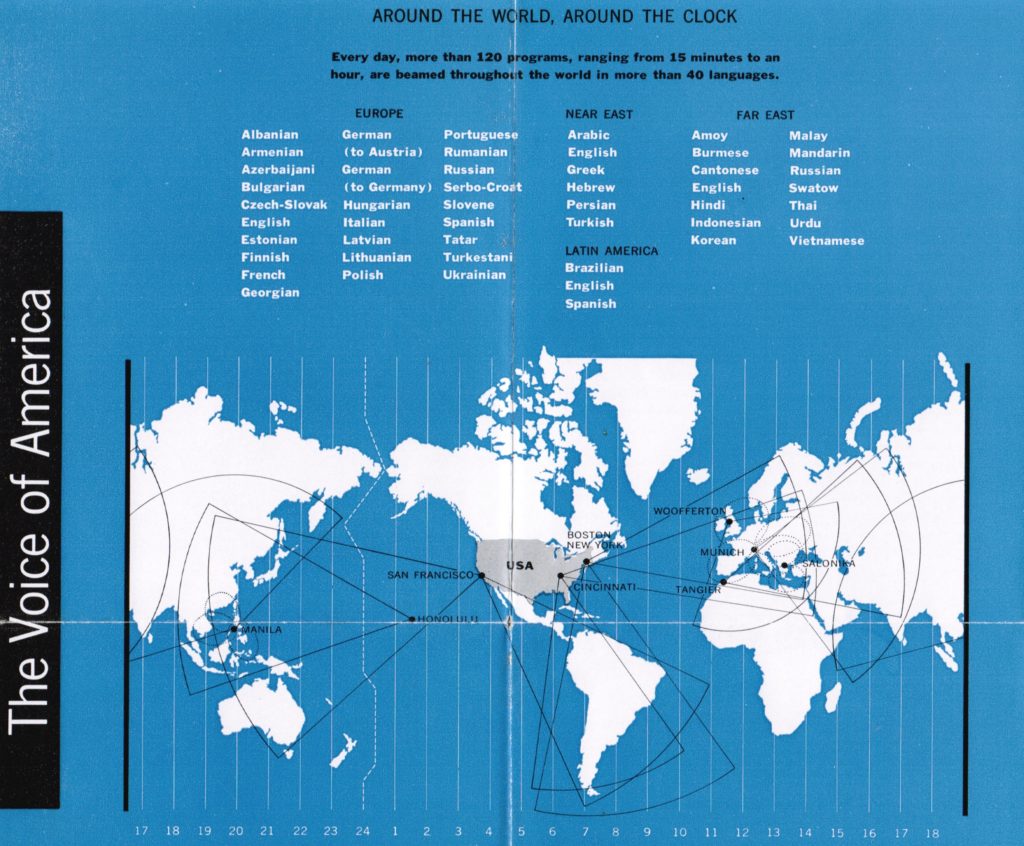

U.S. State Department Describing Voice of America for ‘The Campaign of Truth’ Circa 1952

In the early 1950s, the U.S. State Department launched its public diplomacy program called “The Campaign of Truth” designed to counter Soviet propaganda using the Voice of America (VOA) and the State Department’s public diplomacy programs. They were described in “The Campaign of Truth: How You Can Help” pamphlet, published probably sometime in early 1952. At that time, the Voice of America was operating within the State Department since 1945. Before that, VOA, established in 1942, was part of the Office of War Information (OWI), which President Truman abolished shortly after the end of the war. The launch of “The Campaign of Truth” by the State Department coincided with management and programming reforms designed to make VOA broadcasts more effective against Soviet propaganda.

Prior to about 1950-1951, VOA programs were generally not focusing on the Soviet Union and did not pay much attention to human rights violations in the Soviet Bloc countries. “The Campaign of Truth” represented a radical change from the World War II and the immediate post-war period, when pro-Soviet Voice of America officials and journalists enthusiastically promoted Soviet propaganda and supported Stalin’s plans for establishing communist governments in East-Central Europe. Some of their influence continued until the early 1950s but was rapidly declining compared to what it was during the war.

