondering if the papal delegate and the bishop of his diocese will take the proper steps to unfrock this traitor to their church—a priest who has forgotten that it was through the valiant efforts of Poland, under the leadership of King John Sobieski, that Christianity was saved for Europe at Vienna In 1683.

I am wondering too why the State Department has issued visas which permitted the transportation of these two “representatives”—the traitors to Christianity, the land of their forefathers, and the principles of Americanism—to Russia at a time when Russia has renounced the principles as outlined in the Atlantic Charter.

It is definitely a matter to be given serious consideration. Yesterday, Rev. Msgr. Michael J. Ready, general secretary of the National Catholic Welfare Conference, issued the following statement, which appeared in the morning Washington Post:

Called “Burlesque”—Prelate Hits Soviet Visit of United States Priest

The visit of an American priest of Polish descent to Russia is “a political burlesque, staged and directed by capable Soviet agents,” for propaganda purposes, the Right Reverend Monsignor Michael J. Ready, general secretary of the National Catholic Welfare Conference, declared here yesterday.

“It is the ‘phoniest’ propaganda that the usually clever-idea men in Russia have palmed off on the United States,” he said.

The priest is the Reverend Stanislaus Orlemanski, of Springfield, Mass., who has been reported as having conferences In Moscow with Premier Stalin and other Soviet officials, concerning the fate of Poland alter the war. He left his parish, according to diocesan authorities, without obtaining the proper ecclesiastical permission.

MENTIONS STATE DEPARTMENT

Monsignor Ready, noting that the priest involved is known as a partisan of Soviet policy, recalled that other had heretofore tried unsuccessfully at the State Department to “get worthy priests to Russia.”

He referred to “stabbing In the back the Poland whose government this Nation recognizes.”

“Since Russia now considers the Polish forced exiles in her territory citizens of the U. S. S. R., will our Government, at the respectful request of millions of citizens, now issue a friendly endorsement for Russian passports for the priests and bishops imprisoned in Russia to come to the United States to enjoy the four freedoms?” he asked.

Monsignor Ready spoke at a communion breakfast of the regional supervisors of the National Catholic Community Service at the National Catholic School of Social Service here. Senator John A. Danaher of Connecticut, also spoke…

In a speech in the House of Representatives on May 4, 1944, Congressman Lesinski continued to pose questions about the Roosevelt administration’s support for the Lange-Orlemanski trip to Moscow and suggested that both Lange and Orlemanski should have registered as foreign agents.

Polish Constitution Day

REMARKS OF

HON. JOHN LESINSKI

OF MICHIGAN

IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

Thursday, May 4, 1944

Mr. LESINSKI. Mr. Speaker. I take this opportunity to thank the Speaker of the House, the majority and minority floor leaders, and all of the Members of the House of Representatives who participated in the celebration of the one hundred and fifty-third anniversary of the adoption of the Polish Constitution yesterday, May 3, 1944. May the Stars and Stripes and the White Eagle of Poland be united in victory.

I was particularly impressed last night while listening to the radio program. Report to the Nation, by the remarks of Quentin Reynolds when he stated that although Poland had lost over 5,000,000 people in this desperate struggle, she had not produced a Quisling, and that the Polish people had remained steadfast and faithful to the cause of the United Nations and would rather die than to be tray their faith in that cause.

Another commentator in his report of the national news brought out the mat ter of Reverend Orlemanski’s trip to Moscow—he said that friends of the father in New York stated that both the high officials in Washington and the high officials of the church knew about that trip. Now, just who could his friends in New York be? Well, this morning I received a postal card from New York which warned me “to leave Reverend Orleman- ski alone as he is trying to pull Poland out of the seventeenth century.” It was signed, “A Brooklyn Catholic.” There is some doubt in my mind as to whether the writer of this card has ever been in side a Catholic church. He is nothing but a Communist, and, therefore, communistic tactics are the only ones he knows. Having 52 nationalistic groups in my congressional district, I know the underhanded methods of the Communist. They even go to the extent of joining the churches, the civic organizations, and the patriotic societies—they then start their boring from within. They even attend church services although they do not believe in it—but only so that they may perform their dirty task of undermining. A lie does not mean anything to a Com munist or the misrepresentation of a true fact just so long as he is able to gain his point and attain his ultimate goal. It matters not to a Communist how long it will take him or by what means he will have to travel to reach his goal or the expense he may incur—the result is what counts with him.

I repeat what I have said before—it is time for those in authority in the United States to quit quibbling about diplomacy and worrying whether or not we might embarrass one of our allies, and stand four-square behind their oath of office to uphold the Constitution and the American form of government, and get to the bottom of these communistic agitations and the other efforts of the Communists to indoctrinate Americans with their ideologies.

You hear so many stories in regard to Reverend Orlemanski’s trip to Europe— well, here is one that is based on fact: When New York newspapermen went to Springfield, Mass., to ascertain from the chief of police there the basis of the clearance for the visa that was issued to Reverend Orlemanski, they were in formed by the chief of police that he did not know very much about how Reverend Orlemanski got his visa—he was simply instructed by the State Department to fingerprint him, and during the process of that fingerprinting, Reverend Orlemanski remarked that a copy of his fingerprints had better be kept because he might not ever return from Russia. It would be interesting to know by what means Reverend Orlemanski really reached the Kremlin or how long he has been planning this trip and just what information he has been collecting here in America. Reverend Orlemanski is even being protected by our State Department—our own State Department has failed to explain to the American people the reasons behind his visit to Russia. They have on the statute books a provision that requires foreign agents to register—many people are wondering whether Reverend Orlemanski and Professor Lange, well-known Russian sympathizers, are really foreign agents of Russia, and if they are the agents of Stalin, and there appears that there is some connection for he journeyed to the Kremlin to report to his master—why have the names of Reverend Orlemanski and Professor Lange not appeared on the published list of registered foreign agents residing in America?

Well, if it is so easy for a Catholic priest indoctrinated with communistic ideologies to get to Russia, I believe we should make it as easy for the rest of the communistic sympathizers and agita tors residing in the United States to go there. Let us just load them all on a boat and send them back; in fact, I am so eager to see them leave that I am in favor of furnishing them transportation by air. Stalin, no doubt, can use them to good advantage. Certainly, the people of America, with true American ideals, have no use for them.

On May 11, 1944, Congressman Lesinski informed the House of Representatives that he had written letters about the trip to Moscow by Rev. Orlemanski and Professor Lange to Secretary of State Cordell Hull and Attorney General Francis Biddle. After Secretary Hull responded that Orlemanski and Lange were traveling to Moscow as private American citizens, acting in their own individual capacities, Congressman Lesinski suggested that they had violated U.S. law by not registering as foreign agents and by “carrying on both verbal intercourse and written correspondence with a foreign government with the intent to influence the measures and conduct of that government in relation to the policies of the United States.”

In his letter to Attorney General Biddle, Congressman Lesinski wrote that “both Reverend Orlemanski and Professor Lange are well known in this country as Soviet sympathizers.”

Rev. Stanislaus Orlemanski and Prof. Oscar Lange

EXTENSION OF REMARKS

OF

HON. JOHN LESINSKIOF MICHIGAN

IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

Thursday, May 11, 1944

Mr. LESINSKI. Mr. Speaker, under leave to extend my remarks in the Record, I include a letter I have forwarded today to the Attorney General, Hon. Francis Biddle, relative to Reverend Orlemanski and Professor Lange:

House of Representatives,

Washington, D. C., May 8, 1944.

