Despite similarities between Katyn and Bucha, Voice of America is not commenting

April 13 marks the Day of Remembrance for the Victims of the Katyn Massacre – the brutal killing by the Soviet security service NKVD of nearly 22,000 Polish military officers in 1940 when Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany were still allies after their joint attack and occupation of Poland in 1939, which started World War II.

Recently, some Western politicians, news organizations, and social media users have made comparisons between the Soviet propaganda lies about the Katyn murders and the Russian government’s current denials of war crimes committed by Russian soldiers in Bucha and in other towns and cities in Ukraine. Slovenian Prime Minister Janez Janša tweeted that the Russian army behaved in Ukraine “as a horde of KGB executioners at Katyn.”

However, should the Voice of America report on the anniversary of the announcement of the 1943 discovery of the Katyn graves (VOA English News website has so far not mentioned comparisons between Katyn and Bucha), it is doubtful that today’s VOA reporters and editors will admit that from 1943 until 1945 VOA officials and journalists promoted the Soviet Katyn lies and later, at different times, tried to limit reporting about the Soviet responsibility for this war crime.

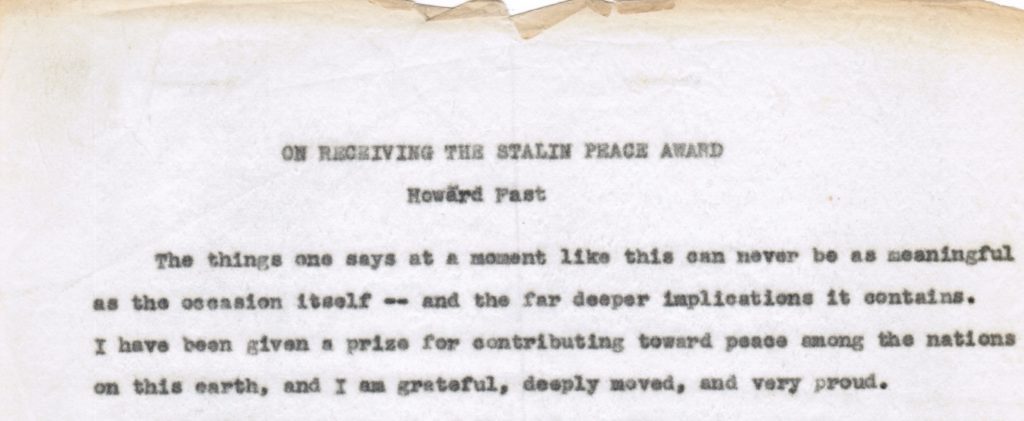

In a recent panel discussion, former VOA director Sanford Ungar admitted somewhat reluctantly in response to a question that VOA’s first chief English news writer and editor, Howard Fast, was a pro-Kremlin Communist Party activist, who after leaving VOA in 1944 received the 1953 Stalin Peace Prize.

Ungar, who heads the Free Speech Project at Georgetown University, implied that such information about Fast’s pro-Soviet propaganda at VOA may “amuse” and suggested that even asking questions about it may be a form of McCarthyism.

Millions of Stalin’s victims, including those from Ukraine and their relatives, may not agree with Mr. Ungar that talking about VOA’s Stalin Peace Prize winner is amusing, but Mr. Ungar deserves some credit for being the first Voice of America director to acknowledge that Howard Fast did work for VOA.

Current Voice of America officials, editors, and journalists have not made comparisons between Katyn and Bucha because they either do not know enough history or they are ashamed to admit that their predecessors were duped by Soviet propaganda and promoted the Soviet lies about Katyn. If they were not afraid to talk about this topic, they could point out, however, that refugees from communism hired by the Voice of America after the end of World War II replaced pro-Soviet VOA propagandists. The anti-communist refugee journalists tried hard to get the management to change its policies on reporting on Soviet atrocities and found many allies among both Republicans and Democrats in Congress. The Truman administration carried out the initial reforms at the Voice of America. Extensive VOA reporting about the Katyn massacre started in 1951-1952. All remaining restrictions on VOA reporting about Katyn were removed during the Reagan administration in the 1980s.

VOA officials and journalists were manipulated by the Soviet fake news offensive for many years

By Ted Lipien for Cold War Radio Museum

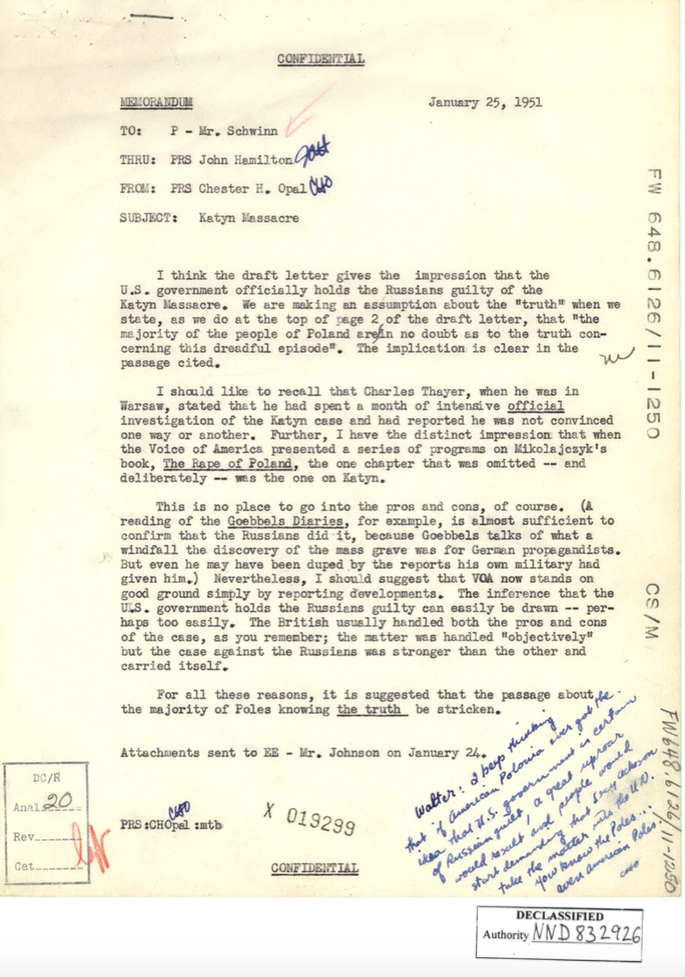

According to a declassified confidential State Department memorandum dated January 25, 1951, Charles Thayer, who from January 1948 to October 1949 had been the Voice of America (VOA) director and who in 1947 was in charge of launching the first VOA Russian broadcasts (VOA did not broadcast in Russian earlier to avoid offending Stalin), was uncertain after World War II whether the Russians were the actual perpetrators of the 1940 Katyn massacre of about 22,000 Polish POWs, most of them military officers. The confidential memorandum, which revealed this information, was written by U.S. diplomat Chester H. Opal, who had served in Warsaw after World War II as Information Officer from 1946 to 1949. It was addressed to Walter Schwinn, who also had served at the U.S. Embassy in Poland.

In his confidential and later declassified memorandum, Opal discussed Voice of America’s reporting on the World War II massacre of members of the Polish military and intellectual elites carried out in April and May 1940 by the Soviet NKVD secret police in Katyn near Smolensk and in several other locations in the Soviet Union. At the time of the murders, Stalin’s Russia was still an ally of Hitler’s Nazi Germany after the two totalitarian regimes invaded and divided Poland in 1939 and started the Second World War.

During and after the invasion and later the occupation and the annexation of the eastern part of pre-war Poland, the Soviets detained Polish officers and arrested government officials. Among the detained reserve officers were journalists, writers, university professors, teachers, physicians, and lawyers. All information about these prisoners ceased after April and May 1940. At first, some mail was allowed to reach the POWs, but after the spring of 1940, letters sent to them from Poland were returned by the Soviet post office marking that addressees could not be found. When the German army discovered the mass graves in the spring of 1943 with the bodies of several thousand Polish officers, Soviet officials with the help of their propagandists, and a number of pro-Soviet Western journalists including many at the Voice of America, accused the Germans of committing the Katyn murders.

The families of the imprisoned men also became victims of fake news reporting. The Soviet authorities arrested and deported to Gulag labor camps parents, wives, and children of many of the Polish officers. Hundreds of thousands were deported. Many of them, especially the elderly and the children, died from hunger, illnesses, and lack of medical care. If the truth about Katyn could not be told by the Voice of America for many years, the story of their families deported to the Gulag slave labor camps also could not be told. Those who survived their captivity became silenced refugees, even in the West. They were an inconvenient proof of Soviet cruelty, which interfered with efforts by pro-Soviet VOA writers to support the establishment of a pro-Moscow governments in Eastern Europe.

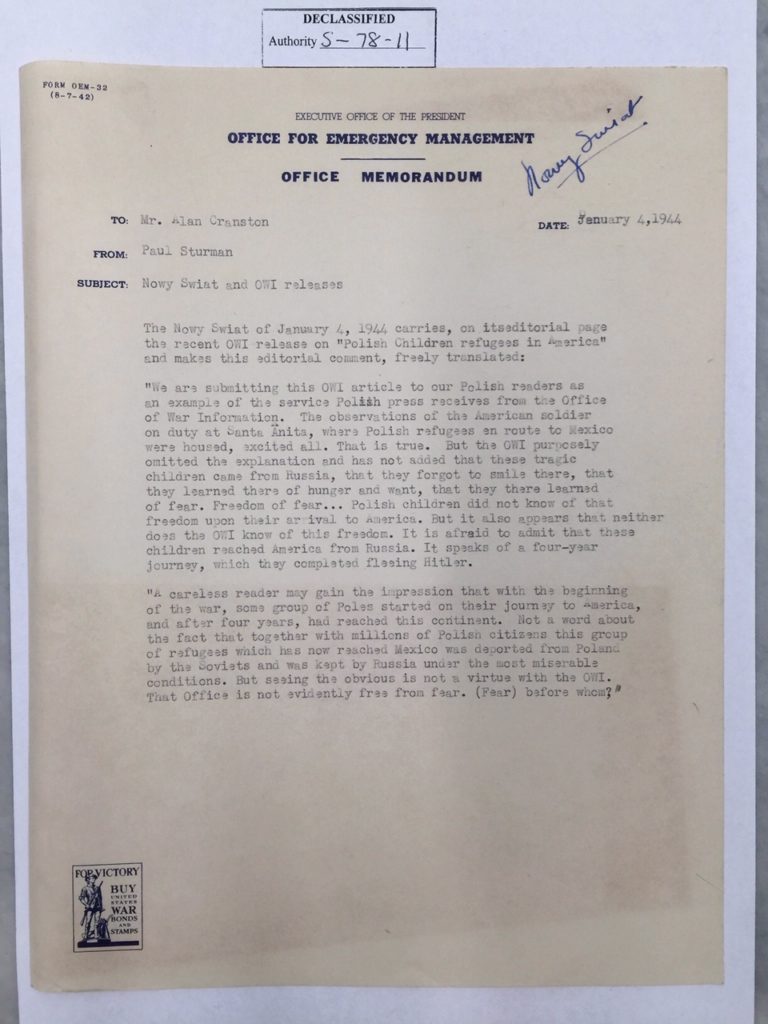

When some of the survivors, including thousands of orphan children, were able to leave the Soviet Union in 1942 and became refugees after Stalin had released them following Hitler’s attack on Russia, the Office of War Information (OWI), the parent government agency of the Voice of America during World War II, spread deceptive information about them to protect the Soviet dictator’s reputation in the United States. President Roosevelt referred to him as “Uncle Joe.” OWI officials also tried to censor Polish-American radio stations and newspapers to prevent them from reporting Soviet atrocities.[ref]Ted Lipien, “Polish children refugees – Time and OWI/VOA propaganda,” Silenced Refugees, https://silencedrefugees.com/polish-children-refugees-time-and-owi-voa-propaganda/. Accessed May 3, 2021.[/ref] In order to block media access and publication of negative stories about life in the Soviet Union, American officials in charge of a group of Polish refugee orphans who had arrived in the United States in 1943 after fleeing Russia put them in a former detention facility for Japanese Americans at the Santa Anita U.S. Army training camp near Los Angeles. After a few days of quarantine, they promptly dispatched the entire group to Mexico under military guard to prevent contact with journalists and ordinary Americans during the trip. To avoid negative publicity in the United States for the Soviet ally against Nazi Germany, the Roosevelt administration helped to pay for their trip to Mexico where they were placed in a refugee camp under an agreement reached earlier between General Władysław Sikorski, Prime Minister of the Polish government in exile in London, and the Mexican government. Polish American families were not permitted to adopt them. As the Office of War Information lied to Americans about victims of Stalin’s repression, it also produced propaganda films justifying the internment of Japanese American U.S. citizens.[ref]Ted Lipien, “How the Roosevelt Administration Shipped Polish Refugee Orphans to Mexico In Locked Trains and Lied About It to Protect Stalin: The Untold Story of Polish Refugee Children from Soviet Russia: ‘A Group Lost in History’,” Cold War Radio Museum, December 9, 2018, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/how-u.s.-shipped-polish-refugee-orphans-from-russia-to-mexico-in-locked-trains-and-lied-about-it-to-protect-stalin/.[/ref]

READ: How the Roosevelt Administration Shipped Polish Refugee Orphans to Mexico In Locked Trains and Lied About It to Protect Stalin: The Untold Story of Polish Refugee Children from Soviet Russia: ‘A Group Lost in History’

While some senior U.S. State Department diplomats knew that the Soviets were lying about Katyn, as well as deportations and other atrocities, World War II Voice of America officials and VOA’s pro-Soviet journalists accepted Stalin’s propaganda lie. Some continued to support it even for several years after the war.