When the Voice of America started broadcasting, the first permanent VOA chief news writer and editor was Howard Fast, who later joined the Communist Party USA and in 1953 received the Stalin Peace Prize. He resigned from his job at VOA in 1944 and became a reporter and editor for the Communist Party newspaper, The Daily Worker. A few of the wartime VOA broadcasters, among them Stefan Arski (aka Artur Salman), Mira Złotowska Michałowska and Adolf Hoffmeister, went to work for Soviet-dominated communist regimes, and others were slowly replaced in the late 1940s and the early 1950s with anti-communist refugee journalists from Russia and Eastern Europe. One of them was Helen Yakobson who as a young child had left Russia in 1925 with her parents, was educated in China and came to the United States as an immigrant in 1938.

Voice of America programming started to change in the early 1950s, largely in response to heavy bipartisan criticism in the U.S. Congress. Changes in VOA programming were also prompted by the escalation of tensions in relations with Russia and Soviet Bloc countries, the outbreak of the Korean War, and the creation of Radio Free Europe as a competing U.S.-funded radio organization.

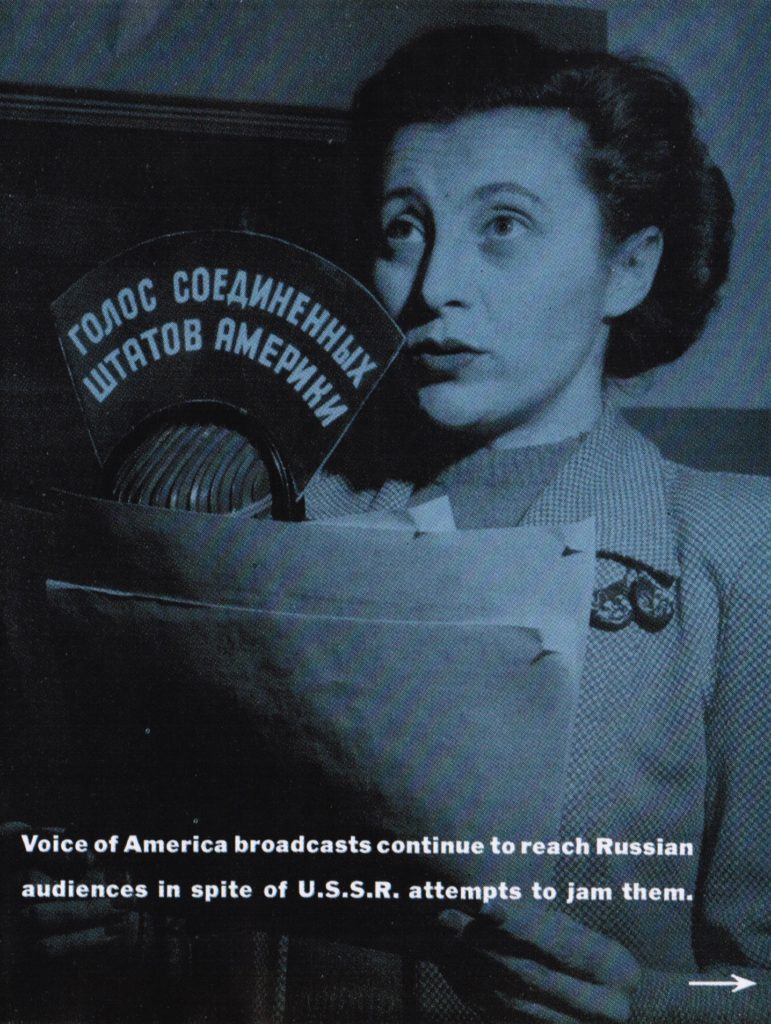

The “Campaign of Truth: How You Can Help” pamphlet included a photograph of a woman radio announcer holding a script in front of the microphone with the Russian sign “Voice of the United States of America.” According to a former Voice of America Russian Service director Marina Oeltjen, the woman in the photograph was Helen Zhemchuzhny Bates Yakobson (1913-2002). Yakobson had joined the Voice of America as it was being reformed and was put to work on the Russian-language program which was launched in 1947, but she was no longer working for VOA when the pamphlet was published by the State Department in 1952 although as a refugee from communism she would have approved of its anti-Stalinist message.