Hon. Francis Biddle,

The Attorney General,

Department of Justice,

Washington, D. C.

DEAR GENERAL BIDDLE: I am writing you in regard to the case of the Reverend Stanislaus Orlemanski and Prof. Oscar Lange, to whom there has been considerable reference in the press recently, as well as over the radio, in regard to their trip to the Soviet Union. Under date of May 1, 1944, I addressed a letter to the Honorable Secretary of State and inquired as to the information the State Department had relative to this trip.

Under date of May 6, 1944, I received the following reply from Secretary Hull:

“The receipt is acknowledged of your letter of May 1, 1944, relative to the visit of the Reverend Stanislaus Orlemanski and Prof. Oscar Lange to the Soviet Union.

“In reply I wish to inform you that Father Orlemanski and Professor Lange proceeded to the Soviet Union on the invitation of the Soviet Government, which furnished their transportation to Moscow. They are making this trip as private American citizens, acting in their own individual capacities. They have no official status, and therefore are not in any sense representatives or spokesmen of the United States Government.

“On the basis of the fact that they were officially invited by a friendly Allied power to make this trip, passports were issued to them, valid for their journey to Moscow.”

It is quite apparent from the foregoing letter of the Secretary of State that Reverend Orlemanski and Professor Lange were acting in their own individual capacities, as specially invited guests of the Soviet Union. I am, therefore, of the opinion that both Reverend Orlemanski and Professor Lange have directly violated the provisions of section 5 of the Penal Code of the United States. Both Reverend Orlemanski and Professor Lange are well known in this country as Soviet sympathizers, and the entire purpose of their visit to the Soviet Union was to disrupt the unity of the United Nations. This country is committed to a policy of nonrecognition of territorial acquisition by force, and from the press releases and radio reports it is evident that they are endeavoring as individuals to convert the 6,000,000 Americans of Polish descent to the Soviet’s program in regard to Poland.

Reverend Orlemanski has been active for the Soviet cause and assisted in organizing the Kosciusko League in Detroit last fall, which is a Communist-controlled organization.

In the case of Professor Lange, he has been a naturalized citizen of the United States for a period of a little more than a year, and it is quite evident by his actions that his sole purpose of becoming i citizen of this country was to give him the protection afforded to Americans, and at the same time use that cloak of Americanism to protect him while spreading the doctrines of the Soviet Union. He certainly cannot, by any stretch of the imagination, be accepted as a true American—one who believes in the American way of life and a democratic form of government. I am of the opinion that proper legal steps should be taken by the Department of Justice to take away from him his American citizenship.

Inasmuch as Reverend Orlemanski and Professor Lange have violated the provisions of our Penal Code, I am calling on you to take appropriate action, upon their return to this country, as it is quite apparent that they have been carrying on both verbal intercourse and written correspondence with a foreign government with the intent to influence the measures and conduct of that government in relation to the policies of the United States. I am also calling upon you to take appropriate action as to these individuals in regard to their acting as agents for a foreign country without being properly registered by our State Department in accordance with existing law.

With best wishes and kindest personal regards and an expression of my highest esteem, I am,

Very sincerely yours,

JOHN LESINSKI,

Member of Congress.

PENAL CODE

Sec. 6. Every citizen of the United States, whether actually resident or abiding within the same, or in any place subject to the jurisdiction thereof, or in any foreign country, who, without the permission or authority of the Government, directly or indirectly, commences or carries on any verbal or written correspondence or intercourse with any foreign government or any officer or agent thereof, with an intent to influence the measures or conduct of any foreign government or of any officer or agent thereof, in relation to any disputes or controversies with the United States, or to defeat the measures of the Government of the United States; and every person, being a citizen of or resident within the United States or in any place subject to the jurisdiction thereof, and not duly authorized, who counsels, advises, or assists in any such correspondence with such intent, shall be fined not more than $5,000 and imprisoned not more than 3 years; but nothing in this section shall be construed to abridge the right of a citizen to apply, himself or his agent, to any foreign government or the agents thereof for redress of any injury which he may have sustained from such government or any of its agents or subjects. (Revised Statutes, sec. 5335; Mar. 4. 1909, ch. 321, sec. 5, 35 Stat. 1088; Apr. 22. 1932. ch. 126, 47 Stat. 132.)

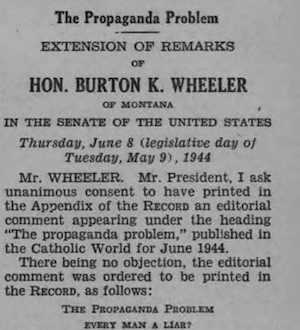

On June 8 (legislative day of May 9), 1944, U.S. Senator Burton K. Wheeler (D-MT) inserted in the Congressional Record an editorial titled “The propaganda problem,” which was published in the June edition of Catholic World and included a comment on Father Orlemanski’s trip to Moscow.

The Catholic World commentary was critical of a strongly left-leaning American journalist, William L. Shriner, for his uncritical acceptance of Soviet propaganda.

Let us have a few examples to illustrate the difficulty of determining what is propaganda and what is not. Rev. Stanislaus Orlemanski, of Springfield, Mass., goes A. W. O. L. from his diocese to—of all places—Moscow, to have a chat with—of all people—Stalin. He comes back with the information that Stalin is friendly to Roman Catholics. Monsignor Ready, general secretary of the National Catholic Welfare Conference, declares the incident to be “political burlesque” and “phoniest propaganda.” What say, Mr. Shirer? Is it propaganda? Yes? No? How do you know? In a spirited comeback. Father Orlemanski rebukes Monsignor Ready for using “such vulgar words” and for “trying to undermine his priestly and Christly life by innuendos.” Skipping the question as to how a vulgar word can be an innuendo, will Mr. Shirer give us some rule of thumb by which we may determine which of the two clergymen is the propagandist? As far as we ourselves are concerned, we feel that we know, but is there some infallible standard of determination? Something that would convince others as we are convinced? Father Orlemanskl reports Stalin as calling himself “an advocate of freedom of conscience and of worship.” Was the wily Georgian merely ribbing Father Orlemanskl or was he handing out propaganda which he expected Americans to swallow? And will they swallow it? They will unless we can prove It to be propaganda. How would you go about it, Mr. Shirer? Or would you go about it?

Other Congressional Warnings

One of the earliest warnings of Soviet subversion of U.S. government overseas radio broadcasts came in April 1943 from Republican U.S. Senator from Ohio, Robert A. Taft, the son of William Howard Taft, the 27th President of the United States. In a speech on the Senate floor on April 19, 1943, Senator Taft warned of “ugly rumors abroad” that much of American “short-wave broadcasting is futile and idiotic, and very inferior to that of other nations.” “It is said that some of it is communistic and some of it is fascistic, and that much of it tries to play European politics, about which we know nothing, instead of presenting the American point of view,” Senator Taft added. There was no evidence that any of VOA programming during the war was intentionally pro-Nazi—it was intended to be strongly anti-Nazi—although some of the simplistic anti-Nazi propaganda could have been seen as having an impact contrary to its intended aims.

There was, however, clear evidence of massive VOA propaganda in favor of the Soviet Union and Stalin’s plans to control Eastern Europe to the point of harming American interests and damaging America’s other allies and their democratic governments against whom some of the Soviet-inspired VOA propaganda was directed.

At the time Salman-Arski was employed by the Office of War Information, Congressman Roy O. Woodruff (R-MA) delivered on April 20, 1943 on the floor of the House of Representatives another early warning of Soviet influence over America’s radio outreach abroad. In addition to VOA broadcasts to Poland, Congressman Woodruff also focused on VOA broadcasts to Yugoslavia, charging that both might have fallen under communist influence.