Photos by: Lieutenant Colonel Henry I. Szymanski, U.S. Army

Source: The Katyn Forest Massacre: Hearings Before The Select Committee to Conduct An Investigation on The Facts, Evidence and Circumstances of the Katyn Forest Massacre; Eighty-Second Congress, Second Session On Investigation of The Murder of Thousands of Polish Officers in The Katyn Forest Near Smolensk, Russia; Part 3 (Chicago, Ill.); March 13 and 14, 1952 (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1952), pp. 459-461.

“I should like to recall that Charles Thayer, when he was in Warsaw, stated that he had spent a month of intensive official investigation of the Katyn case and had reported he was not convinced one way or another.”[ref]January 25, 1951 memorandum from Chester H. Opal to Mr. Schwinn. Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, 1763 – 2002. Series:Central Decimal Files, 1910 – 1963. File Unit: [648.6126/8-2950 – 648.6126/2-2952. Item: Letter from Mrs. James F. Connors Regarding the Voice of America Broadcast on the Katyn Forest Massacre and Related Documents, 12/12/1950. National Archives at College Park, 8601 Adelphi Road, College Park, MD 20740-6001. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/6850483.[/ref]

The evidence of the Russian guilt was overwhelming to any Russia expert who studied the history of Stalinist terror but not to many Voice of America officials, some of them prominent American journalists who were blinded by Soviet propaganda and/or corrupted with the help of the Soviet secret police and its agents. Some although not all U.S. diplomats also accepted the Soviet narrative on Katyn. The best ones were not fooled, but even after the war, State Department Foreign Service Officer and VOA director Charles Thayer apparently found it impossible to believe that Joseph Stalin could have committed such a crime as the murder of thousands of Polish war prisoners in Soviet captivity. The total number of Polish POWs executed by the Soviets in the spring of 1940 is now estimated to be nearly 22,000 from several mass murders sites. Those who had died at Katyn had their hands tied with rope or wire, an African American journalist Homer Smith, who had witnessed the Soviet exhumation of the bodies in 1944, wrote in his book Black Man in Red Russia published in Chicago in 1964.[ref]Homer Smith, Black Man in Red Russia (Chicago: Johnson Publishing Company, 1964), 162.[/ref]Before returning to the U.S. via Ethiopia with the help of the CIA in 1962 after he cut his ties with the Soviet regime, Smith had lived in Moscow since 1932 and under the pseudonym of “Chatwood Hall” sent Soviet propaganda press releases to the United States, especially to the Associated Negro Press (ANP) and the Baltimore Afro-American.[ref]Thomas Urban, The Katyn Massacre 1940: History of a Crime (Yorkshire – Philadelphia: Pen & Sword Books Ltd), 123.[/ref]

Those killed in Katyn and at other locations with a shot in the back of the head and through other forms of executions, included an admiral, two generals, 24 colonels, 79 lieutenant colonels, 258 majors, 654 captains, 17 naval captains, 3,420 NCOs, seven chaplains, three landowners, a prince, 43 officials, 85 privates, and 131 refugees. Also, among the dead were 20 university professors; 300 physicians; several hundred lawyers, engineers, and teachers; and more than 100 writers and journalists as well as about 200 pilots, including one woman pilot, Janina Antonina Lewandowska (22 April 1908 in Kharkiv – 22 April 1940 in Katyn) the only female murdered in the Katyn Forest.[ref]Nataliya Lebedeva, “The Tragedy of Katyn,” International Affairs (Moscow), June 1990 and “The Katyn Controversy: Stalin’s Killing Field”. Studies in Intelligence. CIA (Winter). https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/csi-publications/csi-studies/studies/winter99-00/art6.html. Retrieved 13 April 2018.[/ref]

In his 1964 book, Smith who had left America in 1932 because of racial violence against Blacks but became disillusioned with Russian communism after his friend Lovett Fort-Whiteman, an African American communist from Chicago, disappeared into the Gulag and later died from malnutrition and mistreatment, noted numerous doubts about the Soviet investigation of the Katyn murders. He wrote them down in his reporter’s notebook in 1944:

“Why have no foreign newsmen been invited to be present when the opening of the grave began? Why had we not been permitted to be present when the first autopsies were performed? Why had Stalin not invited any allied or neutral experts to join the Soviet Investigative team?”[ref]Homer Smith, Black Man in Red Russia (Chicago: Johnson Publishing Company, 1964), 164.[/ref]

Knowing that he was not able to publish the truth without disappearing in the Gulag or worse, to his credit, he did not file any report on his trip to Katyn, while many of the other correspondents did and supported the Soviet Katyn lie. It was for Homer Smith “the most ghastly and shocking sight” he saw during the war in Russia. He wrote in 1964:

“I happen to be one of the few foreigners, and the only Negro, to have visited the scene of the macabre murder of some eleven thousand Polish Army officers, and still have vivid memories of the scene of the savage slaughter in the dreamy spruce forest of Katyn near Smolensk.”

Homer Smith, Black Man in Red Russia (Chicago: Johnson Publishing Company, 1964), p. 158.

I happen to be one of the few foreigners, and the only Negro, to have visited the scene of the macabre murder of some eleven thousand Polish Army officers, and still have vivid memories of the scene of the savage slaughter in the dreamy spruce forest of Katyn near Smolensk.[ref]Homer Smith, Black Man in Red Russia (Chicago: Johnson Publishing Company, 1964), 158.[/ref]

Homer Smith, Black Man in Red Russia (Chicago: Johnson Publishing Company, 1964), 158.

Before Charles Thayer was named Voice of America director, while he was in charge of launching the first VOA Russian broadcast in 1947 he recruited as a volunteer a former Office of War Information (OWI) journalist Kathleen Harriman who like him came from a socially prominent American family.[ref]Charles W. Thayer, Diplomat (London: Michael Joseph, 1959), 187.[/ref] She was one of the more than a dozen Western journalists who went to Katyn in January 1944 at the invitation of the Soviet government and were expected to confirm the Soviet lie that the Germans committed the mass murder. Almost all of them did, including Ms. Harriman and United Press Moscow correspondent Harrison Salisbury, later a Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times correspondent who even in the 1980s wrote that he was still not absolutely sure whether the Germans or the Soviets were responsible for the deaths in Katyn. Had he reported the truth in 1944, the Soviet censors would not have allowed his report to be sent from Moscow, and he would have been expelled from Russia. Had he taken a firm position on Katyn in the 1980s, as any honest journalist should have, and stated that it was a Soviet crime, he could have had problems getting a Soviet visa for his next trip to Russia.

The power of Soviet propaganda on Katyn was reinforced by blackmail and intimidation of Western reporters, which many of them could not or did not want to resist. One prominent American journalist who during World War II did not fall for Soviet propaganda on Katyn was Edward R. Murrow, who was based in London and cultivated sources among London-based officials of the Polish government in exile. Murrow later served as the director of the United States Information Agency (USIA), which was then the parent federal agency for the Voice of America, during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations.[ref]Ted Lipien, “Edward R. Murrow Would Not Have Approved of Partisan or Chinese Communist Propaganda at Voice of America,” BBG Watch, October 11, 2020, https://bbgwatch.com/bbgwatch/edward-r-murrow-would-not-have-approved-of-partisan-or-chinese-communist-propaganda-at-voice-of-america/.[/ref]

Kathleen Harriman, who later used her married name, Mortimer, was despite her young age one of the key helpers in spreading Stalin’s lie about Katyn within the U.S. government. Although she was young, she had some credibility because of her journalistic credentials through her occasional work for the Office of War Information, some of which could have made it into Voice of America radio reports. She was also the daughter of the U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union and through him submitted a nine-page written report to the State Department in Washington in which she stated that despite some questions about the evidence presented by Soviet officials of the so-called Burdenko Special Commission, named after Soviet professor of medicine Nikolai Burdenko, in her opinion and in the opinion of other Western journalists who went with her to Katyn, the murders were carried out by the Germans. She had worked for the Office of War Information in London but came to Russia to accompany her father, W. Averell Harriman, after he became President Roosevelt’s ambassador to the Soviet Union. At the U.S. Embassy, she continued to do volunteer work for OWI. At the request of her father, she went to Katyn in January 1944 with a group of Western reporters on a trip organized by the Soviet authorities after the area where the mass graves were located was liberated by the Red Army.

For their trip to Katyn, the Soviet Foreign Ministry arranged a luxury train and provided plenty of vodka, Crimean champagne, caviar, and a rare luxury item under communism, toilet paper for the train’s clean bathrooms.[ref]Thomas Urban, The Katyn Massacre 1940: History of A Crime (Yorkshire – Philadelphia: Pen and Sword Books Ltd, 2020), 127.[/ref] Despite abundant evidence that this was an NKVD-run Soviet propaganda operation designed to mislead them and through them to mislead Western publics, she and almost all of the other journalists reported after the trip that the Germans were responsible for the murders. While a few of the Western correspondents did not state their outright support for the Soviet position on Katyn, none wrote that Soviet officials were lying although privately some were reportedly convinced that they were being fed lies.[ref]Krystyna Piórkowska, English-Speaking Witnesses to Katyn: Recent Research (Warsaw: Museum Wojska Polskiego, 2012), 102-108.[/ref]

To report the truth would have been the end of their work as war correspondents in the Soviet Union, and could have had even more unpleasant consequences. It was a classic example of the ability of the Soviet government and its secret police to intimidate journalists and corrupt their reporting. Reporters who went with Kathleen Harriman to Katyn, witnessed the Soviet autopsies, saw falsified evidence, and still reported that the Germans were responsible for the murders included United Press (UP) and future New York Times correspondent Harrison Salisbury, BBC and Sunday Times correspondent Alexander Werth, Time correspondent Richard Lauterbach, Toronto Star correspondent Jerome Davis, The Times of London correspondent Ralph Parker, Christian Science Monitor correspondent Edmund Stevens, and Daily Worker (Communist Party, U.S.) correspondent John Gibbons. It was through these journalists and others, including those working for the Office of War Information and the Voice of America, that Western public opinion was deceived about Katyn and the true nature of the Stalinist regime in Russia. VOA broadcasts also carried the deception to an international audience.

To their credit, among the reporters who went to Katyn to witness the Soviet propaganda show, Reuters correspondent Duncan Hooper, Associated Press (AP) correspondent Henry C. Cassidy, and young New York Times correspondent, 28-year-old William H. Lawrence, reported only what they saw and did not conclude that the Soviets were innocent, and the Germans were guilty. Thomas Urban, a correspondent for the major German daily Süddeutsche Zeitung, described in his book, The Katyn Massacre 1940: History of A Crime, in some detail the failure as journalists of most of the other Western reporters. He also noted that Kathleen Harriman “led a privileged life in Moscow and had an unrealistically positive image of the everyday life of the Russian population.”