Helen Yakobson was born on May 21, 1913, in St. Petersburg, Russia to a modestly wealthy upper-middle class family. Her father was a physician Alexander Zhemchuzhny and her mother, Zinaida (nee Volkov) had a university degree in biology. After the communist coup in Russia in 1917, Dr. Zhemchuzhny was a minister of health in one of the anti-Bolshevik regional governments and fought in a Cossacks’ cavalry regiment against the communists until the White Russian Army had to surrender to the Red Army. He was lucky that his life was spared because he was a doctor. Several years later while Helen was still a child, the family left Russia for Harbin, Manchuria with the permission of the Soviet authorities after her father was appointed the chief physician of a Soviet-run hospital in the Chinese city. It was a favor to her father from a communist official whom he had treated as a doctor. At that time Harbin had a large number of Soviet officials and employees of the Trans-Siberian railroad, which was operated jointly with China, as well as Russians escaping communist oppression. In 1929, her father resigned from his position at the city hospital and broke his ties with the Soviet authorities. The family joined the ranks of stateless Russian refugees in China, where Helen grew up and shortly before the Japanese occupation of Manchuria enrolled in a local university. After her graduation with a law degree and a move to Tiensin (Tianjin), which had Western colonial enclaves recognized by the Japanese, she started working as a reporter for a Russian-language magazine and had a job teaching Russian language and literature at a Jewish high school. In China, she met and married Abe Bihovsky, a son of an American-Russian-Jewish businessman, and in 1938 emigrated to the United States to join her husband, who later Americanized his last name to Bates. In some documents and articles, her name before her second marriage appears as Elena Bates.

Helen Yakobson had a relatively short career as a journalist and broadcaster with the Voice of America in the 1940s. After a divorce and her marriage in 1950 to Sergei Yakobson, a research scholar at the Library of Congress, she continued in her primary occupation as an educator and became a respected professor of Russian at George Washington University. She died of cardiopulmonary arrest December 4, 2002, in Washington, DC.

In her memoir, Crossing Borders: From Revolutionary Russia to China to America, Yakobson devoted one chapter to the Voice of America and made several observations about leftist and pro-communist views of some of her American friends in the intellectual circles in New York before, during and after World War Two. She noted in her book that as a child, she herself became indoctrinated by communist propaganda in Soviet schools despite her family’s anti-communist background, but as she matured and met émigré Russians, her views changed. She did not comment in her book on pro-Soviet propaganda in early Voice of America radio broadcasts, but she confirmed that even for a few years after the war’s end in 1945, no criticism of the Soviet system was allowed in VOA programming.

In those early years, VOA programs attempted to give full and impartial reports of life in the United States, including confessions of our shortcomings and faults. No direct criticism or attacks on the Soviet system were permitted. After all, they had only recently been our allies. But as the Cold War intensified, VOA responded and became openly and vigorously critical of the Soviet system and government.[ref]Helen Yakobson, Crossing Borders: From Revolutionary Russia to China to America (Tenafly, N.J: Hermitage Publishers, 1994), 146.[/ref]

Yakobson mentions in her book that the Voice of America was developed during World War II in the United States government’s Office of War Information and even quoted Howard Fast without identifying him as an American communist and Stalin supporter or that he was in charge of news at VOA.