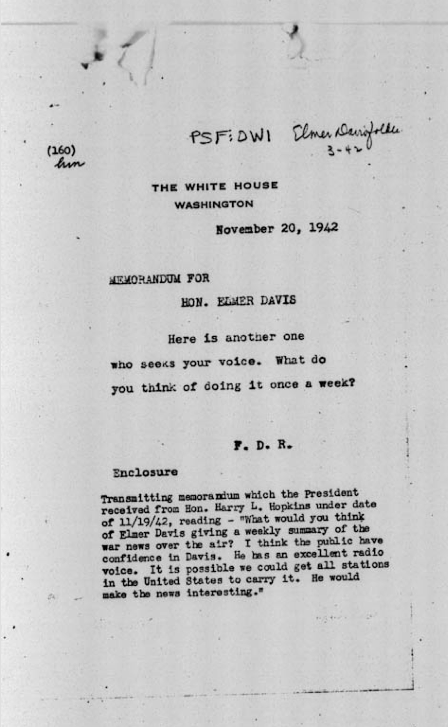

Soviet Katyn Lie

In April and May 1943, the Office of War Information Director Elmer Davis, who was appointed to this position in the newly created agency by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in June 1942, began spreading the Soviet propaganda lie about the Katyn forest massacre of thousands of Polish military officers. He did it in broadcasts on domestic U.S. radio networks, as well as in Voice of America radio transmissions overseas. VOA programs were produced in New York by the U.S. government wartime propaganda agency under his overall direction. At an earlier request from President Roosevelt, Davis recorded weekly commentaries, which were broadcast during part of the war domestically on U.S. radio networks. Thus, the Executive Branch had a propaganda outlet to address both American radio listeners and radio listeners abroad.

Soviet propaganda messages, including the Katyn lie, were spread by the Roosevelt administration to both domestic and foreign audiences despite protests in the U.S. Congress and critical reports by some of the private media. Elmer Davis remained in charge of the Office of War Information until September 1945 when it was dissolved by President Truman. He claimed after the war that he was convinced at the time of his Katyn radio broadcast that the Germans had committed the mass murder of Polish officers. He could rely on the first director of the Voice of America, John Houseman, and his broadcasters in getting the Soviet message about Katyn to the international audience. Houseman was secretly identified by the State Department and the U.S. Army Intelligence in early April 1943 as a Soviet sympathizer who was hiring communists to fill VOA broadcasting positions. Even if the vast majority of them were not actual Soviet agents of influence, they determined the tone and content of VOA broadcasts, and most of them, unless they were clearly identified as Communist party members, enjoyed the full support of their agency’s leadership.

In mid-April 1943, shortly after the Germans announced the discovery of the Katyn graves and Soviet Russia denied any responsibility for the mass murder, the U.S. State Department advised Elmer Davis to avoid taking sides on the Katyn massacre, but he ignored the advice of U.S. diplomats and others who told him that the atrocity was almost certainly committed by the Soviets. At that time, the VOA Polish desk in New York was dominated by communist sympathizers working with John Houseman, who promoted the Soviet Katyn lie as a true news story.

Robert Sherwood advised VOA broadcasters in his “Weekly Propaganda Directive” dated May 1, 1943 that “some Poles” who did not accept the Soviet explanation, may be cooperating with Hitler in causing division among the allies, even though Poland was a Nazi-occupied country where such cooperation with Nazi Germany on the part of the underground state, its underground army or the government in exile in London was beyond unthinkable.

Some Poles are consciously or unconsciously cooperating with Hitler in his campaign to spiritually divide the United Nations.[ref]Robert E. Sherwood, Director, Overseas Branch, Office of War Information; RG208, Director of Oversees Operations, Record Set of Policy Directives for Overseas Programs-1942-1945 (Entry363); Regional Directives, January 1943-October 1943; Box820; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.[/ref]

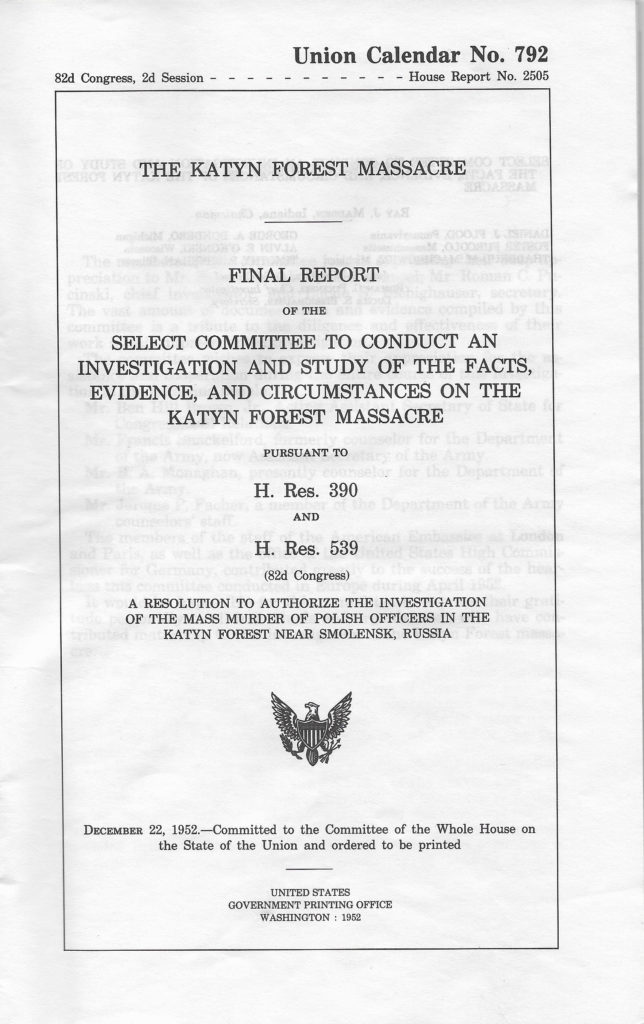

After the war, the bipartisan Select Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives to Conduct an Investigation and Study of the Facts, Evidence and Circumstances of the Katyn Forest Massacre, also known as the Madden Committee, said in its “Final Report” issued in December 1952 that the Office of War Information misled Americans and foreign audiences about the true nature of the Soviet regime and that some disinformation continued even for a few years after the war.

In submitting this final report to the House of Representatives, this committee has come to the conclusion that in those fateful days nearing the end of the Second World War there unfortunately existed in high governmental and military circles a strange psychosis that military necessity required the sacrifice of loyal allies and our own principles in order to keep Soviet Russia from making a separate peace with the Nazis.

The committee added:

For reasons less clear to this committee, this psychosis continued even after the conclusion of the war. Most of the witnesses testified that had they known then what they now know about Soviet Russia, they probably would not have pursued the course they did. It is undoubtedly true that hindsight is much easier to follow than foresight, but it is equally true that much of the material which this committee unearthed was or could have been available to those responsible for our foreign policy as early as 1942.

The Madden Committee also said in its “Final Report” in 1952: “This committee believes that if the Voice of America is to justify its existence, it must utilize material made available more forcefully and effectively.”

Under strong pressure from Congress, a major change in VOA programs occurred in the early 1950s, with much more reporting being done on the investigation into the Katyn massacre and other Soviet atrocities, but later some cover-up of the Katyn story resumed. Radio Free Europe (RFE), also funded and indirectly managed by the U.S., never resorted to such censorship, providing full coverage of all communist human rights abuses.