…the accounts of Jerome Davis, Richard Lauterbach, Edmund Stevens and Alexander Werth shaped the opinion of the Anglo-American public. The Katyn reports of the four pro-Soviet correspondents were later reprinted by the press in the USSR and the People’s Republic of Poland.[ref]Thomas Urban, The Katyn Massacre: History of A Crime (Yorkshire – Philadelphia: Pen & Sword Ltd, 2020), 118-140.[/ref]

Kathleen Harriman later said that she did not file a news report after her Soviet-arranged trip to Katyn in addition to her confidential report sent to the State Department. In 1947, she played only a minor role in the launch of VOA Russian broadcasts, working as a volunteer, but her participation would have sent a message to Moscow that the Voice of America Russian Service under the direction of her personal friend, Charles Thayer, was not going to raise the Katyn issue. Testifying before a congressional committee in 1951, she admitted that she was wrong as a journalist in accepting as true in 1944 the Soviet propaganda lies about the Katyn massacre and said that she no longer thought the Soviets were innocent of the crime, but the harm from her diplomatic report and news reports by American and other Western correspondents who went with her to Katyn was already done.

When Charles Thayer planned and launched the first Voice of America Russian-language program in 1947, it was not exactly what millions of Gulag prisoners in the Soviet Union would have expected to hear from the Free World if they could secretly listen to VOA. According to Edward Carleton Helwick, Jr., who had worked for the Voice of America as an English-language writer-producer and later compared VOA programs in 1947 with those in early 1950-1953, VOA’s first Russian-language broadcast did not include outside the newscast any criticism of Soviet leaders or an analysis of human rights issues under communism.

The first program [Voice of America Russian program in 1947], a widely publicized event, had consisted of a twenty minutes of straight news; a twelve minute lecture on the United States form of government, which said, among other things, that the U.S. had lost its fear of the “so-called despotism of the central government”; an interlude of cowboy tunes, including “The Old Chisholm Trail,” the refrain of which, “coma ti yi soupy, happy yay, happy ya, come ti yi soupy happy yay,” Time observed, “probably sounded like static to Russian ears”; a talk on a new cure for hay fever, revealing that the U.S. had 5 million sufferers; and details of a new method of exploring the Milky Way.[ref]Edward Carleton Helwick, Jr., Policy problems of the Voice of America: 1945-1953. Master Thesis, Department of Political Sciences, University of Southern California, June 1954, pp. 218-219.[/ref]

Helwick also observed that mainstream U.S. media outlets were also not impressed with the direction and tone of the first VOA Russian broadcast.

It was evident from newspaper accounts that the broadcast in America, at least, was received with something less than enthusiasm. Typical of the reactions, the New York World Telegraph headline, “Russians Restrain Joy over U.S. Broadcast.”[ref]Edward Carleton Helwick, Jr., Policy problems of the Voice of America: 1945-1953. Master Thesis, Department of Political Sciences, University of Southern California, June 1954, p. 219. Helwick cites “Let’s Talk to those Russians, ” Time, 49:28, March 3, 1947.[/ref]

In 1950, the Truman White House was also not happy with Voice of America programs after widespread criticism that they were soft on communism and the Soviets. In a foreign policy speech on April 20, 1950, to members of the American Society of Newspaper Editors, President Truman unveiled the “Campaign of Truth”–a multi-faceted U.S. government’s international information policy in response to harsh Soviet propaganda attacks on the United States and its allies. Truman’s address was designed to inspire journalists, including Voice of America’s federal employees of the Department of State who were broadcasting at the time to the world in multiple languages from VOA studios in New York, to offer stronger and more effective resistance to Soviet propaganda and to communist influence.

“Everywhere that the propaganda of the Communist totalitarianism is spread, we must meet it and overcome it with honest information about freedom and democracy,” Truman said. He also alluded to the media’s criticism of his foreign policy, and indirectly to criticism of the Voice of America. “Foreign policy is not a matter for partisan presentation,” Truman said as he outlined his administration’s plan to resist communism and its propaganda with a “Campaign of Truth.”

After President Truman’s “Campaign of Truth” speech on April 20, 1950, Secretary of State Dean Acheson said in his semiannual report to Congress on the International Information and Educational Exchange Program for the period July 1 to December 31, 1950, that “Operationally, launching of the Campaign of Truth was reflected at the outset more in sharpened program content and specialized radio treatment than in marked increases in broadcast operations.”[ref]Dean Acheson, U.S. Secretary of State, “Launching the Campaign of Truth–First Phase: Sixth Semiannual Report of the Secretary of State to Congress on the International Information and Educational Exchange Program, July 1 to December 31, 1950,” Department of State Publication 3479, December 1951, p. 3. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951d03562370p?urlappend=%3Bseq=8.[/ref]

It was obvious from such remarks that Thayer’s tenure as the chief of the Voice of America Russian Service and later VOA director was not viewed by senior Truman Administration officials as effective against communist propaganda. The Truman Administration threw its support behind efforts to launch Radio Free Europe as an ostensibly private initiative but under secret management of the CIA with U.S. government funding. Secretary Acheson was hardly a hawk on the Soviet Union, and was himself accused of being soft on communism by Senator Joseph McCarthy. Acheson was a diplomat, but he was not soft on communism or Soviet aggression and indirectly expressed his disappointment with VOA broadcasts to Russia at the time when Thayer was in charge at VOA, although he did not mention his name. The Stalinist regime was just as murderous in 1947, when the VOA Russian broadcast was finally started under Thayer in charge of the Russian Service, as it was in the second half of 1950, the period covered by Acheson’s report to Congress when Thayer was no longer the Voice of America director. Acheson indirectly agreed with critics that earlier VOA programming to the Soviet Union was not sufficiently well-planned to meet the Soviet propaganda challenge and had to be changed.

In the broadcasts to Eastern Europe, greater program variety was introduced; more liberal use was made of anti-Communist political satires and exposés, and of the documentary and dramatized technique.

The systematic jamming of VOA’s Russian broadcasts greatly influenced both their content and format. Music and dramatizations were eliminated, and the salient portions of the programs were repeated around the clock. Later in the period, when a partial neutralization of the Soviet jamming effort was achieved, some of the dramatized material was restored. An increasing number of Soviet DP’s came to the microphones of VOA to tell their story.[ref]Dean Acheson, U.S. Secretary of State, “Launching the Campaign of Truth–First Phase: Sixth Semiannual Report of the Secretary of State to Congress on the International Information and Educational Exchange Program, July 1 to December 31, 1950,” Department of State Publication 3479, December 1951, p. 4. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951d03562370p?urlappend=%3Bseq=11.[/ref]

Today’s Voice of America management in the U.S. Agency for Global Media (USAGM), the successor to the World War II Office of War Information, presents Charles Thayer as a defender of U.S. international journalism and a victim of Senator McCarthy’s “Red Scare” and does not mention his naïveté, acceptance of Soviet propaganda and failure to recognize fully the danger of Stalinist totalitarianism.

Thayer believed strongly in VOA’s mission, writing in his book Diplomat that international broadcasting and the foreign information program “are essential to our defense. That it will develop into a powerful auxiliary arm of American diplomacy depends on whether its leaders and Congress understand its proper role, its limitations, and its need not for numbers (of Staff) but for qualified personnel.”[ref]Voice of America Public Relations, “Past VOA Directors: Charles Thayer (1948-1949),” July 18, 2018. https://www.insidevoa.com/z/5483.[/ref]

Thayer returned to the Foreign Service after his time at Voice of America, serving in several consular positions in Germany until 1953. He was forced to resign from government service through the efforts of J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI and Senator Joseph McCarthy’s Red Scare and Lavender Scare campaigns. A prolific author, he remains the only VOA director to have written fairly regularly for Sports Illustrated, usually about hunting.[ref]Voice of America Public Relations, “Past VOA Directors: Charles Thayer (1948-1949),” July 18, 2018. https://www.insidevoa.com/z/5483.[/ref]

Charles Thayer was definitely harassed by the FBI over accusations of sexual affairs, homosexual, which he strongly denied, and heterosexual, as well as accusations of financial irregularities, but his failure at VOA was not caused by disloyalty or secret sympathy for communism–charges made by Senator McCarthy falsely and irresponsibly also against many other Americans who were far more competent than Thayer. His failure in his diplomatic and Voice of America work was dangerous in itself because being naive, easily deceived by communist propaganda, and hiding Soviet atrocities from international audiences by an American official at his level may have indirectly cost the lives of Americans and people living behind the iron and bamboo curtains. A declassified CIA report from 1953 featured a claim by a still unidentified Slovak source asserting that some Slovaks lost their lives and freedom because the U.S. government-run Voice of America was broadcasting pro-communist propaganda and continued to downplay Stalinist crimes in radio programs to Czechoslovakia even into the early 1950s despite the drastic change of U.S. policy toward Moscow at the start of the Cold War. Another CIA source said in 1952 that “The greater the number of people listening to VOA, the greater the responsibility of those making these broadcasts.” “A great deal of harm can be done by irresponsible broadcasting,” the CIA source warned.[ref]Central Intelligence Agency, “Slovak Reaction to VOA Broadcasts,” June 17, 1953. Last accessed January 2, 2019, https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP80-00810A001400310007-5.pdf. Also, see: Ted Lipien, “1953 CIA Source: People Died in Czechoslovakia Because of Pro-Communist Propaganda from Voice of America,” Cold War Radio Museum, January 4, 2019, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/listening-to-western-broadcasts-in-communist-ruled-czechoslovakia/.[/ref]

READ: 1953 CIA Source: People Died in Czechoslovakia Because of Pro-Communist Propaganda from Voice of America

During World War II, the Voice of America employed many communist and Soviet sympathizers. There were fewer of them after the war, but VOA broadcasts under Charles Thayer’s leadership were still widely at odds with the expectation of the audiences living under daily communist terror. This made it easier for Senator McCarthy and other critics to come up with false and far-fetched accusations. Some of the criticism preceded Senator McCarthy’s exaggerated charges. In June 1947, during the debate in the House of Representatives, Rep. John Taber (R-NY) said that the Voice of America’s very first broadcast to Russia earlier that year was a “totalitarian philosophy broadcast.” He added, however, that “if it was a bill providing for the Voice of America, and it was honestly to be the Voice of America, I would support it.”[ref]John Taber, 93 Cong. Rec. (Bound) – Volume 93, Part 12 (June 13, 1947 to December 19, 1947), 6965, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1947-pt6/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1947-pt6-2-2.pdf.[/ref] Such criticism of the first Voice of America Russian broadcast was far-fetched, but it was true that under Thayer early VOA Russian broadcasters were not allowed to criticize the Soviet Union, as one of them, Helen Zhemchuzhny Bates Yakobson (1913-2002), noted in her memoir published in 1994.

In those early years, VOA programs attempted to give full and impartial reports of life in the United States, including confessions of our shortcomings and faults. No direct criticism or attacks on the Soviet system were permitted. After all, they had only recently been our allies. But as the Cold War intensified, VOA responded and became openly and vigorously critical of the Soviet system and government.[ref]Helen Yakobson, Crossing Borders: From Revolutionary Russia to China to America (Tenafly, N.J: Hermitage Publishers, 1994), 146.[/ref]

Thayer’s eventual resignation from Foreign Service in 1953 reportedly helped win Senate confirmation of his brother-in-law Charles Bohlen as Ambassador to Russia.[ref]Robert D. Dean, Imperial Brotherhood: Gender and the Making of Cold War Foreign Policy (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001), 133-5; New York Times: “Bohlen’s Relative Quits,” March 27, 1953.[/ref] After Thayer, the VOA Russian Service was headed by Alexander Gregory Barmine, a Red Army general and Soviet intelligence agency GRU officer who had defected to the West in 1937. Barmine was a staunch anti-communist. In 1959, Charles Thayer accompanied former Ambassador W. Averell Harriman on a 6-week tour of the Soviet Union. Had he allowed broadcasts about Katyn when he was the head of the VOA Russian Service and later VOA director, he would most likely not have received a Soviet visa.