Howard Fast, in his memoirs, captured the spirit of its broadcasts to warn-torn Europe most eloquently: “This is the Voice of America; this is the voice of mankind’s hope and salvation, the voice of my wonderful, beautiful country which will put an end to fascism and remake the world…”[ref]Helen Yakobson, Crossing Borders: From Revolutionary Russia to China to America (Tenafly, N.J: Hermitage Publishers, 1994), 143.[/ref]

Howard Fast was one of the prominent figures of the American left, which–as she observed in her book written after the collapse of communism–“was full of hope and had a high sense of mission in fighting for their socialist ideals.”

“Communism became a powerful ideology building upon illusions accumulated over many centuries,” Yakobson wrote. [ref]Helen Yakobson, Crossing Borders: From Revolutionary Russia to China to America (Tenafly, N.J: Hermitage Publishers, 1994), 124.[/ref] Many of the early VOA officials and broadcasters were pro-Soviet fellow travelers; Yakobson joined VOA after some had already left and others were being replaced by anti-communist journalists like herself.

Unlike American-born Howard Fast, Helen Yakobson was one of millions of Russians who had experienced and rejected communism. It was a happy moment for her to see in 1991 the statue of Polish-born communist Felix Dzerzhinsky, founder of the Soviet secret police, “dangling helplessly in the air in front of KGB headquarters, suspended on the ropes of a new revolution.” “In whichever direction this one may go,” she added. [ref]Helen Yakobson, Crossing Borders: From Revolutionary Russia to China to America (Tenafly, N.J: Hermitage Publishers, 1994), 11.[/ref] Current President of Russia Vladimir Putin had a career with the KGB.

A few more details about Helen Yakobson’s life were included in her obituary:

Yakobson graduated with a law degree from the University of Harbin in 1934, but ended up teaching Russian language and literature for two years, before the Japanese invasion of China led her to immigrate to the United States in 1937 [1938 in her memoirs]. During World War II she worked for the Voice of America, and during the late 1940s was a script-writer and announcer for Russian programs for the U.S. Department of State in Washington, D.C. [Her employment with the State Department was to work on Voice of America broadcasts; whether she also had worked for VOA in the Office of War Information (OWI) in some capacity during World War II is not mentioned in her memoir.] In 1951, she joined the faculty at George Washington University, where she was a professor of Russian until she retired in 1983; she was also chair of the Russian Department from 1958 to 1969. Yakobson wrote several Russian textbooks, including A Guide to Conversational Russian (1960) and Conversational Russian: An Intermediate Course (1985), and was also author of the autobiography Crossing Borders: From Revolutionary Russia to China to America (1994).

Former VOA USSR Division Director Mark Pomar noted that “Helen and her parents endured the civil war in Kuban, which was horrific, and then lived in Moscow during the hunger of the early 20s. They made it to Harbin only in 1925.”

According to former VOA Russian Service broadcaster Dr. Irene Kelner, “Yakobson was the head of the Washington chapter of the organization called Russian Litfond. ( Literary Foundation.) It was a club which organized monthly meetings of Russian language writers who read new works and discussed them with other members. They also collected money for the writers in need. Helen Jacobson was also known as a collector of Russian art and had organized several exhibits at her house in Washington, DC.”

She received several awards for her teaching, including a 1995 award from the Russian Embassy for “preservation and development of Russian cultural and spiritual values.”

While her obituary says that during World War II Yakobson worked for the Voice of America, it should be noted that VOA did not start broadcasting in Russian until 1947 because during the war U.S. officials in the Roosevelt Administration apparently feared that launching Russian-language broadcasts might offend Stalin. U.S. government radio broadcasting operations, which later became known as the Voice of America, started in New York in 1942 in the Office of War Information. The first VOA radio program was in German, followed later by programs in other languages, but not in Russian until 1947. In describing the new VOA Russian-language program, Yakobson wrote:

I valued highly their definite anti-communist commitment, and felt certain that this country was indeed “mankind’s hope and salvation.”[ref]Helen Yakobson, Crossing Borders: From Revolutionary Russia to China to America (Tenafly, N.J: Hermitage Publishers, 1994), 143.[/ref]

Living in New York, Yakobson silently despaired pro-communist sympathies among her left-leaning American acquaintances.