The bipartisan Madden Committee concluded in 1952 that while some measures taken by the Office of War Information could have been excused as a wartime necessity with regard to Russia as a military ally, American officials and VOA journalists misled the American public and foreign audiences about the true nature of the Soviet regime thus preventing a more pragmatic policy toward Russia from being adopted. Considering the cost of the failure of the Yalta Agreement, it was a profoundly serious charge that was never answered and was quickly forgotten. Warnings and recommendations issued in 1952 by the bipartisan Madden Committee, named after its chairman Ray Madden (D-IN), resulted, however, in eliminating some of the Voice of America censorship of news and information about Soviet human rights abuses and genocidal crimes, including the Katyn massacre.

On November 11, 1952, the Madden Committee grilled Elmer Davis over his Soviet Katyn propaganda lie broadcasts. He was asked to read a large portion of his May 3, 1943 Voice of America commentary from a transcript reported at the time by the U.S. Embassy in Sweden. [ref]The transcript read by Elmer Davis during his 1952 congressional testimony and presented by the Select Committee on the Katyn Investigation as one of the exhibits differs slightly from the original audio recording, but does not alter its meaning. Minor edits might have been introduced in transcription.[/ref]

In response to questions from committee members, Davis gave a number of both revealing and misleading answers. After he was asked whether he knew some of the communist sympathizers employed by the Office of War Information, including Salman-Arski, Davis lashed out at Congressman John Lesinski Sr. and other critics of his former agency.

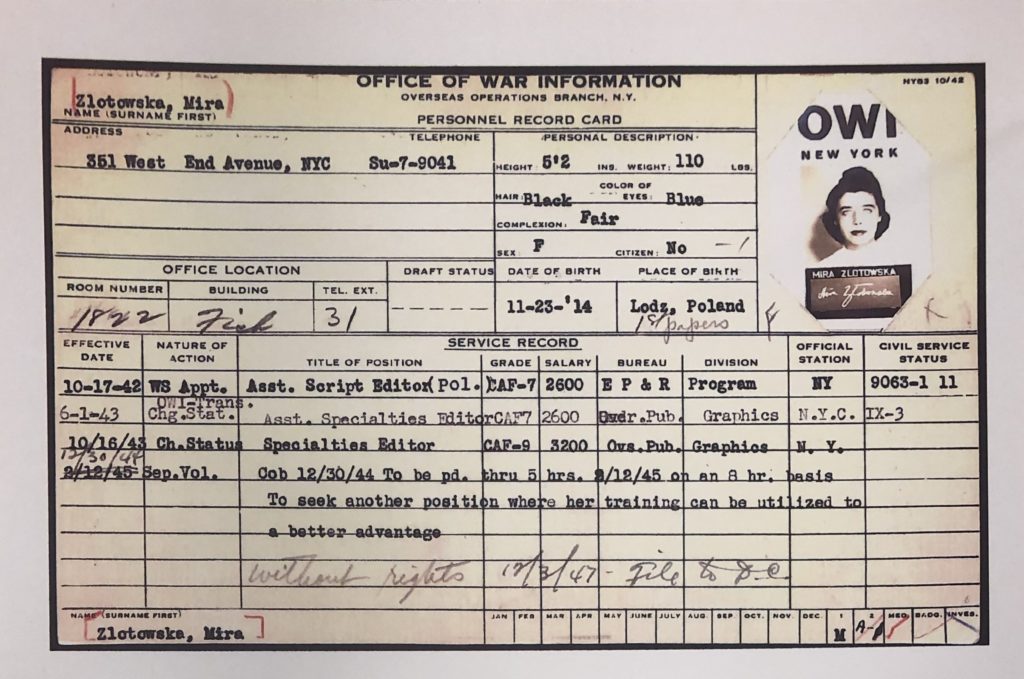

In his testimony before the bipartisan committee, Davis told Congressman Thaddeus M. Machrowicz (D-MI), a Polish immigrant who as a young child came to the United States in 1902, that he did not recall knowing Stefan Arski. He also said that he had never known or heard of Mira Złotowska, Arski’s colleague at the Office of War Information, who also worked on writing and editing Voice of America broadcasts. There were rumors that Arski and Złotowska were linked romantically.

Chairman MADDEN. Mr. Machrowicz.

Mr. MACHROWICZ. Mr. Davis, how long did you remain with the Office of War Information? When did you sever your relationship with the Office of War Information?

Mr. DAVIS. September 15, 1945.

Mr. MACHROWICZ. During the time that you were in the Office of War Information, had you ever known of the reports of Colonel Van Vliet and Colonel Stewart?

Mr. DAVIS. Never, sir. As far as I can recall now, I never heard of those reports until they came out in the investigations of this committee.

Mr. MACHROWICZ. Those reports, which indicated Russian guilt, were never made known to you?

Mr. DAVIS. No, sir.

Mr. MACHROWICZ. Now, how large a staff did you have in the Office of War Information?

Mr. DAVIS. Well, at the peak we had about 9,000 here and abroad. 5,000 Americans, and about 4,000 of what we called locals, chauffeurs and interpreters, and things like that.

Mr. MACHROWICZ. Did you have a so-called Polish Section?

Mr. DAVIS. Yes. sir.

Mr. DAVIS. A good many of them were there when I came. They had come from the predecessor organization, the Coordinator of Information. I don’t remember who selected the man who was the head of our Polish desk in Washington, Mr. Ludwig Krzyzanowski, but he was a very sound man.

Mr. MACHROWICZ. How were these people selected?

Mr. MACHROWICZ. Did you know the late Congressman John Lesinski?

Mr. DAVIS. I have had some correspondence with Mr. Lesinski.

Mr. MACHROWICZ. Was it at the time you were in the Office of War Information?

Mr. DAVIS. No; just recently—I mean 2 or 3 years ago.

Mr. MACHROWICZ. Do you have a recollection that Congressman John Lesinski, the late Congressman—I mean the senior Mr. Lesinski—having warned you about the fact that there were several Communists in the Office of War Information?

Mr. DAVIS. I don’t recall that. I recall that he made a speech in the summer of 1943 which contained more lies than were ever comprised in any other speech made about the Office of War Information,

and that is saying quite a lot. I may say that I have made that statement to Mr. Lesinski before he died. I mean that I have not waited until after he is dead. I told him so in writing when he repeated some of those statements 2 or 3 years ago. I asked him where he got the information, because that was a perfectly absurd speech to be made by a Member of the Congress of the United States who knows anything about American politics or the American news business.

Mr. MACHROWICZ. Now, let me ask you whether you received any warnings from the then Polish Ambassador to the United States, Ambassador Ciechanowski, warning you about the fact that there were some Communist employees in the OWI?

Mr. DAVIS. I received a great number of allegations from Mr. Ciechanowski. I can’t remember all of them now, but they were investigated, and, as I recall, there was no convincing evidence to support them.

Mr. MACHROWICZ. Do you know Irene Belinska [correct spelling: Balinska], who was in the Polish Section?

Mr. DAVIS. I don’t remember here.

Mr. MACHROWICZ. For your information, she was at that time one of the members of the Polish Section in your office.

Mr. DAVIS. Was she here or in New York?

Mr. MACHROWICZ. In Washington. She is the daughter of Ludwig Rajchman, who was the first consul of the Polish Communist Embassy in Washington in 1945. Rajchman engineered the surrender of the Polish Government in exile’s files to the Polish Communist Government in Washington. In 1947, this same Miss Balinska returned to Poland—she was then employed by the Office of War Information—returned to Communist Poland and then came back to the United States and is now with a Polish Communist publishing house which publishes an anti-American newspaper. Did you know that?