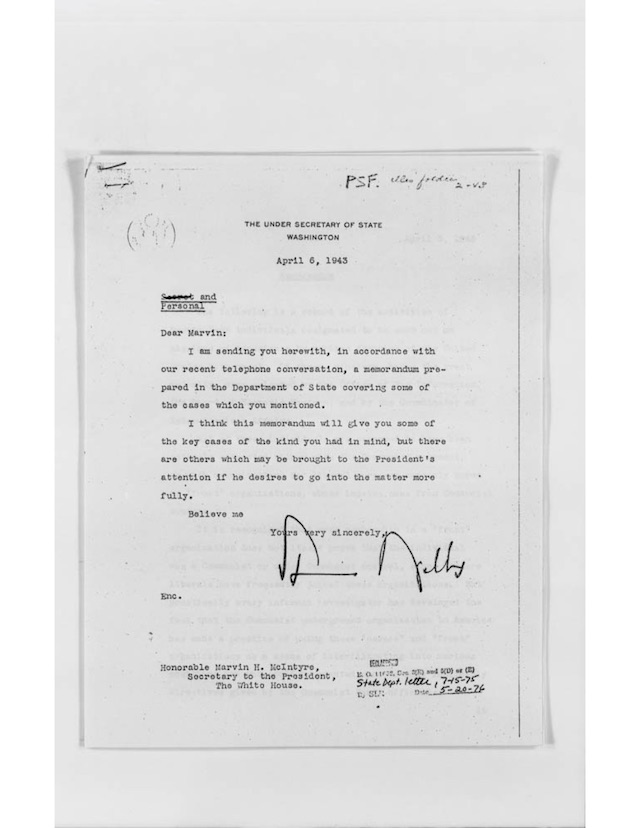

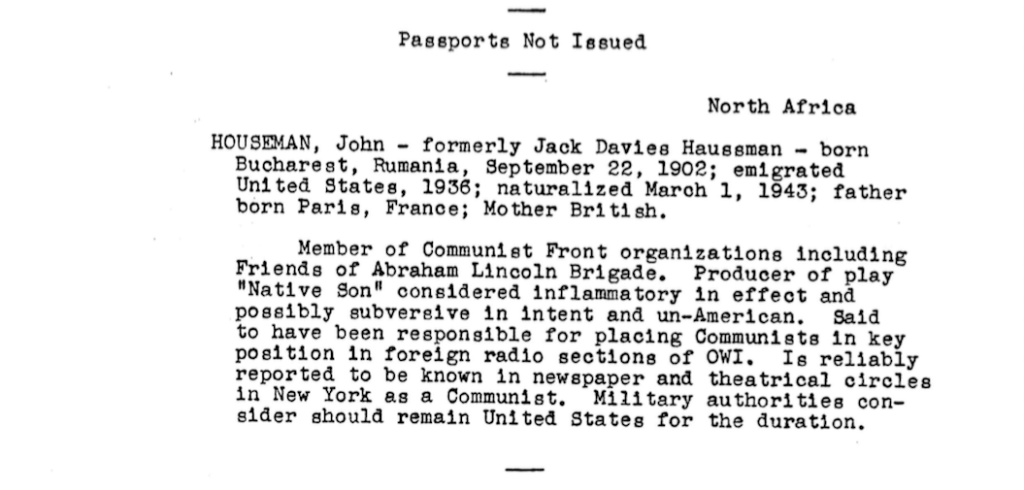

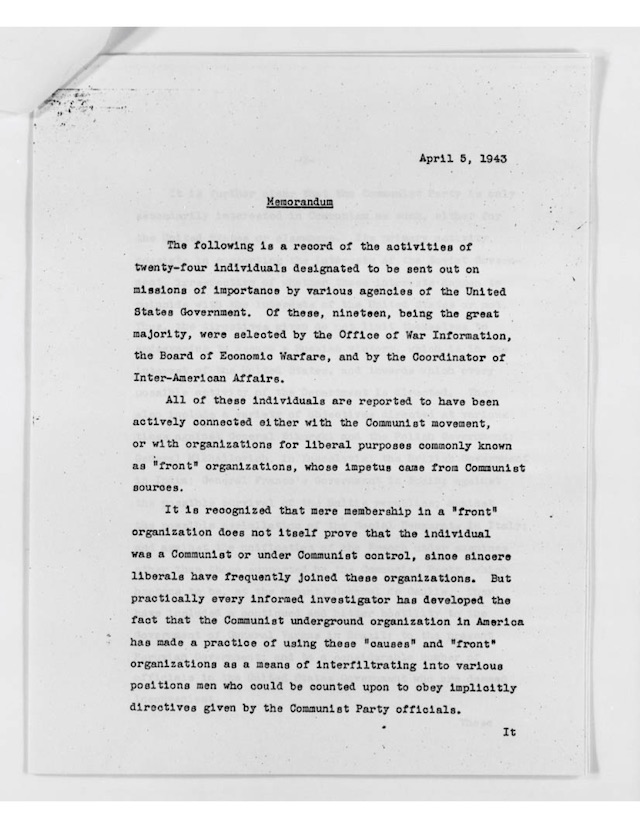

Charles Thayer was hardly the first high-level Voice of America official duped by Soviet propaganda. Government executives in charge of the Voice of America during World War II, including the first VOA director John Houseman, the head of the Office of War Information, radio broadcaster Elmer Davis, and his deputies Robert E. Sherwood and Wallace Carroll–all of them bought into the Soviet Katyn propaganda lie.

Elmer Davis was a journalist before his government service–a well-known New York Times reporter and CBS News commentator. He presented himself later as a fighter for honest journalism, but that is not how a bipartisan congressional committee saw him in 1952 based on his performance from 1942 to 1945 as the director of the Office of War Information.

“Mr. Davis, therefore, bears the responsibility for accepting the Soviet propaganda version of the Katyn massacre without full investigation. A very simple check with either Army Intelligence (G- 2) or the State Department would have revealed that the Katyn massacre issue was extremely controversial.”[ref]The Katyn Forest Massacre. Final Report of the Select Committee to Conduct an Investigation of the Facts, Evidence and Circumstances of the Katyn Forest Massacre pursuant to H. Res. 390 and H. Res. 539, Eighty-Second Congress, a resolution to authorize the investigation of the mass murder of Polish officers in the Katyn Forest near Smolensk, Russia, (Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1952), accessed October 26, 2017, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=osu.32435078695582.[/ref]

Cold War Radio Museum Video

Elmer Davis’ Voice of America overseas broadcasts and a U.S. domestic radio networks broadcast between April 30 and May 3, 1943 (May 3rd also happened to be Poland’s national holiday in commemoration of the May 3rd Constitution) were callous in their lack of empathy for thousands of victims and their families. They included a number of false or misleading assertions included in his earlier VOA commentaries and repeated to Americans in a nationwide radio broadcast. One of his false claims was that medical experts would not have been able to tell how long ago the men were executed.

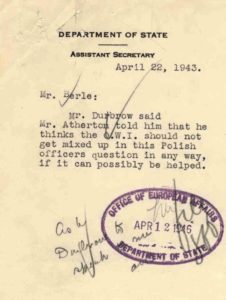

Despite journalistic experience as a New York Times reporter and editorial writer and later a CBS radio news analyst, Davis ignored warnings from various sources about the nature of the Soviet regime under Stalin, including multiple warnings from Jan Ciechanowski, the ambassador in Washington of the Polish government in exile in London. He also ignored advice on Katyn from the State Department, although he later claimed not to remember receiving any guidance. The chances of that being true were minimal. A previously classified note from the State Department, dated April 22, 1943, was a typical low-key recommendation written in diplomatic language which suggested that senior U.S. diplomats most likely told OWI and VOA officials to refrain from accepting and promoting the Soviet explanation for the Katyn massacre. Davis and other pro-Soviet OWI executives and VOA managers and broadcasters simply ignored such warnings.

READ: Polish Ambassador’s Fight With Pro-Stalin Voice of America and Soviet Propaganda in the U.S.

Mr. Berle:

Mr. [Elbridge] Dubrow said Mr. [Ray] Atherton told him that he thinks the O.W. I. should not get mixed up in this Polish officers question in any way, if it can possibly be helped.

Elbridge Dubrow and Ray Atherton were high-level State Department officials responsible for European affairs. Adolf Berle was the Assistant Secretary of State. The State Department was by then aware that the OWI Director Elmer Davis and the Voice of America leadership were already fully engaged in blaming the Katyn massacre on Nazi Germany in domestic radio broadcasts in the United States as well as in overseas VOA broadcasts. If anything, State Department diplomats were trying to tell VOA journalists to practice some journalistic caution, but the pro-Soviet ideologues would not heed their advice. They were followers of the type of pro-Soviet propaganda promoted in the United States by the Anglo-American New York Times correspondent in Soviet Russia Walter Duranty, who in 1932 received the Pulitzer Prize. Duranty was a denier of Bolshevik-caused widespread famine in the USSR with millions of victims, particularly in Ukraine.

Soviet propaganda was eagerly promoted at the Voice of America in 1943 by VOA’s chief news writer and editor Howard Fast, a bestselling author who later joined the Communist Party USA, worked for its newspaper, The Daily Worker, and received the 1953 Stalin Peace Prize.

The truth about the Soviet Union, including any accusations that the Soviet Union was responsible for the Katyn murder, amounted to anti-Soviet propaganda for VOA’s chief news writer and editor in 1943.

As for myself, during all my tenure there [VOA] I refused to go into anti-Soviet or anti-Communist propaganda.[ref]Howard Fast, Being Red (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1990), 23.[/ref]

I established contact at the Soviet embassy with people who spoke English and were willing to feed me important bits and pieces from their side of the wire. [ref]Howard Fast, Being Red (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1990), 18-19.[/ref]

For a journalist, Howard Fast was supremely naive. In a 1998 radio interview, he described how staff members of the Communist Daily Worker, where he had worked after leaving the Voice of America, cried when they read Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev’s 1956 speech about Stalin’s crimes:

And we heard this speech, and many of us wept. Because we did not know, and would not believe, the truth about the Soviet Union. We had erected a Socialist state to our beliefs and to our dreams, and this for us was the Soviet Union.[ref]Pacifica Radio’s Democracy Now, April 8, 1998, “Interview with Howard Fast,” https://www.trussel.com/hf/democnow.htm.[/ref]

READ: Howard Fast – Voice of America’s Only Stalin Peace Prize Recipient

Wallace Carroll, another gullible journalist among VOA’s “founding fathers,” was a newspaper correspondent in the Soviet Union in 1941. His reports from Russia were filled with naive and uncritical acceptance of Soviet propaganda. After the war, Carroll was executive editor of the Winston-Salem Journal and Sentinel, served as news editor in the Washington bureau of the New York Times from 1955 to 1963, and was a member of the Pulitzer Prize Board, still insisted in his book Persuade or Perish published almost three years after the war that the Soviet version of the Katyn massacre was true. He wrote in 1948:

As Hottelet [Carroll’s trusted advisor at OWI Richard C. Hottelet] had predicted, the dissension which was permitted to arise over the Katyn massacre was still working to the advantage of defeated Germany after the war. In July, 1946, more than three years after Goebbels opened his campaign, the German leaders on trial for war crimes at Nuremberg revived the allegations against the Russians in an obvious attempt to drive a wedge between the Soviets and the Western Powers.

Wallace Carroll, Persuade or Perish (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1948), p. 152.

As Hottelet [Carroll’s trusted advisor at OWI Richard C. Hottelet] had predicted, the dissension which was permitted to arise over the Katyn massacre was still working to the advantage of defeated Germany after the war. In July, 1946, more than three years after Goebbels opened his campaign, the German leaders on trial for war crimes at Nuremberg revived the allegations against the Russians in an obvious attempt to drive a wedge between the Soviets and the Western Powers.[ref] Wallace Carroll, Persuade or Perish (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1948), 152.[/ref]

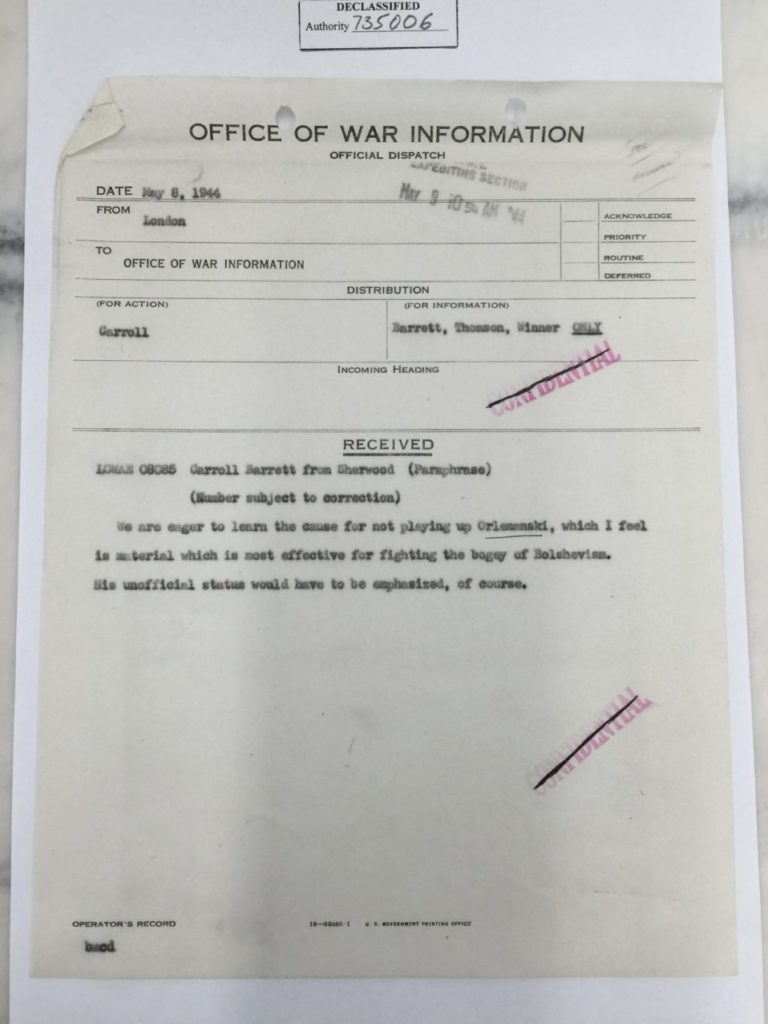

In his book, Carroll repeatedly refers to any warnings about Stalin, communism, the Soviet Union, and Katyn as “the Bolshevik Bogy,” as did Robert E. Sherwood during World War II in a confidential telegram from London to Wallace Carroll. Robert E. Sherwood, in addition to being in charge of Voice of America broadcasts in the Office of War Information, was President Roosevelt’s speechwriter. As the head of all overseas media operations run by OWI, Sherwood issued directives to VOA journalists to support Soviet claims of innocence for the Katyn Massacre and promoted the Soviet propaganda theme that Stalin was no longer an enemy of religion.