“I was surprised to hear,” she wrote, “these Marxist ideological clichés uttered seriously by well-educated Americans.”

It was not only surprising, but sad. They opposed Stalinist Russia, yet they were in favor of socialist experiments. They felt certain that the “mistakes” of the Russian revolution could be avoided and a “true” socialist order established.[ref]Helen Yakobson, Crossing Borders: From Revolutionary Russia to China to America (Tenafly, N.J: Hermitage Publishers, 1994), 124.[/ref]

Before “The Campaign of Truth” transformation of the Voice of America in the early 1950s, initial VOA Russian-language programs to the USSR were not critical of the Soviet government. The early emphasis by VOA’s management in the State Department was on American news and good radio production. Helen Yakobson was trained to be a radio announcer by VOA’s flamboyant producer, Edward Raquello, who concluded that her “good night” closing was not sufficiently “warm and intimate” and advised her that as “a married lady” she should use her seductive “bedroom voice.” She was terribly embarrassed and tried again until finally, he told her to “practice it at home.” Many early female Voice of America broadcasters endured similar indignities from their male colleagues and bosses, at one point her supervisor telling her that she had to resign because he had promised to give her position to his ex-wife who needed a job. Yakobson went to the Personnel Office to complain and kept her position. During her work at VOA, which lasted almost four years, she was assigned to host an American music program on jazz, but the U.S. Embassy in Moscow complained that she was “too serious” for a disk jockey and the management returned her to writing news.[ref]Helen Yakobson, Crossing Borders: From Revolutionary Russia to China to America (Tenafly, N.J: Hermitage Publishers, 1994), 146.[/ref]

The key to modern diplomacy

— people talking to people — is

the principle behind

the world-wide Campaign of

Truth in which the United

States is now engaged. The

most important American

voice heard around the world

today is not that of the

government alone but of

Americans speaking as

individuals or as representa-

tives of industry and labor,

churches and schools —

to millions of workers,

businessmen, churchgoers,

and students the world over.Yet, the government’s part in

the Campaign of Truth

is many-sided. For nearly a

decade, the overseas

information program has

aimed to give the world

a “full and fair” picture of the

U.S. and what it stands for.

Now it has an additional

task — to expose the big lie

of Soviet propagandists and

project clearly the foreign-policy aims of the United States. This it does through

many media — radio, press,

periodicals, motion pictures,

cultural centers, and libraries.Fastest day-to-day medium

for reaching audiences

abroad is the Voice of

America, which surmounts

barriers of distance, censor-

ship, and illiteracy. Now,

some 300,000,000 listeners

have the opportunity to

hear political commentary,

facts about the U.S., round-

table discussions — the

truth they would not know

without the Voice. More than

90,000,000 readers can

learn the latest news through

some 10,000 foreign news-

papers and magazines which

use a daily bulletin of news

sent by wireless

to U.S. diplomatic

missions abroad. Motion

pictures show the life of

American farmers, teachers,

craftsmen; the work of

artists and musicians; big

industry and small business;

community activities — all

these revealing the growth

of the U.S. under freedoms

it has cherished for 175

years. But movies no longer

merely project American

life. A month after South

Korea was invaded, a new

film THE UNITED NATIONS

AIDS KOREA IN HER FIGHT

AGAINST AGGRESSION was

completed in 29 languages.

Within a week, it was

being shown throughout the

world, both in commercial

theaters through the

cooperation of the American

motion picture industry,

and in regular USIE outlets,

including mobile units.The actions of the United

States and the UN have made

possible an effective Campaign of Truth; for the big lie loses ground before the

psychological offensive of

truth in a free world.