Mr. DAVIS. She could not have been employed by the Office of War Information in 1947, because we had folded up.

Mr. MACHROWICZ. No, not in 1947. It was prior to that time.

Mr. DAVIS. I don’t remember.

Mr. MACHROWICZ. You don’t remember having been warned by Ambassador Ciechanowski or by anyone else about the fact that she was in your employ and that she was a Communist?

Mr. DAVIS. I don’t remember. It may have happened. I don’t know; it is a long time ago.

Mr. MACHROWICZ. Did you know a Mira Zlotowski, who was in your employ in 1945?

Mr. DAVIS. I don’t recall. Mr. Krzyzanowski was the only man I ever had much dealing with, as I say, as the head of our Polish desk in Washington.

Mr. MACHROWICZ. Did you know Mrs. Zlotowski, the wife of Prof. Ignatius Zlotowski. the counselor of the Polish Communist Embassy in Washington, who was denounced as a Communist by General Modelski of the Polish Embassy, who had resigned? He testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee that Mrs. Zlotowski was a Communist agent.

Mr. DAVIS. I have no doubt of that.

Mr. MACHROWICZ. You don’t remember her being employed by the Office of War Information?

Mr. DAVIS. She may well have been. I don’t remember. As I say, the only man I dealt with was Mr. Krzyzanowski, who after he left us, went to the United Nations. For 3 or 4 years the Polish Communist Government tried to get him out of his job at the United Nations because he was working for us. I don’t know whether he is still employed there.

Mr. MACHROWICZ. Did you know a Stefan Arski, alias Arthur Salman?

Mr. DAVIS. No.

Mr. MACHROWICZ. For your information, he was also employed by the Office of War Information in 1945. He is now in Warsaw, Poland, and is editor in chief of the Communist paper Robotnik, which means The Worker, the most outspoken anti-American organ in Warsaw. He at that time was also an employee of the Office of War Information. You have no recollection of him?

Mr. DAVIS. No.

Mr. MACHROWICZ. You have no recollection of either Ambassador Ciechanowski or Congressman Lesinski warning you about the fact that these three persons were known Communists, and were in the employ of the Office of War Information?

Mr. DAVIS. I don’t remember that Mr. Lesinski ever warned me about anything. Mr. Ciechanowski, perhaps by his excessive number of warnings, made me forget which particular ones he especially spoke about.

Mr. MACHROWICZ. Would it refresh your recollection if I told you that you told Ambassador Ciechanowski to keep away from that matter?

Mr. DAVIS. I don’t know, but I do know that I was often tempted to tell various of the representatives of the governments in exile to stay out of our business, because almost every one of them seemed to think that it was our duty to carry out the policies of his government and not those of the United States. There were only two exceptions to that, that I can remember, of the governments in exile, the Czechs, that is, the good Czechs, Beneš, and Masaryk and the Filipino Government. I will anticipate your next question. Mr. Hofmeister [Correct spelling: Hoffmeister], who was head of our Czechoslovak desk in New York, after the Communists seized power, became a Communist and is now, I believe, the Czechoslovak Ambassador in Paris. But he showed no signs of that inclination while he was with us that I ever heard of.

Mr. MACHROWICZ. You took that attitude, even though they had warned you of the presence of Communist agents in the Office of War Information?

Mr. DAVIS. If I had taken seriously all of the stories about agents of the Communists in the Office of War Information I would have had nothing else to do but to fire the whole staff. We investigated everything as much as we could, and we found that 99 percent of the allegations were without foundation. I remember that at one time I received a very serious warning in the summer of 1944 about some of our people in Hollywood who were associating with a dangerous and subversive character who at that time happened to be the chairman of the Dewey committee in Hollywood, and who had also written the most effective anti-Communist picture that was ever put on the screen.

Asked how many OWI employees he had to fire “because of their communistic attitude,” Elmer Davis told the congressional testimony “I think it was about a dozen.” Mira Złotowska, Stefan Arski, Adolf Hoffmeister, Irena Maria Balińska and many other Soviet sympathizers were not fired. It is unclear whether Davis included among those fired John Houseman and his protégé Howard Fast. They were quietly forced to resign or resigned under pressure, Houseman in mid-1943 and fast in early 1944. It was never proven that Houseman had joined the Communist Party. Howard Fast claimed that he joined the Communist Party only after he had left his job with the Voice of America.

1953 Stalin Peace Prize Winner Howard Fast

At the Office of War Information, Howard Fast was VOA’s chief news writer and editor (1943) and one of many Salman-Arski’s colleagues who were easily deceived by Soviet propaganda. After resigning from his VOA job in early 1944, Fast was a Communist Party USA member (from 1944 to 1956), recipient of the Stalin International Peace Prize (1953), and reporter and editor for the party’s newspaper The Daily Worker.[ref]Cold War Radio Museum, “Stalin Peace Prize Voice of America Editor Duped by Soviet Propaganda,” January 29, 2020, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/stalin-peace-prize-voice-of-america-editor-duped-by-soviet-propaganda/.[/ref]

In his memoir Being Red (1990) Fast did not hide that while working on Voice of America broadcasts he got his news about Russia from the Soviet Embassy. There is no doubt that his Soviet handlers were also working for or reporting to Stalin’s intelligence services.

I established contact at the Soviet embassy with people who spoke English and were willing to feed me important bits and pieces from their side of the wire. I had long ago, somewhat facetiously, suggested ‘Yankee Doodle’ as our musical signal, and now that silly little jingle was a power cue, a note of hope everywhere on earth…[ref]Howard Fast, Being Red: A Memoir (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1990), 18-19.[/ref]

In the anthology, Red Diapers: Growing Up in the Communist Left, published in 1998, Howard Fast’s daughter, Rachel Fast Ben-Avi, wrote:

People at the Office of War Information, where he worked, drew him and my mother into the Cultural Section of the Communist Party.[ref]Fast Ben-Avi, Rachel. “A Memoir” in Red Diapers: Growing Up in the Communist Left, edited by Judy Kaplan and Linn Shapiro (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 126.[/ref]

She observed that her parents devoted themselves to the Party for the next twelve years, and it became their entire life.

Rachel Fast Ben-Avi recalled that the Roosevelts had invited her father and mother to a luncheon at the White House on January 19, 1945. Her father, she pointed out, was famous and admired, and “Eleanor Roosevelt loved his books.”

Stefan Arski’s Friend Mira Złotowska

Salman-Arski also worked with other socialists, communists, and Soviet sympathizers among radically left-wing journalists at the Office of War Information and the Voice of America. One of them was his presumed romantic partner Mira Złotowska, later known as Mira Michałowska, who published books and articles in English as Mira Michal and used several other pen names. They all produced U.S. government anti-Nazi propaganda pamphlets and Voice of America radio broadcasts, while also helping to spread Soviet propaganda and censoring news about Stalin’s atrocities.

While not the most important among pro-Soviet propagandists at the Voice of America during the war, Salman-Arski’s colleague, Mira Złotowska-Michałowska also returned to Poland, married a high-level communist diplomat, and for many years supported the regime in Warsaw with soft propaganda in the West. She also helped to expose Polish readers to American culture through her magazine articles and translations of American authors. One of the American writers she translated was her former VOA colleague and friend, the 1953 Stalin Peace Prize winner Howard Fast.