According to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the World War II Supreme Commander, communist-inspired excesses by early VOA broadcasters threatened the safety of U.S. troops when Voice of America programs ridiculed tactical agreements reached by him with some of the Vichy France and Italian leaders to lure them out of their former cooperation with Nazi Germany. President Eisenhower noted in his memoir published in 1965 that President Roosevelt put a stop to VOA’s “insubordination.”[ref]Dwight D. Eisenhower, The White House Years: Waging Peace 1956-1961 (Garden City: Doubleday & Company, 1965) 279.[/ref] Of all the post-war U.S. presidents, Eisenhower was least enthusiastic about the Voice of America and was actively involved in the creation of more hard-hitting Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty.

Even in 1948, Wallace Carroll, a celebrated American journalist, was still unwilling to give up on Stalin’s Katyn propaganda lie. He was also plainly wrong in his claim that the Germans had revived the Katyn allegations at the Nuremberg trials of Nazi leaders. Even a basic check of facts before publishing his authoritative book on propaganda in 1948 would have revealed that it was the Soviet prosecutor at Nuremberg who had introduced the Katyn charges and tried to blame the mass murder on the Germans. The Soviets fell into their own trap. It soon became obvious that they could not prove their case with their own poorly fabricated evidence because the crime was, in fact, committed by the Soviet secret police on the orders of Stalin. Seeing his evidence refuted, the Soviet prosecutor quietly dropped the Katyn charges against the German defendants.

In 1942, Carroll published a book devoted entirely to advocating for a close U.S.-Soviet relationship. Titled, We’re In This With Russia, it presented the Soviet Union as a nation transformed by socialism, and Soviet communists as progressive leaders, deserving of America’s support and friendship. While cheering for the joint Soviet-American effort to beat Hitler made perfect sense, Carroll was also particularly concerned that Joseph Stalin still did not have a good press image in the United States. In the Office of War Information, he made sure that the Soviet dictator was presented as a supporter of democracy and progress, despite all evidence to the contrary.

This unwillingness to make intelligent use of the “capitalist press” was only one of a number of weaknesses in the Soviet propaganda organization.

Wallace Carroll, We’re In This With Russia (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1942), p. 89.

This unwillingness to make intelligent use of the “capitalist press” was only one of a number of weaknesses in the Soviet propaganda organization. After all the commotion which has been made about Russian propaganda, I was surprised to find that the Soviets were overlooking many ways of influencing world opinion, not only through the press, but through the movies, the radio, and other media. They seldom missed a trick in the propaganda directed at their own people, but the machinery they employed to put their case before the world would have been considered inadequate by any other great power.[ref]Wallace Carroll, We’re In This With Russia (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1942), p. 89.[/ref]

Wallace Carroll, We’re In This With Russia (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1942), p. 89.

As the head of the OWI London office, Carroll advocated for close coordination of American and Soviet propaganda. He resigned at the end of 1943 when the OWI leadership in Washington did not agree with some of his proposals, but he returned to the agency in 1944 as deputy director for Europe in charge of Voice of America broadcasts.

Alan Heil, a former Voice of America journalist and senior manager who described VOA’s early years in his book, Voice of America: A History, noted that Wallace Carroll became a key member of the new VOA leadership team in 1944.[ref]Alan L. Heil, Jr., Voice of America: A History (New York: Columbia University Press: 2003), p. 44.[/ref]

Heil’s book does not mention Carroll’s pro-Russia advocacy. There are no references in other books and articles about the Voice of America to Howard Fast’s role as the head of VOA news programs and his Stalin Peace Prize. John Houseman’s forced resignation has likewise been ignored in books and articles about VOA.

Wallace Carroll, was one of several “founding fathers” of the Voice of America who were woefully unaware of how cleverly the Soviets manipulated him and such VOA fellow traveler newsmen as Howard Fast. The 1953 Stalin Peace Prize for Fast had to be, in the eyes of the Kremlin, a fully deserved reward for years of supporting such Soviet goals as the establishment of pro-Moscow communist regimes in East-Central Europe. The Voice of America did not cause the Soviet domination over the region, but its pro-Soviet propaganda made it easier for the Kremlin to carry out its disinformation campaign. During the Cold War, VOA under new leadership and with a new staff of refugee journalists contributed to the fall of communism, although not nearly as much as Radio Free Europe.

When Wallace Carroll, the American journalist who helped to create VOA, published in 1942 his book in praise of the Soviet Union, Stalin, and other Soviet communists were already responsible for the deaths of millions of innocent people. Most of them were Russians and Ukrainians, but the victims also included Crimean Tatars, Belorussians, Poles, Jews, Lithuanians, Latvians, Estonians, and many other nationalities and groups. Among millions of men, women, and children who were deported to the Gulag slave labor camps, many quickly died. If they managed to survive, they often never returned to their former homes and became refugees.

Whether through professionally inexcusable ignorance or ideological zealotry, Office of War Information director Elmer Davis and his deputies and key managers–Robert E. Sherwood, Wallace Carroll, Joseph Barnes, John Houseman, Howard Fast, and other Voice of America pioneers, urged VOA listeners to trust Stalin.

After the war, Carroll was an executive editor of the Winston-Salem Journal and Sentinel, served as a news editor in the Washington bureau of the New York Times from 1955 to 1963, and was a member of the Pulitzer Prize Board. In his book Persuade or Perish, almost three years after the war, he still insisted that the Soviet version of the Katyn massacre was true. He also looked down on refugee Voice of America broadcasters if they happened to disagree with him.

“There was another fault of American propaganda from New York [Voice of America broadcast from New York until 1954] that we strove to overcome with just as little success—a fault that can only be described as the émigré imprint.”

Wallace Carroll, Persuade or Perish (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1948), pp. 132-133.

There was another fault of American propaganda from New York [Voice of America broadcast from New York until 1954] that we strove to overcome with just as little success—a fault that can only be described as the émigré imprint. The Office of War Information, like the British propaganda agencies, had been quick to hire talented refugees from the lands overrun by Hitler and Mussolini. These exiles brought with them priceless gifts—linguistic skill, knowledge of national characteristics and customs, journalistic training. I came to know many of them and found them animated for the most part by a sincere desire to carry out the propaganda program of the United States government. But unfortunately, some of them had brought with them passions and political convictions which sometimes proved too much for their good intentions. There were indeed times when they used the American radio to wage polemical battles in which the United States had no interest.[ref]Wallace Carroll, Persuade or Perish (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1948), pp. 132-133.[/ref]

Wallace Carroll, Persuade or Perish (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1948), pp. 132-133.

State Department diplomat Chester H. Opal made a comment in his 1951 confidential memorandum that VOA censorship of Katyn massacre news reports continued after the end of World War II:

“Further, I have the distinct impression that when the Voice of America presented a series on Mikolajczyk’s [Prime Minister of the wartime Polish Government in Exile in London] The Rape of Poland, the one chapter that was omitted — and deliberately — was the one on Katyn.”[ref]January 25, 1951 memorandum from Chester H. Opal to Mr. Schwinn. Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, 1763 – 2002. Series:Central Decimal Files, 1910 – 1963. File Unit: [648.6126/8-2950 – 648.6126/2-2952. Item: Letter from Mrs. James F. Connors Regarding the Voice of America Broadcast on the Katyn Forest Massacre and Related Documents, 12/12/1950. National Archives at College Park, 8601 Adelphi Road, College Park, MD 20740-6001. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/6850483.[/ref]

This was yet another evidence of VOA’s censorship of the Katyn story in the 1940s. In his book published in the United State in 1948, Mikołajczyk was highly critical of wartime Voice of America broadcasts in the Office of War Information. It is more than likely that segment was also omitted by VOA as part of the early post-war VOA censorship and coverup of topics likely to offend the Kremlin and the communist regime in Poland.

Mikołajczyk wrote:

“We finally protested to the United States State Department about the tone of OWI broadcasts to Poland. Such broadcasts, which we carefully monitored in London, might well have emanated from Moscow itself.”[ref]Stanisław Mikołajczyk, The Rape of Poland: Pattern of Soviet Aggression (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1948). 25.[/ref]

The Poles listening during the war to Polish-language radio broadcasts produced by the U.S. government found them to be naive and reflecting Soviet propaganda. Czesław Straszewicz, a Polish journalist based in London, did not have a very high opinion of VOA’s wartime broadcasts to Poland, “whatever name they had then.” “Voice of America” did not become the official and consistently used name until a few years later.

With genuine horror we listened to what the Polish language programs of the Voice of America (or whatever name they had then), in which in line with what [the Soviet news agency] TASS was communicating, the Warsaw Uprising was being completely ignored.[ref]Czesław Straszewicz, “O Świcie,” Kultura, October, 1953, 61-62. I am indebted to Polish historian of the Voice of America’s Polish Service Jarosław Jędrzejczak for finding this reference to VOA’s wartime role.[/ref]

“I mentioned also the tone of OWI broadcasts to Poland. They had been following the Communist line consistently, which made our own job more difficult.”[ref]Mikolajczyk, The Rape of Poland,” 58.[/ref]

The 1951 formerly classified State Department memorandum also includes an additional handwritten comment on how U.S. diplomats feared the power of U.S. public opinion because it could interfere with their diplomatic activities vis-a-vis the Soviets:

“Walter, I keep thinking that if American Polonia [Polish Americans] ever got the idea that the U.S. government is certain of Russian guilt [for the Katyn massacre], a great uproar would result and people would start demanding that Sec. Acheson take the matter into the UN.”

[ref]January 25, 1951 memorandum from Chester H. Opal to Mr. Schwinn. Item: Letter from Mrs. James F. Connors Regarding the Voice of America Broadcast on the Katyn Forest Massacre and Related Documents, 12/12/1950. National Archives at College Park, 8601 Adelphi Road, College Park, MD 20740-6001. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/6850483.[/ref]

“You know the Poles…even American Poles,” a State Department diplomat who wrote the note also observed.