A high-level Polish defector, General Izydor Modelski, a former military attaché at the communist regime’s embassy in Washington, testified in April 1949 before the House Subcommittee on Un-American Activities that he became convinced Professor Złotowski, who may or may not have been still Mira Złotowska’s husband at that time, was in charge of the Warsaw regime’s intelligence unit attempting to acquire in 1946 atomic secrets in the United States. General Modelski, who was a highly-respected military officer in the Polish Army before the war, and fought against the Soviets in the 1920 war, and opposed the 1926 military coup in Poland, told the House subcommittee that he had informed the United States intelligence service that Złotowski “is a Communist,” that “he is a scientist” and that his visit to the United States “is not a diplomatic trip.” Modelski, who immediately after his arrival in the United States in 1946 started to cooperate secretly with the U.S. intelligence service, said he was quite sure Złotowski was a spy, but he did not know whether any intelligence information gathered by him was passed directly to Poland or to Russia. He speculated that it could have been sent both to Warsaw and to Moscow. U.S. atomic program secrets would have been far more useful to Russia than they would be to Poland, which was never going to have atomic weapons.

How much Mira Złotowska knew about her husband’s or ex-husband’s alleged spying activities in the United States, or if she knew about them at all, cannot be determined from any documents I have seen. In another congressional testimony, which he gave in May 1949 before the Senate Subcommittee on Immigration and Naturalization of the Judiciary Committee, General Modelski described Professor Złotowski as “a prominent Communist” and “a great scientist” who in 1946 became deputy to Polish communist ambassador in Washington Professor Oskar Lange, a known KGB asset.

Mira Złotowska returned to America in the 1960s as Mira Michałowska, the wife of the ambassador of the Polish People’s Republic, and became an active diplomatic hostess in New York and in Washington. She was described in an article inserted by a member of Congress in the Congressional Record in 1968 as “a thoroughly modern Mata Hari,” a reference to the famous courtesan who was executed in France during World War I on charges of spying for Germany.[ref]John R. Rarick, “The ‘Untouchable” Parade,” 114 Cong. Rec. (Bound) – Volume 114, Part 3 (February 8, 1968 to February 22, 1968), Extension of Remarks, February 5, 1968, in the House of Representatives, Thursday, February 8, 1968, 2860-2861, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1968-pt3/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1968-pt3-1-2.pdf.[/ref] U.S. Congressman who inserted accusations against former U.S. Ambassador to Poland Jacob Beam and Mira Michałowska into the Congressional Record was ultra-conservative, strongly anti-Soviet and anti-communist Democrat from Louisiana Rep. John R. Rarick, a decorated World War II veteran but also a segregationist. He did not want Beam to be U.S. Ambassador to Moscow and on 1969 repeated his warnings on the floor of the House of Representatives about Beam’s alleged earlier romantic relationship with Mrs. Michałowska.[ref]John R. Rarick, 115 Cong. Rec. (Bound) – Volume 115, Part 3 (February 5, 1969 to February 21, 1969), “Untouchables Undaunted” – Jacob Beam in the House of Representatives, February 5, 1969, 2970-2973, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1969-pt3/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1969-pt3-1-2.pdf.[/ref]

Whether Mira Michałowska was spying or not, she was definitely involved in the ultimately unsuccessful business of trying to split the Polish-American community. Her ability to manipulate U.S. government officials and members of Congress into offering more support for the communist regime in Warsaw and limiting or eliminating support for Radio Free Europe and dissidents behind the Iron Curtain was probably a more real danger to Americans than any possible spying activities. In her “Between the Lines” column, quoted in the Congressional Record, American newspaper commentator Edith Kermit Roosevelt, granddaughter of President Theodor Roosevelt, described Michałowska as “a Warsaw charmer” whose “various marriages” and activities “may provide the incentive that could force the issue of Communist espionage and policy manipulation into the limelight.” Edith Kermit Roosevelt noted that White House and State Department circles remained silent about Ambassador Beam and Mrs. Michałowska. She reported being told that they feared that “the revelations could spark ‘a new wave of McCarthyism in the United States.’” In 1967, the columnist asked the National Archives in a letter for information about Stefan Arski’s OWI personnel records. She received a reply that there were no records for Stefan Arski. She and presumably the National Archives staff did not know that his OWI personnel records were under the name of Artur Salman, his real and legal name. Edith Kermit Roosevelt was trying to ascertain whether Mira Michałowska and Stefan Arski were married. On his 1943 OWI federal job application, he listed Magdalena M. Salman as his wife. On the 1946 State Department federal job re-application, Magdalena M. Salman is no longer listed as his wife. If Złotowska and Salman-Arski were romantically involved at one time, I have seen no document confirming that they entered into a legal marriage.

Propaganda For “People’s Poland”

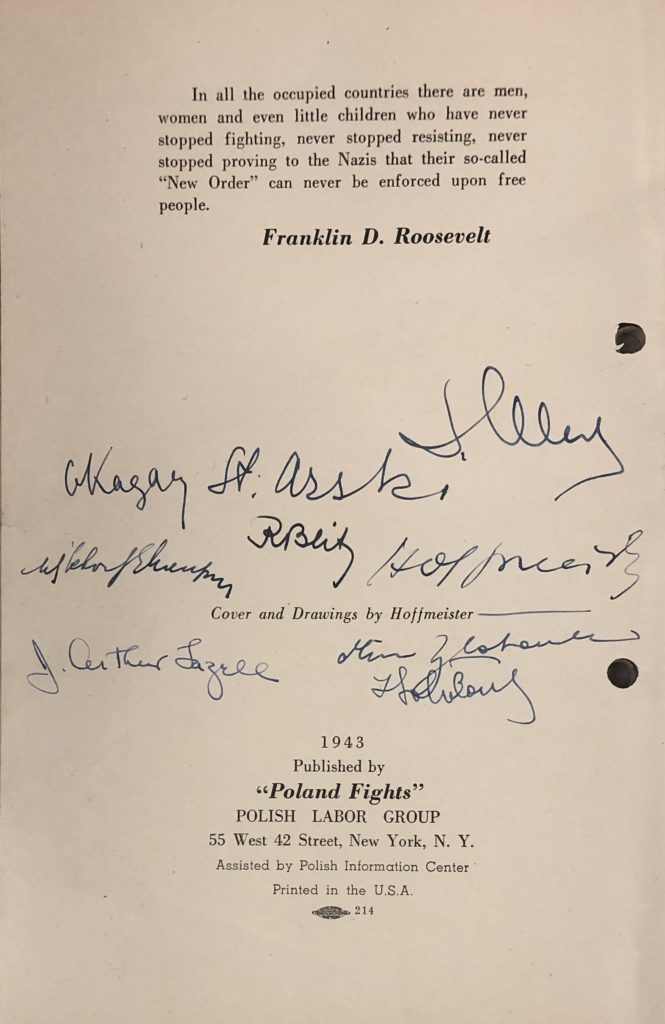

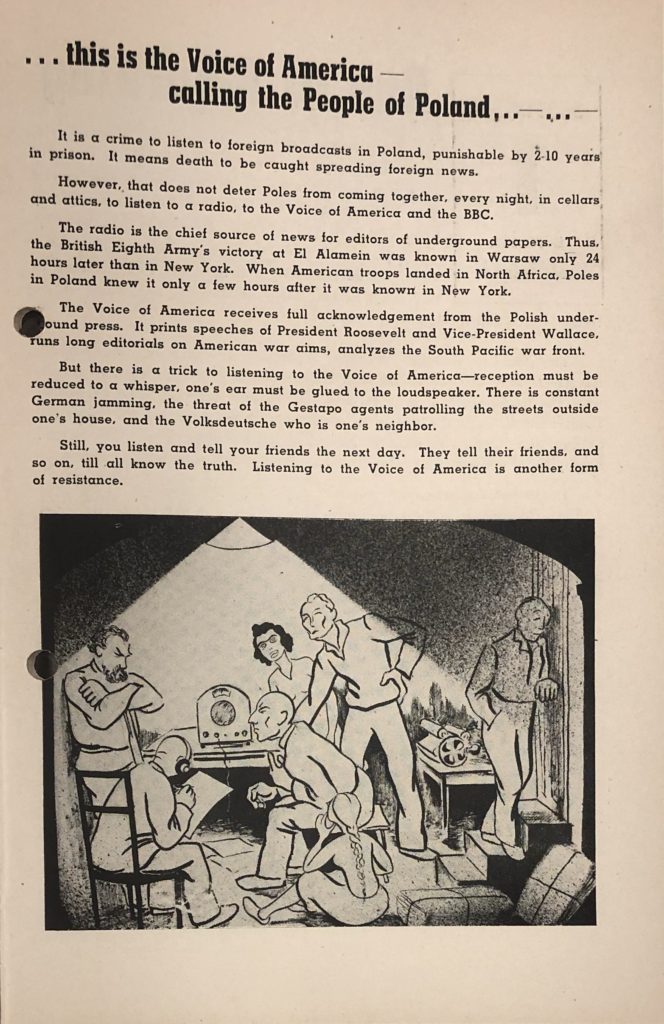

Salman-Arski, Złotowska-Michałowska, and Adolf Hoffmeister, the head of the Voice of America Czech desk, cooperated in 1943 on producing an English-language propaganda booklet targeting Americans, in which they advocated establishing “People’s Poland” and imposition of “democratic control of a planned economy and industry.“ The socialist ideas presented in the pamphlet were the same as those advocated by Professor Oskar Lange.

The pamphlet was not ostensibly in favor of Soviet rule and full Soviet communism. It called for “a free, independent and democratic Poland,” but it included a Marxist call for “a just distribution of the national income and work as the only title to a share of this income.” The 1943 pamphlet was officially published not by the Office of War Information but by a Polish socialist organization in New York supported by OWI. The pamphlet was also then supported by the Polish government-in-exile in London. It was published before Mira Złotowska and Oskar Lange openly declared their loyalty to the communist government in Poland, backed by Soviet Russia. A copy of the pamphlet found in Mira Złotowska’s Office of War Information official personnel file was signed by her, Stefan Arski and Adolf Hoffmeister. In addition to describing the harsh reality of Nazi occupation and advocating for a Marxist socialist system in Poland after the war, the booklet also included a description of wartime Voice of America broadcasts with a number of false and exaggerated claims about their content and effectiveness.

The vast majority of Poles living under German or Soviet occupation and those who were refugees were against communism and any Soviet role in governing Poland after the war. While Voice of America radio broadcasts had some news value on topics not related to Russia, patriotic Poles found most of the broadcasts useless and the pro-Soviet tone offensive. This is how one Polish refugee radio journalist, Czesław Straszewicz, who worked in London during the war and listen to VOA broadcasts, described them in an article published in France in 1953:

“With genuine horror we listened to what the Polish language programs of the Voice of America (or whatever name they had then), in which in line with what [the Soviet news agency] TASS was communicating, the Warsaw Uprising was being completely ignored.”

I remember as if it were today when the (Warsaw) Old Town fell [to the Nazis] and our spirits sank, the Voice of America was broadcasting to the allied nations describing for listeners in Poland in a happy tone how a woman named Magda from the village Ptysie made a fool of a Gestapo man named Mueller.[ref]Czesław Straszewicz, O Świcie,” Kultura, October, 1953, 61-62. I am indebted to Polish historian of the Voice of America’s Polish Service Jarosław Jędrzejczak for finding this reference to VOA’s wartime role. [/ref]