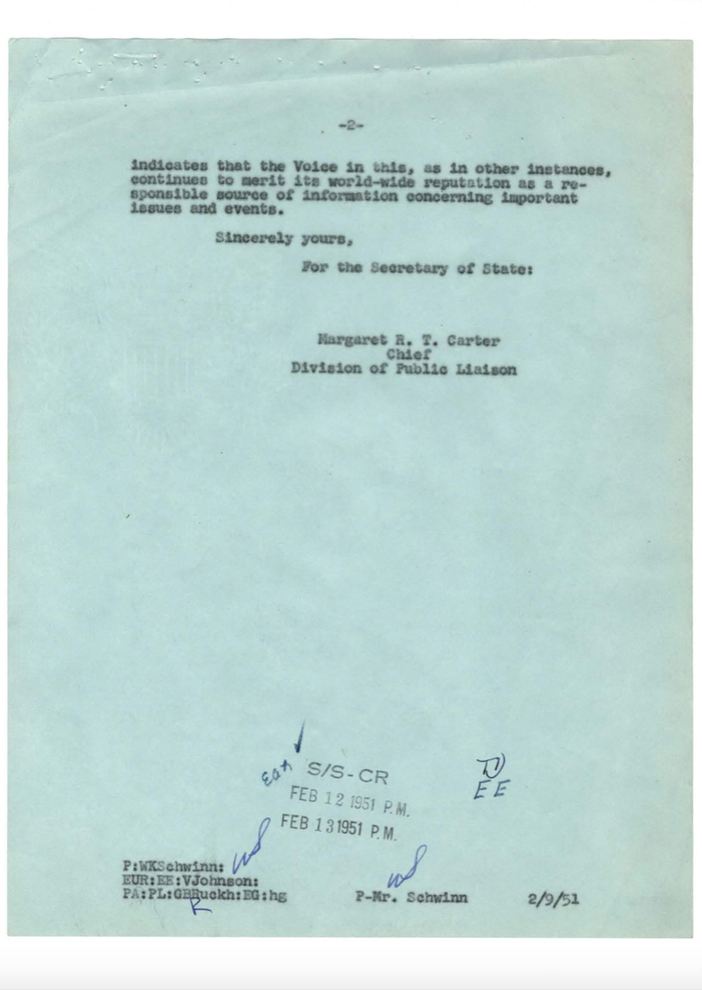

The purpose of the memo was to help draft a response to a concerned American citizen, Mrs. James F. Connors of Holyoke, Massachusetts, who had inquired about Voice of America’s coverage of the Katyn massacre. The Voice of America and the State Department wanted her to believe that “Contrary to the impression you have been given, the Voice of America has on many occasions broadcast to other countries, and especially to Poland, news concerning the massacre at Katyn.”[ref]Copy of the letter from Margaret R.T. Carter to Mrs. James F. Connors. Item: Letter from Mrs. James F. Connors Regarding the Voice of America Broadcast on the Katyn Forest Massacre and Related Documents, 12/12/1950. National Archives at College Park, 8601 Adelphi Road, College Park, MD 20740-6001. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/6850483.[/ref]

The Chief of Public Liaison for the Secretary of State gave examples of a few Katyn-related reports, listed for her by the Chief of the VOA Polish Desk, and urged her to conclude that the Voice of America was doing an excellent job of informing radio listeners abroad:

“I believe you will agree that the above record of the Voice of America broadcasts regarding the Katyn massacre indicates that the Voice in this, as in other instances, continues to merit its world-wide reputation as a responsible source of information concerning important issues and events.”[ref]Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, 1763 – 2002. Series:Central Decimal Files, 1910 – 1963. File Unit: [648.6126/8-2950 – 648.6126/2-2952. Item: Letter from Mrs. James F. Connors Regarding the Voice of America Broadcast on the Katyn Forest Massacre and Related Documents, 12/12/1950. National Archives at College Park, 8601 Adelphi Road, College Park, MD 20740-6001. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/6850483.[/ref]

The statement gave the impression of extensive coverage by VOA when in fact until sometime later it was rare and almost always minimal.

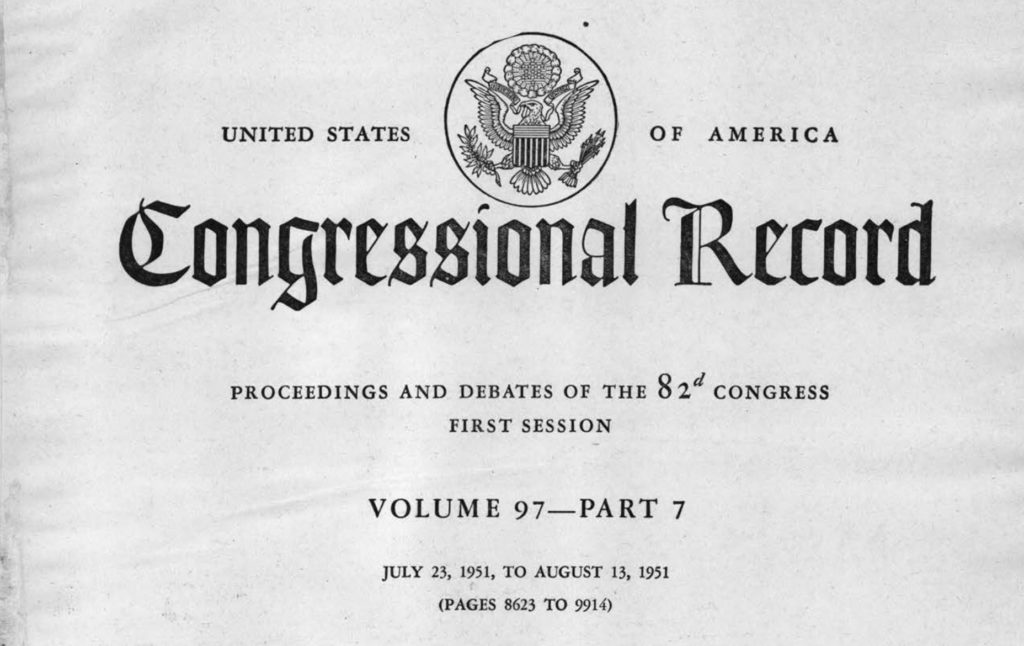

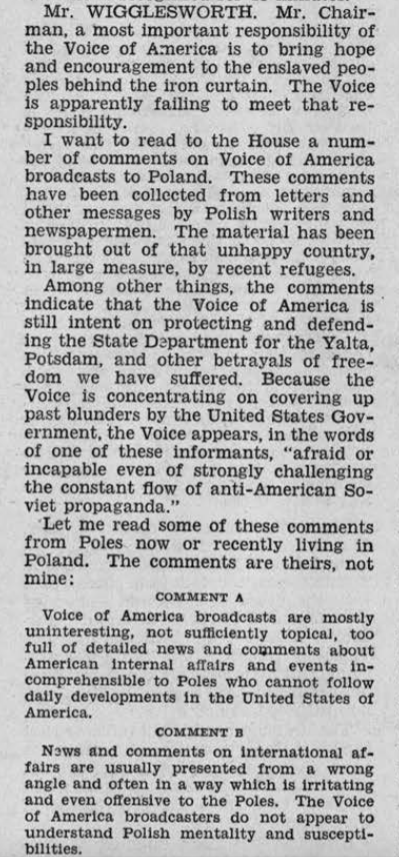

Radio listeners in Poland agreed with the American critics of the Voice of America and offered their own, even more devastating assessments of VOA broadcasts. Speaking to the House of Representatives on July 24, 1951, Congressman Richard B. Wigglesworth (R-MA) read highly critical comments on VOA broadcasts to Poland, which, he said, had been “collected from letters and other messages by Polish writers and newspapermen” and brought to the United States by recent refugees. They described VOA programs as:

“uninteresting, drab, bureaucratic in tone, unconvincing [Emphasis added].”[ref]97 Cong. Rec. (Bound) – Volume 97, Part 7, July 24, 1951; 8749-8750. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1951-pt7/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1951-pt7-2-2.pdf. Also see: Cold War Radio Museum, “Voice of America 1951 – ‘Drab’ ‘Unconvincing’,” February 24, 2018, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/2018/02/23/voice-of-america-1951-drab-and-unconvincing-rep.-wiggleswoth-quotes-listeners-in-poland/.[/ref]

One of the many critical comments from VOA listeners in Poland in 1951 was:

“They give the impression that they are prepared and spoken by clerks who do their job perfunctorily without any intelligent understanding of the human element or of Polish susceptibilities.” [Emphasis added.][ref]97 Cong. Rec. (Bound) – Volume 97, Part 7, July 24, 1951; 8749-8750. Also see: Cold War Radio Museum, “Voice of America 1951 – ‘Drab’ ‘Unconvincing’,” February 24, 2018, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/2018/02/23/voice-of-america-1951-drab-and-unconvincing-rep.-wiggleswoth-quotes-listeners-in-poland/.[/ref]

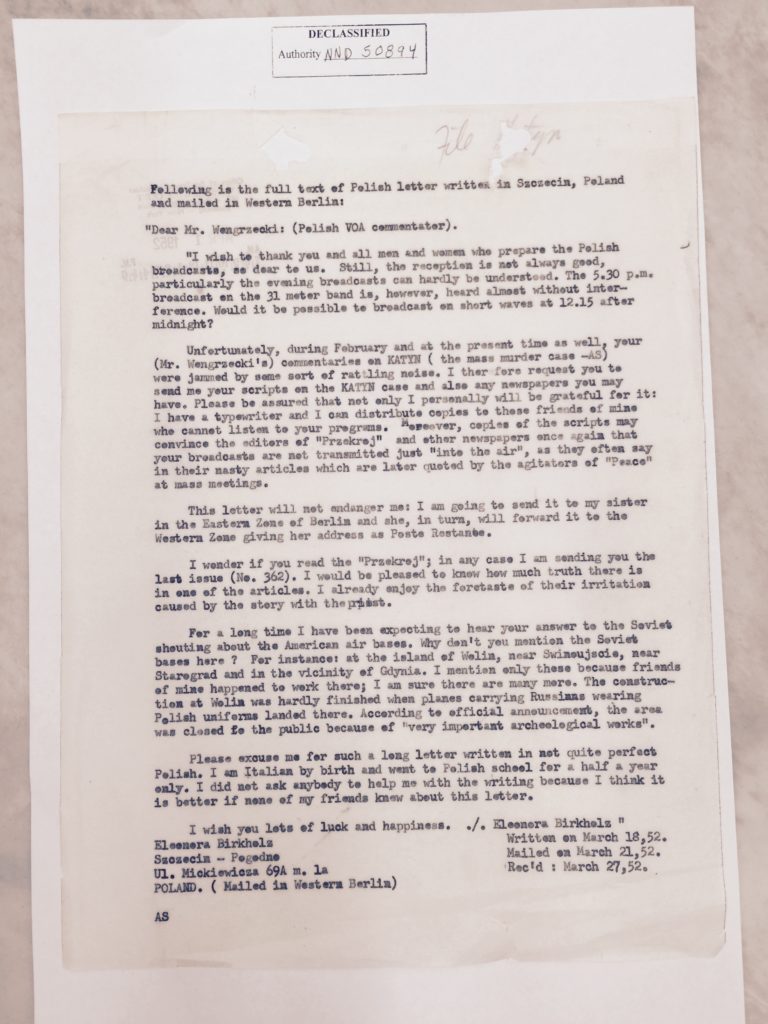

But even VOA’s minimal and censored reporting on Soviet atrocities until 1951-1952 was better for desperate listeners in Poland than no reporting at all, or outright Soviet lies repeated by VOA during World War II. Some listeners in Poland wrote to VOA to express their gratitude for any news about the Katyn massacre. VOA officials used one such letter as proof that VOA’s coverage was more than adequate.[ref]Translation of Letter from Eleonora Birkholtz in Szczecin Poland, to Voice of America Polish commentator Mr. Wengrzecki, March 18, 1952; RG 0059, Department of State, U.S. International Information Administration/International Broadcasting; Entry# P 315: Voice of America (VOA) Historical Files: 1946-1953; Reports – Psychological Operations POC THRU Katyn Forest Massacres III; Container # 18; ARC# 5635478. National Archives at College Park, 8601 Adelphi Road, College Park, MD 20740-6001.[/ref] The letter was sent from Poland in March 1952, but by then the management of the Voice of America had already drastically changed its earlier restrictive programming policy directives and expanded coverage of Katyn-related news and commentaries.