VOA Founding Father Robert E. Sherwood

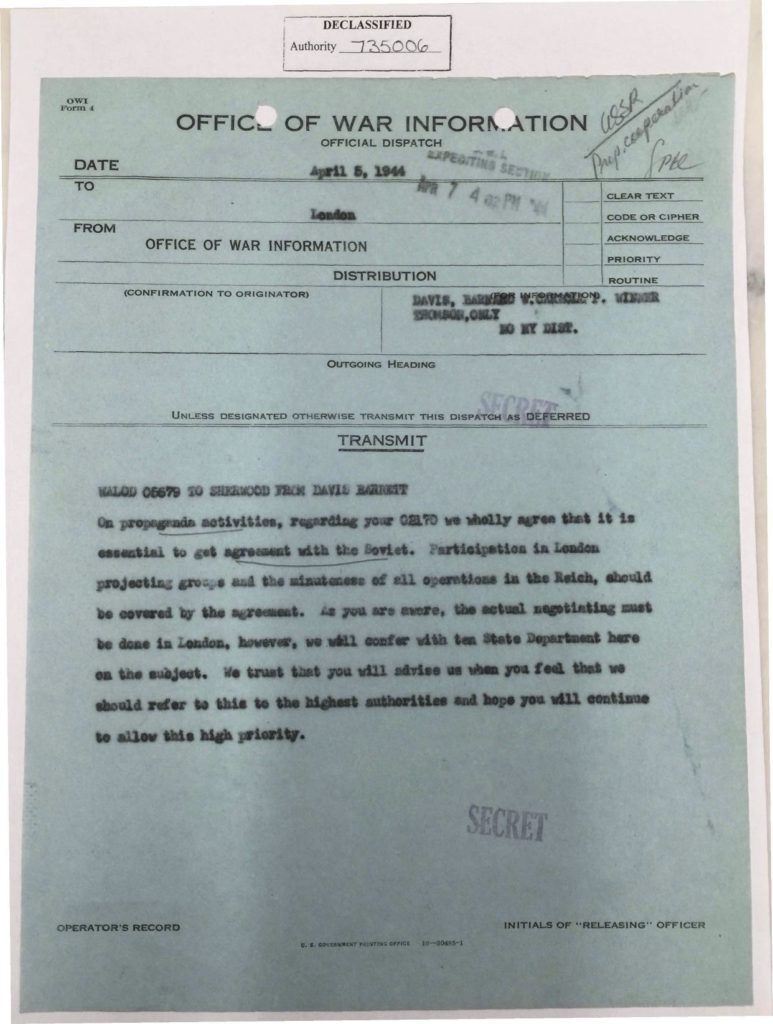

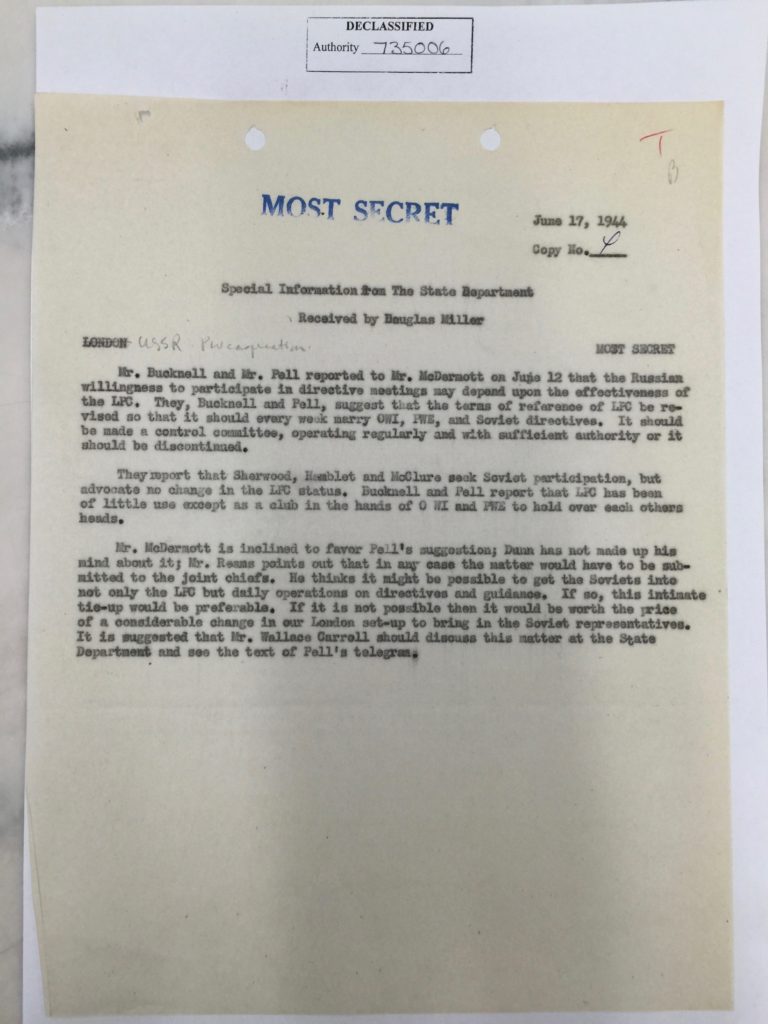

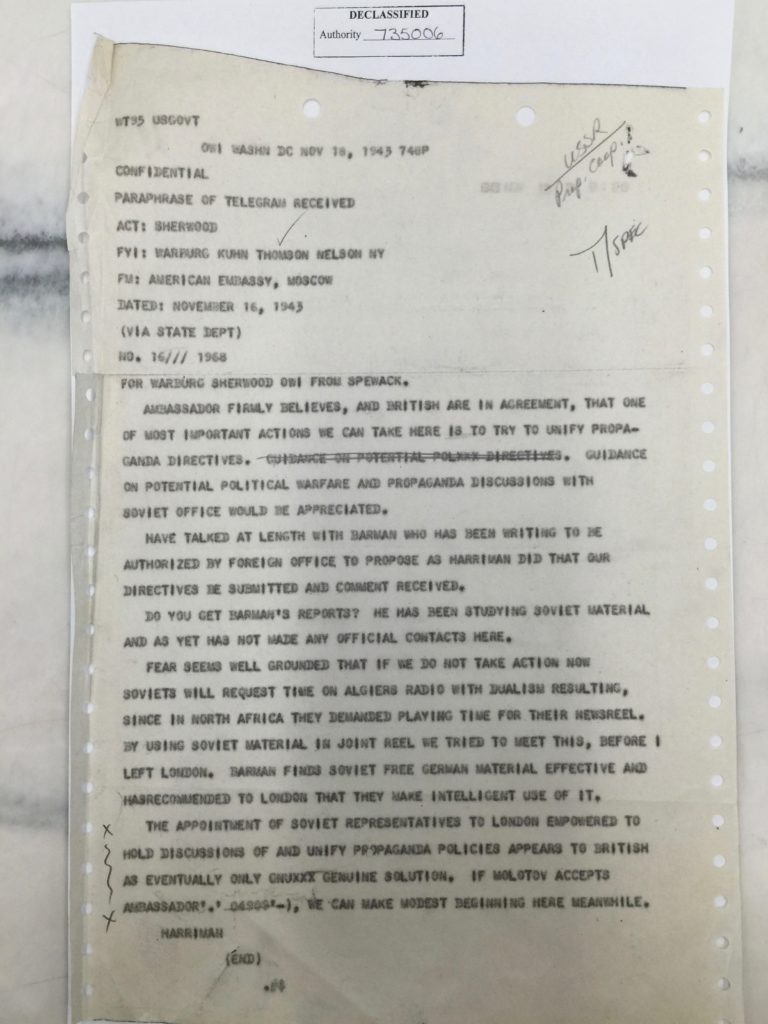

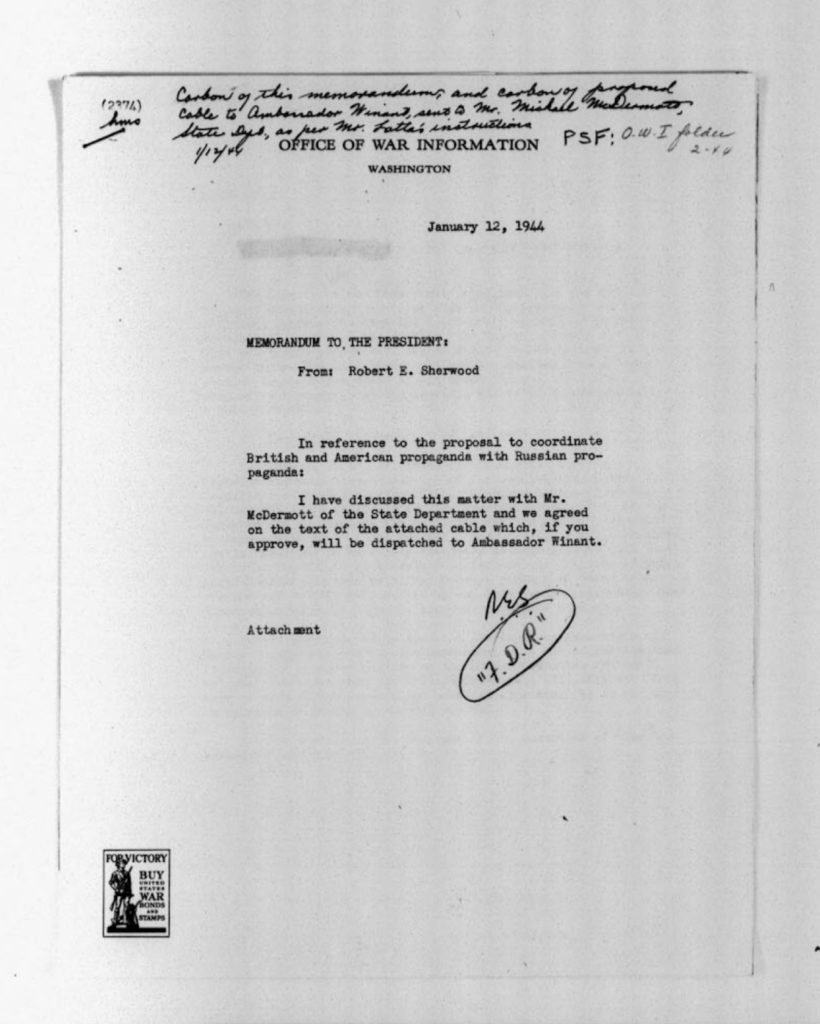

One of many enthusiastic supporters of the Lange-Orlemanski mission to Moscow was President Roosevelt’s speechwriter Robert E. Sherwood. He was also a key OWI official described as the “founding father” of the Voice of America. In 1944, Sherwood was sent to Great Britain to coordinate American propaganda with Soviet Embassy officials in London. He supported coordination of U.S. and Soviet propaganda, as did President Roosevelt’s ambassador to Moscow Averell Harriman.