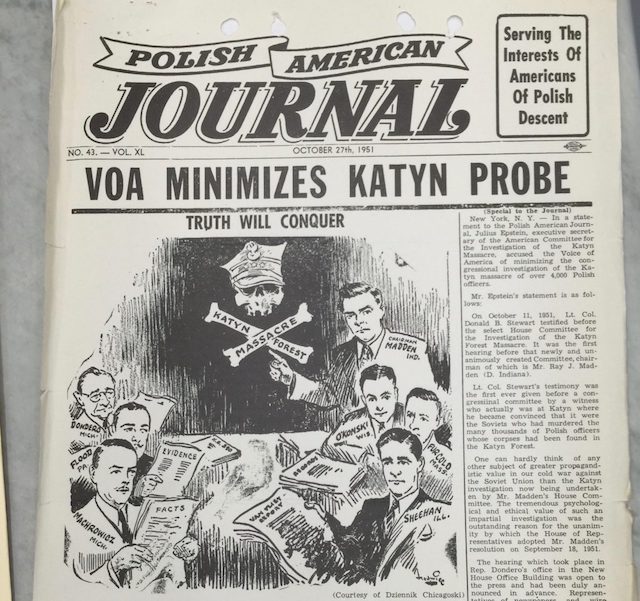

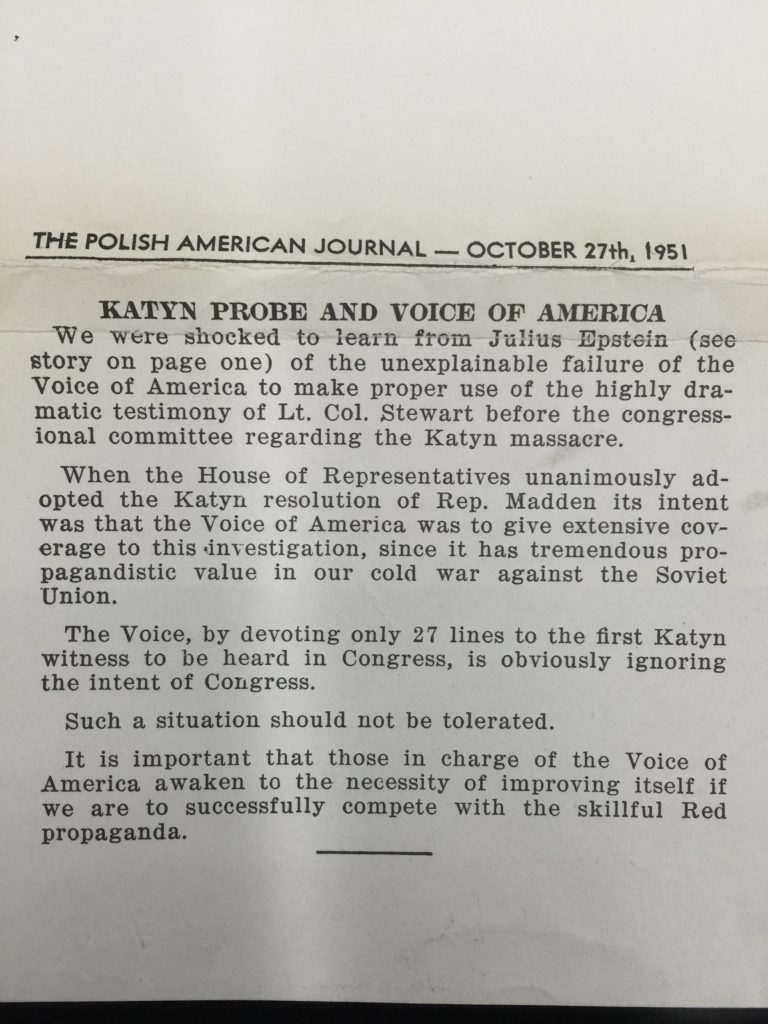

Despite assertions to the contrary from Voice of America officials, even as late as 1951, VOA still avoided the topic and provided only limited coverage of the initial stages of the congressional investigation of the Katyn murders. On October 27, 1951, the Polish-American Journal published an editorial, “KATYN PROBE AND VOICE OF AMERICA.”

We were shocked to learn from Julius Epstein (see story on page one) of the unexplainable failure of the Voice of America to make proper use of the highly dramatic testimony of Lt. Col. Stewart before the congressional committee regarding the Katyn massacre.

When the House of Representatives unanimously adopted the Katyn resolution of Rep. Madden, its intent was that the Voice of America was to give extensive coverage to this investigation, since it has tremendous propagandistic value in our cold war against the Soviet Union.

The Voice, by devoting only 27 lines to the first Katyn witness to be heard in Congress, is obviously ignoring the intent of Congress.

Such a situation should not be tolerated.

It is important that those in charge of the Voice of America awaken to the necessity of improving itself if we are to successfully compete with the skillful Red propaganda.”

One of the internal memos advised VOA officials to present Julius Epstein as “a disgruntled job-seeker who has proven himself to be an irresponsible promoter, an unscrupulous opportunist and a consistent liar.”[ref]”VOA CRITICS” Memorandum, Voice of America Historical Files 1946-1953 Reports-Psychologial Operations POC THRU Katyn Forest Massacres, RG59-Department of State-Entry#P315, National Archives at College Park, 8601 Adelphi Road, College Park, MD 20740-6001. [/ref]

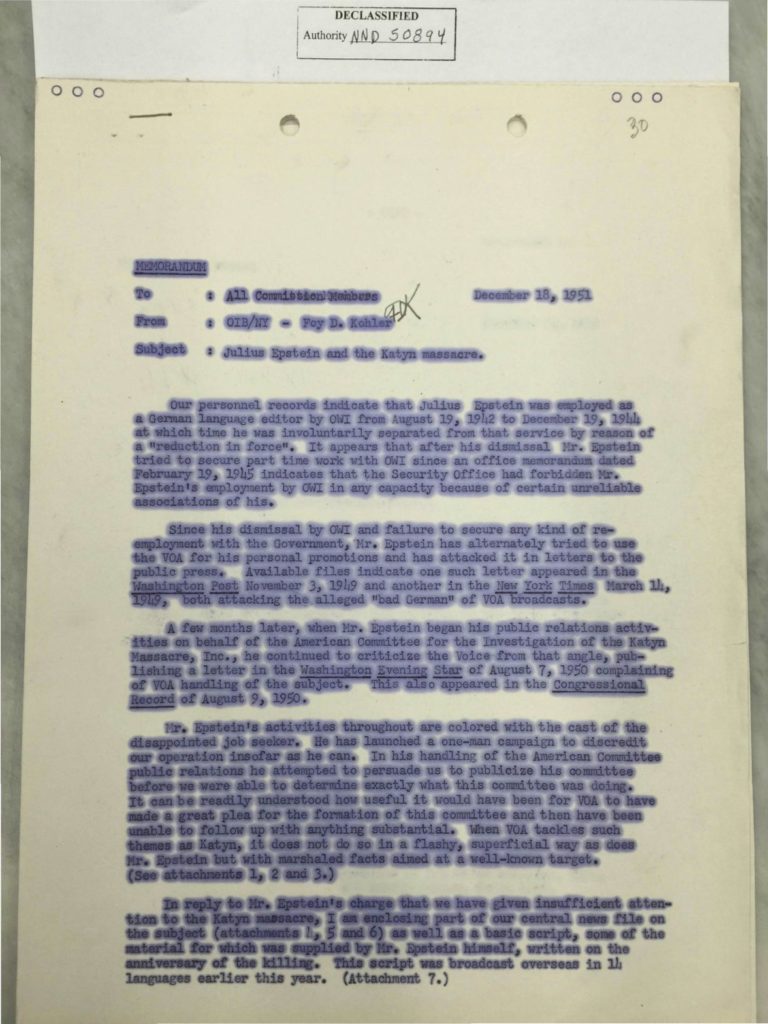

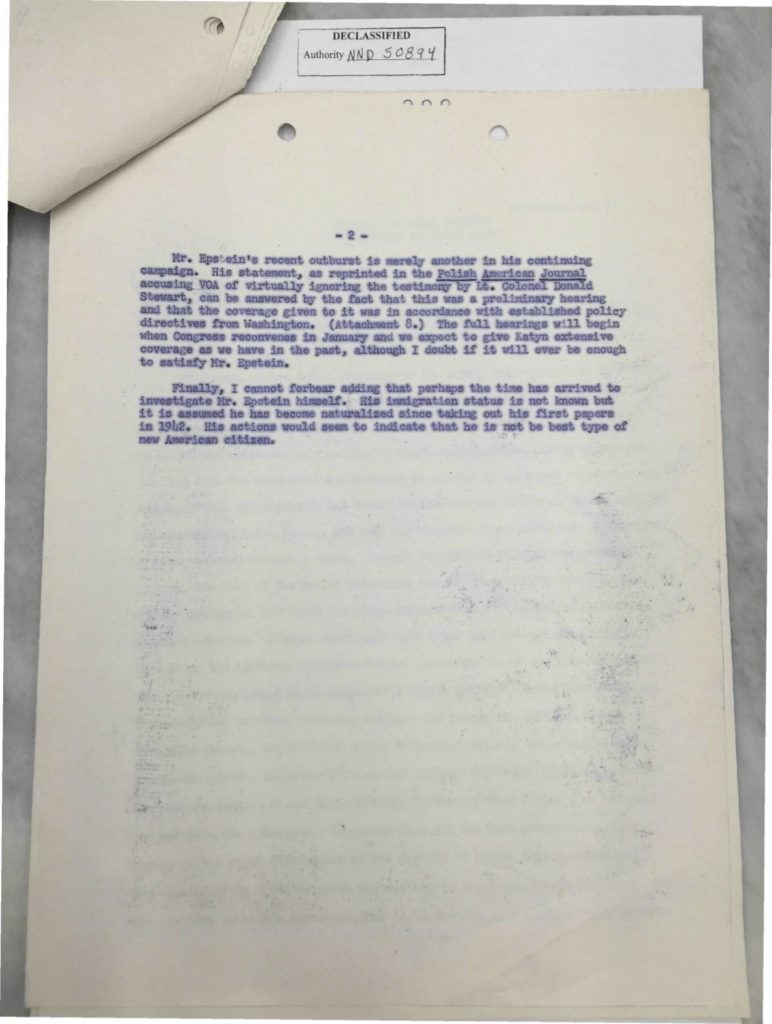

State Department diplomat and Soviet affairs specialist who was Voice of America director at the time (from October 1949 to September 1952), Foy D. Kohler, denied all the charges made by Epstein and proceeded to tarnish his reputation to contacts outside of the U.S. government. In a memo dated December 18, 1951, which was declassified many years later, Kohler wrote that Mr. Epstein’s activities were “colored with the cast of the disappointed job seeker.” In the same memo, Kohler also suggested that Epstein himself should be investigated.

“Finally, I cannot forbear adding that perhaps the time has arrived to investigate Mr.Epstein himself. His immigration status is not known but it is assumed he has become naturalized since taking out his first papers in 1942. His actions would seem to indicate that he is not be [sic] best type of new American citizen.”

Foy David Kohler (February 15, 1908 – December 23, 1990, a career Foreign Service Officer and a specialist in Soviet affairs, found himself under investigation when he and his wife were arrested in December 1952 for drunk driving near Washington shortly after his assignment as the VOA director. At the time of the arrest, he had with him two secret documents in violation of the State Department’s security regulations. The incident did not damage his diplomatic career.[ref]The New York Times, “Inquiry Is Begun on Acheson Aide: Kohler Had 2 Secret Papers When Arrested After Auto Wreck Near Washington,” December 2, 1952, page 18.[/ref] Despite his condescending attitude toward foreigners as demonstrated by his memo, he apparently performed well as an American diplomat in Moscow. After being nominated in 1962 by President Kennedy to be U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union, he served as one of the key liaisons with the Kremlin during the Cuban Missile Crisis and helped in a small way to defuse the threat of a nuclear confrontation, although the key decisions were made at the highest levels at the White House and at the Kremlin.

In response to criticism from Julius Epstein and others, Voice of America officials in the State Department denied that they were censoring the Katyn story. They pointed to what was VOA’s extremely minimal coverage until then as proof that there was no such censorship.

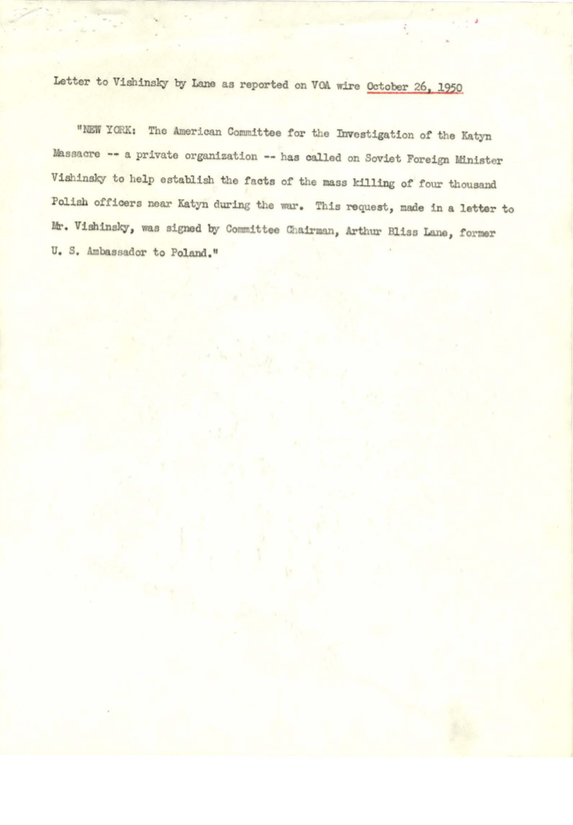

For example, a VOA report on October 26, 1950 about the letter of former U.S. Ambassador to Poland Arthur Bliss Lane to Soviet Foreign Minister Andrey Vyshinsky calling on him to provide information about Katyn had only five and a half lines. This was typical VOA coverage on Katyn in 1949 and 1950 despite tremendous interest in the topic and severe press censorship in Poland, as well as in other countries under Soviet domination, and in Russia itself. Newly-established Radio Free Europe, which had no restrictions on Katyn coverage and much better news service about developments behind the iron curtain, quickly became the most listened to Western radio station in Poland.

In an attempt to hide their censorship, VOA officials also falsely claimed that a Polish officer, an outstanding writer, and artist Józef Czapski, one of the very few survivors of the Katyn murders and the person who had searched for the missing Polish officers in Russia whom Epstein mentioned in the excerpt inserted in the Congressional Record, had voluntarily agreed with the management of the VOA Polish Service to have references to Katyn eliminated from in his 1950 radio talk broadcast by VOA to Poland during his visit in the United States. Czapski was, in fact, pressured by VOA’s management and was outraged by the censorship. Several years later, he wrote about it in a private letter (1959) to Polish-American scholar Prof. J.K. Zawodny whose in-depth study of the Katyn massacre, Death in the Forest, was published by University of Nortre Dame Press in 1962.

Even in the postwar years, after President Roosevelt had died, the war with Japan was over, and the U.N. Charter was already in effect—the policy of suppressing the Katyn case was continued by the State Department. The war was over for several years when Mr. Czapski, the man so activey engaged in searching for the missing men in Russia, and himself a survivor of the annihilation, came to the United States for a visit in the early spring of 1950. The Voice of America invited him to make a broadcast in the Polish language to Poland. From it officials of the Voice of America meticulously eliminated all references to the Katyn Massacre. He was not even allowed to mention the word “Katyn.”[ref]J.K. Zawodny, Death in the Forest (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1972). 186.[/ref]

In a footnote, Prof. Zawodny cited the 1952 Congressional Record and stated that this information was verified by Mr. Czapski in his letter of December 26, 1959.[ref]J.K. Zawodny, Death in the Forest (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1972). 196.[/ref]

Cold War Radio Museum Video

Julius Epstein, a Jewish refugee from Austria who after a brief infatuation with communism in his student years became an anti-communist, was a highly respected freelance journalist and correspondent before the war who reported from Germany on Nazi atrocities for many newspapers and periodicals, among them: Berliner Tageblatt, Hamburger Echo, Neue Zeitung, Leipzig; Prager Tagblatt, Prague; Pariser Tageszeitung, Paris; Revue Internationale de L’Enfant, Geneva; and others. He helped to publicize the censorship of the Katyn story by the Voice of America by bringing it to the attention of American media and members of Congress. Epstein left Germany as a refugee on March 17, 1933, after Hitler’s rise to power, and went to Prague where he worked as a writer and foreign correspondent for Swiss, Swedish, Dutch and French newspapers and periodicals. He also contributed to many democratic and anti-Hitler newspapers and weeklies in Czechoslovakia. In September 1938 during the so-called Munich crisis, he left Prague with his wife and son and went to Switzerland where I obtained an American visa.

On March 9, 1939, he arrived with his family in New York and started to write for the New York progressive weekly The New Leader. He also continued to work as a foreign correspondent for Swiss newspapers.

From March 1942 to December 1944, Epstein worked as Language Editor in the New York offices of the Office of War Information. During that time, he had to wage a continuous struggle against what he described as “the many communists and fellow travelers on the O.W.I.’s pay roll.” He later wrote that “proof of that fight can still be found in the memoranda I wrote while working for the O.W.I.” Part of his duties was to read the Nazi press and to prepare English-language summaries for the use by O.W.I. officials. It was then that he read the report by the twelve international scientists who went to Katyn in 1943 after the Germans discovered the mass graves.

While Voice of America officials continued to attack his credentials and his character, Epstein’s post-OWI journalistic activities eventually led to significant reforms at VOA and the State Department. He and others helped to convince members of Congress to launch in 1951 a bipartisan investigation of the Katyn massacre by a select committee of the House of Representatives. The bipartisan committee concluded in 1952 that the Soviets were without any doubt responsible for the Katyn murders. The congressional committee also revealed that the Voice of America indeed had lied about Katyn during World War II and later “had failed to fully utilize available information concerning the Katyn massacre until the creation of this committee in 1951.” Julius Epstein was proven to be right.

Repeated criticism in Congress from both Republicans and Democrats forced the management of the Voice of America and other officials in the State Department to allow more detailed and more frequent reporting about Katyn. There was a substantially greater number of such VOA reports in 1952 as compared to 1951. Some of the programs in late 1951 and in 1952 also included much stronger criticism of the Soviet Union than in earlier years, but still, none pointed out the complicity of the Roosevelt administration and the Voice of America in the previous cover-up of the evidence of Stalin’s guilt and restricting VOA coverage about Katyn.

In addition to revealing how the United States propaganda outlet broadcast Soviet lies about Katyn without any challenge, the bipartisan congressional investigation also highlighted evidence of illegal censorship of U.S. domestic media during the war by officials who were then in charge of the agency running the Voice of America and their attempts to influence American media and public opinion with false and misleading information about the Soviet Union. One of the OWI officials who tried to censor American media was future U.S. Senator Alan Cranston (D-CA). The so-called Madden Committee, named after its Democratic Chairman, Rep. Ray J. Madden of Indiana, also expressed its bipartisan view that “if the Voice of America is to justify its existence it must utilize material made available more forcefully and effectively.”[ref]”The Katyn Forest Massacre: Final Report.” Select Committee to Conduct Investigation and Study of the Facts, Evidence, and Circumstances of the Katyn Forest Massacre. United States Government Printing Office: 1952, 12.[/ref] The bipartisan committee acknowledged that while there might have been the need out of military necessity not to play up the Soviet responsibility for the Katyn murders when the U.S. and Russia were military allies against Nazi Germany, the blanket censorship of Soviet atrocities by the Roosevelt Administration prevented making better-informed decisions on U.S. policy toward the Soviet Union. The committee also concluded in its 1952 Final Report that there was absolutely no need for such censorship at VOA after the war.

In submitting this final report to the House of Representatives, this committee has come to the conclusion that in those fateful days nearing the end of the Second World War there unfortunately existed in high governmental and military circles a strange psychosis that military necessity required the sacrifice of loyal allies and our own principles in order to keep Soviet Russia from making a separate peace with the Nazis. For reasons less clear to this committee, this psychosis continued even after the conclusion of the war. Most of the witnesses testified that had they known then what they now know about Soviet Russia, they probably would not have pursued the course they did. It is undoubtedly true that hindsight is much easier to follow than foresight, but it is equally true that much of the material which this committee unearthed was or could have been available to those responsible for our foreign policy as early as 1942.

The Madden Committee Katyn hearings and Julius Epstein’s criticism and his public activities resulted later in the 1950s in an increase in VOA coverage of other Soviet violations of human rights. Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty were established in the early 1950s with U.S. government taxpayer money partly to undo the damage of Voice of America’s earlier pro-Soviet propaganda which by withholding the news of Stalin’s atrocities helped him secure control over East-Central Europe.

READ: How a refugee journalist exposed Voice of America censorship of the Katyn Massacre

While RFE and RL never lied about Katyn, the Voice of America, under pressure from public opinion, Congress and Truman Administration White House, and State Department officials eventually dropped its censorship of Soviet and other communist crimes. However, limited censorship of Katyn-related news resumed at the Voice of America at various points in later years of the Cold War, especially during the Nixon-Ford policy of détente toward the Soviet Union. The banning of exiled Soviet dissident writer and Nobel Prize in literature winner Alexandr Solzhenitsyn from participating in Voice of America radio broadcasts to Russia in the 1970s ordered by the station’s own U.S. government management was a shameful and long-lasting episode in the history of otherwise mostly positive contributions of many rank-and-file VOA journalists, even in that period, to the eventual fall of Soviet communist totalitarianism.[ref]Ted Lipien, “SOLZHENITSYN Target of KGB Propaganda and Censorship by Voice of America,” Cold War Radio Museum, November 7, 2017, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/solzhenitsyn-target-of-kgb-propaganda-and-censorship-by-voice-of-america/.[/ref] In the first volume of The Gulag Archipelago 1918-1956: An Experiment in Literary Investigation, Solzhenitsyn wrote about several thousands of Polish officers and members of the intelligentsia who were imprisoned in Katyn and brutally murdered in the spring of 1940 by the NKVD on the orders of Stalin and the Soviet Politburo.

They took those who were too independent, too influential, along with those who were too well-to-do, too intelligent, too noteworthy; they took, particularly, many Poles from former Polish provinces. (It was then that ill-fated Katyn was filled up; and then, too, that in the northern camps they stockpiled fodder for the future army of Sikorski and Anders.) They arrested officers everywhere.[ref]Aleksandr I. Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago 1918-1956: An Experiment in Literary Investigation I-II (New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1974), 77.[/ref]

READ: SOLZHENITSYN Target of KGB Propaganda and Censorship by Voice of America

Extensive passages from The Gulag Archipelago were read in Radio Liberty and Radio Free Europe programs, but the leadership of the Voice of America banned them, possibly to avoid the mention of Katyn and other communist atrocities in order not to annoy the Kremlin and complicate diplomatic relations. Such censorship was eliminated altogether only after personnel and programming reforms were initiated at VOA by the Reagan administration in 1981. These Reagan-era reforms were initially strongly resisted by longtime VOA managers, although many were eventually replaced. Later, some of the managers who were moved into less responsible positions continued to bemoan “the difficult winter of 1981/1982.”

Alan L. Heil, Jr., who had worked for the Voice of America from 1962 until he retired in 1998 and was VOA deputy director for programs, wrote in his Voice of America: A History:

Hollywood’s celebrated film producer John Houseman, who, as head of the overseas radio production section of the Office of War Information, could be considered the first VOA director, came back for its fortieth-anniversary celebration on February 24 [1982]. He reminded the packed auditorium that honest reporting had been the key to the Voice’s credibility when the tide turned in the direction of an Allied victory at the end of World War II. That underlying theme sustained VOA through the difficult winter of 1981/1982.[ref]Alan L. Heil Jr., Voice of America: A History (New York: Columbia University Press Publishers, 2003). 208.[/ref]

It was exactly during World War II when pro-Soviet propagandists working for VOA under Houseman and his immediate successors were most active in defending Stalin, covering up his crimes, ignoring anti-Nazi, anti-communist democratic movements in Eastern Europe, and helping the Soviet dictator impose communist governments in the region. A few Voice of America broadcasters employed by the Office of War Information during World War II and even shortly after the war went to work for communist regimes in East-Central Europe. The head of the VOA Czechoslovak desk, Dr. Adolf Hoffmeister, become the Czechoslovak ambassador to France and VOA Polish desk editor, Artur Salman, aka Stefan Arski, became one of the most virulent anti-U.S. propagandists for the communist regime in Warsaw.

READ: Voice of America Polish Writer Listed As His Job Reference Stalin’s KGB Agent of Influence Who Duped President Roosevelt

READ: First VOA Director was a pro-Soviet Communist sympathizer, State Dept. warned FDR White House

We know of only one Voice of America journalist, Konstanty Broel Plater, who resigned from his job in VOA’s Polish Service in protest against being forced to broadcast Soviet lies about Katyn. The other wartime Polish Service broadcasters promoted the Soviet version of the Katyn story and some of them later worked for the communist regime in Poland.[ref]Ted Lipien, “Hollywood’s Polish Latin lover who terrorized Voice of America broadcasters,” Cold War Radio Museum, September 30, 2019, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/hollywoods-polish-latin-lover-who-terrorized-voice-of-america-broadcasters/.[/ref]